What The Industry Is Saying About The EPA Contaminant Candidate List 5

It is assumed that most individuals involved in the advocacy, treatment, and regulation of drinking water in the U.S. have similar opinions on the importance of delivering clean, safe drinking water to the public. But determining how regulatory steps regarding daily practices at water treatment plants (WTPs) should evolve tends to reveal some differences in opinion. While specific impacts on treatment practices and associated costs from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) draft version of the Drinking Water Contaminant Candidate List 5 (CCL 5) remain to be seen, published public comments from industry organizations and individuals represent a wide range of perspectives.

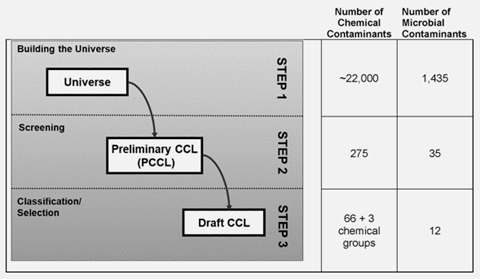

The new CCL 5 draft list comprises 69 chemicals/chemical groups plus 12 microbial candidates (8 bacteria, 3 viruses, and 1 protozoa). New chemical additions since the CCL 4 include 1,2,3-Trichloropropane, Bisphenol A, Boron, diazinon, fipronil, lithium, Tris(2-chloroethyl) phosphate (TCEP), tungsten, multiple disinfection byproducts (DBPs), and multiple per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.* Multiple cyanotoxins remain on the list as well, including, but not limited to: anatoxin-a, cylindrospermopsin, microcystins, and saxitoxin. The new microbial additions since the CCL 4 are Mycobacterium abscessus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The July 9, 2021, draft was whittled down from a list of about 22,000 possibilities in several phases (Figure 1).

The EPA website offers additional background links regarding the CCL 5 specifically and the Contaminant Candidate List and Regulatory Determination in general.

Figure 1. The CCL 5 was developed through a threestep process, which started by listing about 22,000 chemical-contaminant and more than 1,400 microbial-contaminant candidates before refining them down to the final listings.

Responses To The CCL 5 Draft

One of the more common themes referenced throughout the feedback published at the CCL 5 Comments Docket revolves around the topics of PFAS, class-based vs. specific PFAS compounds, and related terminology used in the CCL 5 Draft. Links to the complete, original, response documents are included below for proper context.

- PFAS Specialists. One of the more detailed responses in that area, from David Andrews et al. — reflecting the inputs of 13 scientists with PFAS chemistry and toxicity expertise — addressed the importance of terminology, stating, “EPA employs a ‘working definition’ of PFAS that is inconsistent with the commonly accepted definition recently adopted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (‘OECD’) and used in most U.S. legislation … we urge EPA to instead use the PFAS definition recently adopted by the OECD (‘OECD definition’), which is scientifically sound and consistent with definitions that have been included in federal and state laws regulating PFAS.”

- American Water Works Association (AWWA) outlined eight major points, including:

- “For the CCL to be an effective tool it must be a short, preferably prioritized, list.

- “CCL 5 and subsequent CCLs should be used to inform coordination with other EPA programs (e.g., the Toxic Substances Control Act program) in order to prevent contamination of the nation’s water supply.

- “The CCL process should be an ongoing effort rather than the current prepare-pause-regenerate preparation model and that the ongoing effort should be in concert with external expert input.”

- The Association Of State Drinking Water Administrators (ASDWA) provided comments on several specific contaminants and recommended “that EPA take steps to optimize the connection between the CCL and UCMRs (Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rules). Future UCMRs should be designed to generate robust national occurrence data to fill data gaps for contaminants listed on the most recent CCL.”

- The National Groundwater Association (NGWA) expressed a sense of urgency regarding PFAS monitoring and regulation based on the fact that “When detected, median total PFAS concentrations were higher in small PWSs serving 10,000 or fewer persons than in large PWSs” noting that “75 percent of U.S. community water systems are primarily ground-supplied and 96 percent of those … are small water systems serving 10,000 or fewer people.”

- The Waterkeeper Alliance applauded “EPA’s inclusion of three dangerous chemical groups (cyanotoxins, DBPs, and PFAS),” but noted, “We remain concerned, however, about the slow pace of EPA’s administration of the SDWA over many years with respect to review of unregulated contaminants, determining which contaminants require listing on a CCL for further review, affirmatively determining which contaminants require regulation, and then setting legally enforceable limits for those dangerous contaminants” citing previous efforts that fell behind statutory requirements. The Alliance urged an increase in staff assignments and program resources.

- Silent Spring Institute, an independent research organization, also pushed for better PFAS coverage, stating, “While we commend EPA for listing PFAS as a group in these initial steps toward increased regulation of PFAS in drinking water, the current structural definition of PFAS in the proposed rule is too narrow. Rather than this definition, EPA could include all the PFAS included in its Master List of PFAS, a list which currently contains 9252 chemicals and continues to expand… EPA needs to increase its analytical capacity to regulate PFAS as a class… Because many PFAS are detected outside of those included in EPA’s methods, it makes sense for EPA to develop approved methods that measure total impact from PFAS.

- Advocates And Anonymous Comments. Comments from individuals and non-industry groups ranged from generic comments in favor of drinking water protections to appeals to do more:

- “I was struck that this is required only once every five years and is limited to 30 contaminants and don’t understand why either is in place.”

- “I recommend PFAS be listed as a group, or class, in the final CCL 5, rather than retaining only PFOA and PFOS, which were listed in the Final CCL 4… Regulating individual substances in a group is akin to playing the classic game ‘Whack-A-Mole’.”

- “I support the regulation of the ‘66 individual chemicals, 12 microbes, and three chemical groups — per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), cyanotoxins, and disinfection byproducts (DBPs)’… However, I urge the EPA to add Endocrine Disruptors (EDCs) found in pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) to the list of regulated chemicals… Research shows that EDCs have been proven to undermine the safety of drinking water by affecting development, fertility, and reproductive function.

Not all respondents were in lockstep with the EPA, however. Some offered other perspectives on terminology and research on specific topics of interest:

- Defining Problematic PFAS. One respondent made the point not to tar all polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) fluoropolymers with the same brush. “As a general matter, we support the transition away from PFAS materials, but we believe the definition in this regard must be clear so that it does not include fluoropolymers made without the use of PFAS surfactants. To that end, we propose to modify the draft definition in the NPRM (Notice of Proposed Rulemaking) to the one recently adopted by the state of Delaware: “PFAS means non-polymeric perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances that are a group of man-made chemicals that contain at least 2 fully fluorinated carbon atoms, excluding gases and volatile liquids.” We believe that this definition correctly captures the PFAS chemicals of concern while leaving out fluoropolymers that have completely different properties.”

- Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Assessment. In the conclusion to its submitted comments, the Manganese Interest Group said, “As explained in these comments, the best available science does not support maintaining manganese on the CCL 5. EPA’s chemical contaminants screening process inappropriately relies on the 2019 Health Canada drinking water assessment. Manganese would not have been included on the CCL 5 if EPA’s chemical contaminants screening process had appropriately relied on the best available science, specifically the use of the validated human PBPK model for manganese updated to include a drinking water component. Accordingly, MIG respectfully requests that EPA delete manganese from the CCL 5.”

- The Chloropicrin Manufacturers’ Task Force (CMTF) contends that “EPA’s Office of Pesticide Programs concluded that ‘the concentrations of chloropicrin detected in potable water are below the concentrations of HED’s level of concern” and “Regulation of the contaminant does not present a meaningful opportunity for health risk reduction for persons served by public water systems. Therefore, the criteria for listing are not met.”

- The American Chemistry Council (ACC) “supports the identification of individual per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) that meet the criteria for inclusion on the CCL established by the Agency, but strongly opposes the proposal to include the entire class of PFAS on the CCL 5. The draft proposal and supporting documentation have not provided evidence to support a finding that all PFAS ‘present the greatest public health concern’ related to drinking water exposure.”

What Does All Of This Mean To WTPs?

According to the EPA’s notice of availability and request for comments on the CCL 5 draft, “The Draft Contaminant Candidate List 5 (CCL 5) and the Final CCL 5, when published, will not impose any requirements on regulated entities.” It also states that, “The regulatory determinations process for contaminants on the CCL is a separate agency action.” The EPA defines its next steps, saying, “Between now and the publication of the Final CCL 5, EPA will evaluate comments received during the public comment period for this document, consult with EPA's Science Advisory Board, and prepare the Final CCL 5 considering this input.”

Water Online will address the publication of the Final CCL 5 and any regulatory outcomes once they are formally issued. In the meantime, interested individuals can learn more about regulatory and legislative resources in general, or about PFAS concerns specifically, from the extensive Water Online archives.

* “This group is inclusive of any PFAS (except for PFOA and PFOS). For the purposes of this document, the structural definition of PFAS includes per- and polyfluorinated substances that structurally contain the unit R-(CF2)-C(F)(R’)R’’. Both the CF2 and CF moieties are saturated carbons and none of the R groups (R, R’ or R’’) can be hydrogen.” (As per https://www.epa.gov/ccl/draft-ccl-5-chemicals)