'Buy American' Enforcement: Plugging Leaks

By Mark Gibson

Part 4 of a four-part series, “From Fish To Flint: Four Fixes For EPA’s Water Programs” (Learn more about the series.)

EPA doles $2 billion a year in water grants that are supposed to go to American-made products — but don’t, necessarily. The way EPA leaks funds to foreign firms is like watching lead leach in Flint — it’s absurd and it just keeps flowing. The loopholes to close are explained here. (The Chinese and the multinationals won’t like this.)

The U.S. EPA administers $2 billion a year in water and wastewater grants to help build our infrastructure, on top of their recompense STAG (State and Tribal Assistance Grants) monies. In the first year of the Obama Administration, EPA for the first time instituted Buy American procurement requirements for their State Revolving Fund (SRF) grants. Just as quickly, EPA went to work finding ways to circumvent their Buy America rules.

Depending upon how you count, since 2009 EPA granted about 100 project-specific or blanket waivers to Buy American requirements.1 Poring through the exemptions, we find that about one-fifth were clearly granted because of lack of any U.S. manufacturer. Other exemptions were awarded because utilities or their consulting firms standardized around non-U.S. made goods, or U.S. producers couldn’t meet the short lead times spec’d. Stainless steel nuts and bolts and pig iron products (typically made by the Chinese) enjoy national waivers.

Let’s look at some specific EPA waivers.

Take Ruidosa Downs, a New Mexico village where horse tracks and casinos make the best jobs. The town’s wastewater authority, faced with EPA’s nutrient regulations (again), designed a $36M facility with German and Japanese filtration, paid in part by EPA. The EPA allowed the disqualification of two U.S.-made aeration blowers because they exceeded noise specs by 5 to 9 dB, which “would interfere with the system operators and with occupants of nearby offices”.2 [Note: 10 dB is equivalent to hearing a pin drop.]

Also under EPA’s water office, the town of Falmouth, MA, secured funds and a waiver to purchase a foreign $4.3M wind turbine for its sewer plant. At least one domestic manufacturer could source a turbine, but according to the EPA, “The domestic manufacturer cited the setback distance … as the basis for its refusal to make its product available for this project.”3 U.S. wind turbine makers must back their wares based on U.S. setback standards, based on rules to protect public risks like blade failures, unlike foreign manufacturers.

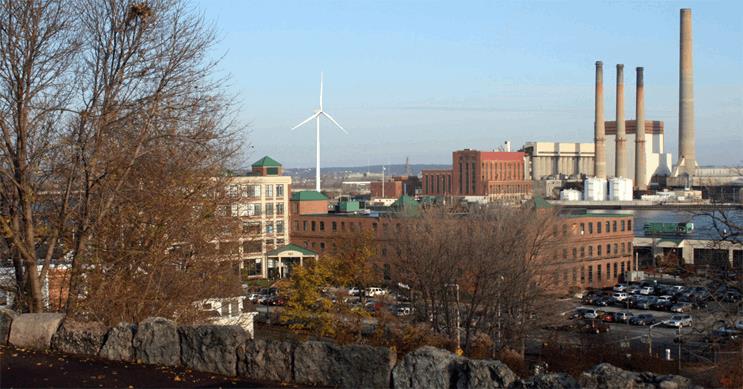

A year later EPA did it again in Massachusetts when it allowed Charleston’s drinking water authority to use half of its $5M in EPA funds to buy a 1.5MW turbine from the Chinese state-owned Sinovel. Local community activists complained that “building the wind turbine in China is not creating “jobs” here in the U.S. … (and) … the exemption allows the apparent circumvention of U.S. wind industry turbine setback guidelines and the Massachusetts 2009 model zoning ordinance/bylaws.”4 EPA trumps national guidelines and local ordinances, so to speak.

Artist rendering of Chinese-manufactured wind turbine in Charleston, MA (Source: Massachusetts Water Resources Authority)

Apparently, the EPA sees the threats of Chinese labor — and flailing wind turbine blades — as equally benign.

In addition to waivers, foreign goods leak through EPA procurements employing “substantial transformation” and “de minimis” loopholes.

Vendors can claim that their imported products have been ‘substantially transformed’ if “there is a change in the physical or chemical properties” or characteristics or use via U.S.-based processing. If imported goods are “transformed” in America they qualify as being “made” in America. The definitions don’t get much more precise, and each vendor unilaterally judges if their products are transformed and worthy of our tax dollars.25

Another trick is to categorize a foreign product as an “incidental item” that equals no more than five percent of the “total cost of the iron, steel, and manufactured good used and incorporated into a project.” With 3rd Grade math skills, anyone can machinate an item ‘incidental’ simply by engineering the size of the “project”.5

As EPA administers our tax dollars to rebuild our water infrastructure, it ought to support U.S. jobs and manufacturing to the greatest extent possible. At the least, the list of EPA waivers is a grand starting point for where we can hunt down new jobs. Fixing the leaks in the Buy American requirements will help.

References

- Federal Register. https://www.epa.gov/cwsrf/american-iron-and-steel-requirement-approved-national-waivers-0

- Federal Register, 10/20/2009, Notice of a Project Waiver of Section 1605 (Buy American Requirement) of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) to the Village of Ruidoso/City of Ruidoso Downs, NM

- Federal Register, 4/27/2010, EPA Notice of a Regional Project Waiver of Section 1605 (Buy American) of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) to the Town of Falmouth, MA

- https://windwisema.org/about/mwra_charlestown/

- OMB Requirement for Implementing Sec. 1512, 1605 and 1606 of ARRA, Federal Register, Vol44, No.77, April 3, 2009, pp18449.

About The Author

Mark Gibson is the principal at Kyklos Engineering, LLC, a public affairs and business development consulting firm. He has three decades of experience in energy and environmental policy and degrees in engineering and economics.

Mark Gibson is the principal at Kyklos Engineering, LLC, a public affairs and business development consulting firm. He has three decades of experience in energy and environmental policy and degrees in engineering and economics.

About “From Fish To Flint: Four Fixes For EPA’s Water Programs”:

While the new Administration sets about reform, we ought to consider how its new way of doing business can mend the serious flaws in the way the U.S. EPA adjudicates water. Cutting budgets and staff may feel good, but there’s much more to do. Whether you’re red- or blue-leaning, consider these basic, albeit contentious propositions to fix our most perplexing water challenges.

Read Part 1: Flint Failings And Our Crumbling Water Infrastructure, Part 2: Practical Cures For Abandoned Mines Pollution, and Part 3: Fixing The EPA's Clean Water Problem