Fixing The EPA's Clean Water Problem

Part 3 of a four-part series, “From Fish To Flint: Four Fixes For EPA’s Water Programs” (Learn more about the series.)

By Mark Gibson

A chasm in the Clean Water Act, coupled with EPA’s misguided direction, create an environmental suing spree that threatens to cost everyone that pays a sewer bill $100 billion and more — for pollution you didn’t cause, using remedies that don’t work. There’s a way to turn this around and help the taxpayer and the environment, based on lessons learned in Iowa and Idaho.

The year of the Apollo moon landing, Time magazine featured an arresting photo of the Cuyahoga River on fire, with flames leaping up from the water, engulfing a ship — a product of decades of pollution. The photo was actually taken in 1952, long before this transformational event that catapulted the environmental movement.

After 1969, the Clean Water Act became law, and we no longer see such carnage. Regulations on so-called “point sources” ratchet pollution so much that the industry now espouses “zeroemission” factories. But creating National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits has done practically nothing to abate eutrophication and severe water impairment. The ‘dead zone’ in the Gulf of Mexico and rampant algae blooms in Lake Erie are caused by excessive nitrogen and phosphorus — biologic building blocks (nutrients) — arguably the most prolific threat to water.1

Nutrient pollution is staggering. Algae blooms in Lake Erie deprived 400,000 people in Toledo of water and forced $13 million in water treatment. Galveston Bay suffered $15 million in shellfish bed closures. For every 10 miles that red tides affect Florida coasts, their communities lose $5 million a week in tourism. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates that dead zones cost over $82 million per year in lost fisheries and tourism.2,3 This is a worldwide problem, from the Baltic Sea to the Adriatic to the North Sea.

Mandates Miss The Point

The overwhelming source of this pollution is from so-called “nonpoint sources.” In EPA parlance, a nonpoint source is anything that isn’t a point source, i.e., anything without a discharge permit. The main cause of such nonpoint source pollution — the big elephant in the room that few wish to discuss — is agriculture. Agriculture is immune from the Clean Water Act, and few regulatory teeth exist to bite on other nonpoint sources, like golf courses, septic tanks, or dog poop.

None of this is lost on environmentalists. Since the turn of this century, the water litigation tool of choice has been the 303(d) impairment suit. Enviros’ 303(d) claims have amassed $80 billion in consent decrees against municipalities (that is, you and I), forcing construction of advanced sewage treatment and stormwater controls. The movement has leveraged total maximum daily load (TMDL) regulations, properly coined “Too Many Damned Lawyers.” It tries to force remedies for the Gulf of Mexico or any place where fish or fauna are harmed. As we saw during the Reagan Administration, during the Trump Administration we can expect environmental organizations to enjoy record fundraising, fueling a tidal wave of lawsuits. While litigation and public costs mount, it’s not doing much good.

Take the Chesapeake. Since 2003, about 500 sewage plants along the bay were forced to purchase $7 billion in upgrades, decreasing their phosphorus and nitrogen loads by 29 and 39 percent, respectively.4 Yet today, only 37 percent of the bay meets water quality standards, and 74 percent of the tidal segments have partial or full impairments, while 40 percent of the nutrient loadings are from agriculture and 19 percent from sewage plants (which load less nutrients than out-of-basin air pollution).5,6

A vexing aspect of EPA regulation is how liability for nonpoint pollution shifts to point sources. Under EPA guidance, “There must be reasonable assurances that nonpoint source reduction will in fact be achieved. Where there are not reasonable assurances … the entire load reduction must be assigned to point sources.”7 As a Park Foundation grant beneficiary from the University of Alabama School of Law relates, “Eventually, you end up with a horrible situation where you’re not complying with water quality standards, and the only choice is to make the point sources comply even more, or clean up their act even more at incredible cost, or to do more enforcement against the point sources.”8

Yes, that’s right: Via wastewater bills, you and I get to pay for agriculture’s pollution.

A few years ago, Denver’s wastewater authority was accused of impairing the South Platte River. Spurred by environmental litigation, the city was forced to buy advanced nutrient removal technologies for an extra $211 million.9 Denver wastewater officials testified, “In nutrient-impacted watersheds where point sources are a de minimis contributor ... it will be exceedingly difficult for ... utilities to garner community support and funding for expensive treatment technologies that result in little to no improvement in overall water quality. ... This is especially evident in the Gulf of Mexico and Chesapeake Bay.”10

The Iowa Example

In Iowa, a few dozen miles upstream of Des Moines, lay the most productive corn and soybean farming in the world. Called the Des Moines Lobe, it also produces the largest nutrient loads to the Gulf of Mexico.11 Not surprisingly, the Des Moines River’s average nitrate level veers to 13 mg/L, compared to EPA’s maximum limit 10 mg/L.12 The City of Des Moines uses this river for drinking water; its utility spends up to $7,000 daily for nitrogen treatment to produce legal drinking water. Another $180 million may be needed to treat the farm-impacted water.12 Ironically, a few miles downstream of Des Moines’ river intakes, their wastewater authority spent $1 billion for upgrades to reduce emissions.

So costly is Des Moines’ plight that its Water Works’ CEO (an attorney), Bill Stowe, is spearheading a groundbreaking lawsuit against upstream counties governing agricultural drainage districts in order to stop the districts’ nutrient releases. A true leader among water authority administrators, Stowe has stoked a virtual war in corn country: Big City vs. Rural Agriculture.

Yet, six months before Des Moines filed suit, a few miles from Stowe’s office, another brilliant leader, Dean Lemke, worked to address the problem at the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship. Lemke directed a precedential assessment of edge-of-field and on-farm nutrient reduction techniques when he published the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy. Apparently ignored by regulators was the report’s finding that constructed wetlands can reduce nitrogen loads for $2,800 per ton, bioreactors can do so for $1,800 per ton, and controlled drainage management and buffers work at $2,500 to $3,800 per ton.13 The report acknowledged that 130 of Iowa’s wastewater plants will be permitted to reduce nitrogen for about $6,800 per ton — in order to decrease statewide loads 4 percent.

Why are Iowa’s ratepayers subsidizing expensive sewage technologies for a mere 4 percent reduction? Such a scheme is like an elephant giving birth to a gnat: implausible and painful to watch.

Based on the state’s figures, if Iowans were to subsidize farm-centric mitigation rather than end-of-pipe wastewater technology, nitrogen loading could decrease threefold. As the EPA’s Iowa “regulate the wastewater plants” strategy inevitably fails, Iowans should expect their costs to go even higher as regulations spiral; engineering and construction firms win, farmers take flak, Iowa and the environment loses — just like the Chesapeake.

Cost-Effective Accountability

The economic elegance of mitigating nutrient sources near to the farm is bootstrapped by additional science.

Engineers from powerhouse Black & Veatch calculated what it would take to cut nutrients in the Illinois River Basin with simple near-stream treatment plants. Reducing nitrate loads to the Gulf of Mexico by up to 20 percent was estimated to require merely $760 million, at less than $2,000/ton of nitrogen removed.14 By comparison, Rockford, IL, spent an extra $30 million to remove about 3 mg/L of nitrogen, a marginal cost of around $5,000/ton.15 In the Chesapeake, enhanced nitrogen removal at sewage plants has cost $6,000/ton.16

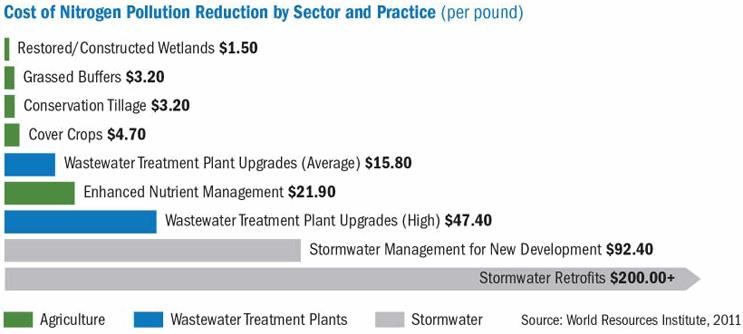

The Wetlands Initiative in Illinois analyzed seven Chicago wastewater plant upgrades. They determined 200,000 acres of passive wetlands would save $1.6 billion, compared to Chicago’s retrofits.17 From the National Association of Clean Water Agencies, “The cost to remove a pound of nitrogen or phosphorus from farm runoff and drainage is typically 4-5, sometimes 10-20, times less than the cost to remove the same amount from municipal wastewater or stormwater.”18

Confounding environmentalists is the reality that as EPA regulators force ratepayers’ wastewater upgrades, greenhouse gas emissions increase. Regulating nitrogen releases below 3 mg/L decreases nutrient loads by 1 percent, while increasing greenhouse gas emissions 70 percent.19 In the interest of the environment, when it comes to sewage regulation, we have come to the point of diminishing returns.

The Idaho Example

The saneness of nonpoint source cures is proven — under EPA permit — in Idaho. A growing city surrounded by phosphorus-rich farmland, Boise faced regulatory pressures on its sewage plant expansion. Avoiding costly conventional upgrades, the city devised a plan to treat agricultural runoff with simple alum-based dosing. Their Dixie Drain facility opened this year at a cost of $17 million, in lieu of spending $55 million for high-tech wastewater treatment. It only took Boise a decade with continuous congressional prodding to force EPA to agree to the innovation.20

This suggests a better way of doing business: Call it nutrient farming or nonpoint source mitigation; it’s really nutrient pollution offsets. As Boise shows, point sources should be encouraged to meet permit obligations with nonpoint source offsets — similar to Clean Air Act offsets.

Let’s get real. Regulating agriculture is off the table; it’s not going to happen in our lifetime — outside of a few communal conclaves in California. Barring a game-changing legal precedent out of Des Moines, the reality is that farmers will do what we pay them to do. It is economically and environmentally inefficient to expect otherwise.

A Path Forward

Conventional-thinking engineers argue that wetlands and bioreactors won’t offset pathogenic and other releases. Granted, but hybrid solutions controlling nutrients and pathogens collectively (basinwide) will maximize environmental quality at least cost — better than being held hostage to capital-intensive, high-tech contraptions tied to massive billable hours for consulting firms. New thinking and modern monitoring will remedy the challenges of aggregating and policing nonpoint source methods, as demonstrated by Dean Lemke’s amazing achievements at the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship — where the country’s most comprehensive plot-specific inventory of near- or in-field agriculture mitigation opportunities has been amassed.

It’s long past time for a new model. EPA must aggressively encourage NPDES permit holders with nutrient liabilities to employ offsets with simple, verifiable technologies. This must not be confused with “nutrient banking” or “water quality trading,” where environmentalists have hijacked these convoluted schemes and diluted them with “trading ratios” to foster perpetual condemnation of agricultural land.

We all eat food, and we’re all part of the nutrient cycle. If sewage fees are a proxy for our collective nutrient pollution, then (ratepayers’) wastewater authorities must be encouraged to seek least-cost paths to reduce basinwide pollution. EPA and its guidance should help leaders like Lemke and Stowe work together. As such an approach improves our water, support for environmental fundraising and 303(d) litigation evaporates.

References

- http://www.esa.org/esa/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/issue3.pdf

- https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-04/documents/nutrient-economics-report-2015.pdf

- http://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/regions/northamerica/areas/gulfofmexico/explore/gulf-of-mexico-dead-zone.xml

- https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-06/documents/wastewater_progress_report_06142016.pdf

- http://www.chesapeakebay.net/track/health/bayhealth

- http://www.cbf.org/about-the-bay/issues/dead-zones/nitrogenphosphorus

- EPA 1991 Guidance for Water Quality Based Decisions (EPA 440/4-91-001)

- http://www.circleofblue.org/2015/world/u-s-clean-water-law-needs-new-act-for-the-21st-century/ Andreen, Jones, “The Clean Water Act: A Blueprint for Reform,” Center for Progressive Reform, 2008.

- ftp://ft.dphe.state.co.us/wqc/wqcc/31_85NutrientsRMH_2012/RebuttalStatements/Metro.pdf

- Testimony of Barbara Biggs, before the Subcommittee on Water Resources and Environment, House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, U.S. House of Representatives, June 24, 2011.

- http://www.iowapolicyproject.org/2011Research/110622-wetlands.html

- Supreme Court of Iowa, Board of Water Works Trustees of the City of Des Moines, Iowa, vs Sac County, et al., No. 16-0076, January 27, 2017.

- “Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy”, Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship, Iowa Department of Natural Resources, May 2013. Released November 2012.

- Andrews, Barnard, et al, “An Innovative Approach to Nitrate Removal: Making a Dent in the Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia,” WEFTEC 2006.

- http://www.rrstar.com/article/20150418/NEWS/150419465

- Harper, Coleman, et al, “Analysis of Nutrient Removal Costs in the Chesapeake Bay Program and Implications for the Mississippi-Atchafalaya River Basin, 2008 WEFTEC Conference.

- http://www.prairiefirenewspaper.com/2008/08/nutrient-farming

- NACWA, “Controlling Nutrient Loadings to U.S. Waterways: An Urban Perspective,” 2011.

- Neethling, Reardon, HDR Engineering, “When do the costs of wastewater treatment outweigh the benefits of nutrient removal?” WERF, 2011.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Proposes to Reissue a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System Permit, West Boise Wastewater Treatment Facility, City of Boise, NPDES Permit No ID-0023981, October 2011.

About The Author

Mark Gibson is the principal at Kyklos Engineering, LLC, a public affairs and business development consulting firm. He has three decades of experience in energy and environmental policy and degrees in engineering and economics.

Mark Gibson is the principal at Kyklos Engineering, LLC, a public affairs and business development consulting firm. He has three decades of experience in energy and environmental policy and degrees in engineering and economics.

About “From Fish To Flint: Four Fixes For EPA’s Water Programs”:

While the new Administration sets about reform, we ought to consider how its new way of doing business can mend the serious flaws in the way the U.S. EPA adjudicates water. Cutting budgets and staff may feel good, but there’s much more to do. Whether you’re red- or blue-leaning, consider these basic, albeit contentious propositions to fix our most perplexing water challenges.

Read Part 1: Flint Failings And Our Crumbling Water Infrastructure and Part 2: Practical Cures For Abandoned Mines Pollution

Next up in the series: 'Buy American' Enforcement — Plugging Leaks