Using Water To Fight Lead In Drinking Water

By Cathy Proctor and Jay Adams, Denver Water

How Denver Water engineered a permanent solution to a legacy problem.

This is part two of a TAP series about the work that went into raising and maintaining the pH of the water Denver Water delivers as part of the utility’s groundbreaking Lead Reduction Program.

Protecting people from hazards that can lurk in their drinking water is the day-in, day-out job for water industry engineers, utilities and regulators.

And at Denver Water, efforts to protect people from the health risks posed by lead from old, lead service lines getting into drinking water, has been part of the job for decades.

There is no lead in the water Denver Water delivers to customers, but the utility regularly tests for lead in the drinking water of homes that are known to have lead water service lines, the primary source of lead in drinking water.

Rachel Himyak, water treatment lead, collects a sample of water that’s been run through old lead service lines as part of ongoing studies at Denver Water of pH adjustment. Photo credit: Denver Water.

In the first half of the 20th century, lead was a common, cheap and easy-to-work-with material to use when forming small pipelines that carry drinking water from utility pipelines in the street into customers’ homes. But these old lead service lines, which in Denver Water’s experience are more often found in homes built before 1951, pose a threat in the community, particularly to children, infants and pregnant women.

Denver Water has tested for lead in customers’ drinking water for decades under the Environmental Protection Agency’s Lead and Copper Rule. In 2012, the routine monitoring indicated the utility needed to investigate whether it could adjust the chemistry of the water it delivered to customers to better protect them from the risk of lead getting into drinking water.

In short, the results of tests on customers’ drinking water launched Denver Water into years of study centered on one question: What more could it do to better protect at-risk customers?

The first step was more testing.

“For a utility of our size and the number of lead service lines we have, you can’t just test something by putting it into the distribution system that’s delivering water to 1.5 million people every day. That’s not acceptable to us,” said Ryan Walsh, manager of the water treatment engineering section at Denver Water.

“We had to test things at a pilot scale, by doing the pipe loop study, before we could move forward.”

Walsh’s team was in charge of testing various treatment options via the pipe loop study and later planned, designed and executed the treatment plant systems involved in increasing the pH level.

Denver Water crews dug up old lead service lines from customers’ homes for years of study that led to the utility’s Lead Reduction Program. Photo credit: Denver Water.

To build the pipe loop study, Denver Water used old lead service lines its crews removed from customers’ homes (replacing them with lead-free lines) as the crews found the old lines during their regular work on water mains across the utility’s service area.

Denver Water plumbers connected the decades-old pipes together on racks and its treatment engineers ran water through them for hours, days and years. They tested different treatment methods to find out which worked best to reduce the risk of lead from the old pipes getting into the water passing through them.

Watch this video to see Denver Water’s pipe loop study, which is still underway today.

“That testing was so critical because we used the water that had been treated by our treatment plants, Moffat and Marston, the water that was going into our system to customers. The pipe loop study allowed us to test the adjustments we might do to the water to keep people safe,” said Patty Brubaker, a water treatment plant manager.

Aaron Benko, water treatment lead, pulls a sample of water from the rack of old customer-owned lead service lines that Denver Water crews dug up from customers’ homes and researchers continue to study. Photo credit: Denver Water.

“We tried different pH levels, we tried different phosphate levels, and we tried all of them on the actual lead pipes that had been taken from our system,” Brubaker said.

“There were so many people involved in putting this together. We had the crews who went out and pulled those lines, the plumbers that put them together on the racks, the people who made the adjustments and tested the water as it ran through the pipes.

All of us were studying the impacts to figure out which would be the best method to use to protect our customers from those old lead pipes.”

Decision Time

In March 2018, based on Denver Water’s studies, state health officials told Denver Water it had two years — until March 2020 — to get ready to start using a food additive called orthophosphate to tamp down the potential for lead to get into customers’ drinking water.

The decision worried many people inside and outside of Denver Water.

The concern wasn’t whether orthophosphate would reduce the potential for lead to get into drinking water. They knew it would.

Denver Water treatment engineers and operators (from left) Ryan Walsh, Aaron Benko, and Rachel Himyak at the pipe loop rack, which continues to have water running through the old lead service lines for ongoing studies. Photo credit: Denver Water.

Denver Water’s years of tests on the old pipes had shown orthophosphate would work, and other water utilities use orthophosphate to reduce the risk of lead getting into their drinking water.

But Denver Water, environmental groups and other water and wastewater utilities downstream of Colorado’s capital city worried about the widespread, long term — and expensive — consequences of adding orthophosphate to such a large system, including the increased potential for environmental impacts in and downstream of the Denver metro area.

Nicole Poncelet-Johnson, director of Denver Water’s water quality and treatment section, had been hired at the utility few months before the state’s 2018 decision on orthophosphate. From previous jobs involving water and wastewater treatment plants, she’d seen what orthophosphate could do at the plants and in the environment.

Hector Castaneda, a water treatment technician, and Nicole Poncelet-Johnson, director of Denver Water’s water quality and treatment section, at the Marston Treatment Plant filter beds, where water is filtered through tiny pieces of sand and anthracite coal as part of the treatment process. Photo credit: Denver Water.

“I’d seen the algae, which can grow faster when there are higher levels of phosphate in the water. I’d seen it coating the valves coming into the treatment plant so we couldn’t bring water in. I’ve seen how the taste and odor problems with the water were so bad that people bought and used bottled water instead of tap water,” Poncelet-Johnson said.

“And in Colorado’s dry, arid environment, with our long, sunny days and the UV light, adding orthophosphate to our system would have created a primordial soup. Plus, after the expense of adding it to the water at the drinking water treatment plant, it’s hard, expensively hard, to get phosphorous out of the water when it arrives at the downstream wastewater plants,” she said.

About half of Denver Water’s residential water use is outdoor water use used on lawns and gardens. Photo credit: Denver Water

On top of the expensive work that would be required at wastewater treatment plants, there simply was no way to recapture all the orthophosphate that would be added to Denver’s drinking water due to the way water is used in the metro area, she said.

About half of Denver Water’s residential water use is outdoor water use, tied to the irrigation of lawns and gardens. That means some of the orthophosphate-treated drinking water was bound to run off of lawns, down the gutter and end up in the metro area’s urban creeks, streams and rivers.

Water used for irrigation of lawns and gardens often ends up in urban creeks and streams that flow throughout the Denver metro area. Photo credit: Denver Water.

The groups worried that under the right conditions, that additional phosphate could accelerate the growth of algae not only downstream of the city, but also in the metro area’s urban creeks, streams and reservoirs.

There had to be another way, they said.

Alternative Path

“We went back to the data from the years of tests we’d run. We saw that if we raised the pH level of the water, instead of adding orthophosphate, we could protect people from the lead service lines,” Poncelet-Johnson said.

“And if we combined a higher pH with replacing those lead service lines with new, lead-free copper lines, then the lead levels would drop to the point where the tests couldn’t detect anything.”

In 2019, Denver Water formally proposed an alternative approach to state and federal regulators.

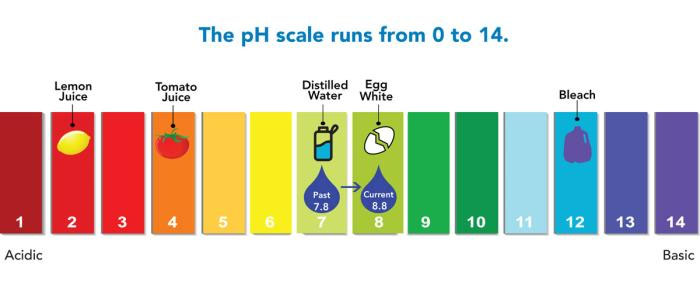

Denver Water’s proposal, at its core, called for raising the pH of the water delivered to customers from 7.8 to 8.8 on the pH scale, and keeping it there with relatively little variance as it flowed from the treatment plant to the customers’ homes and businesses.

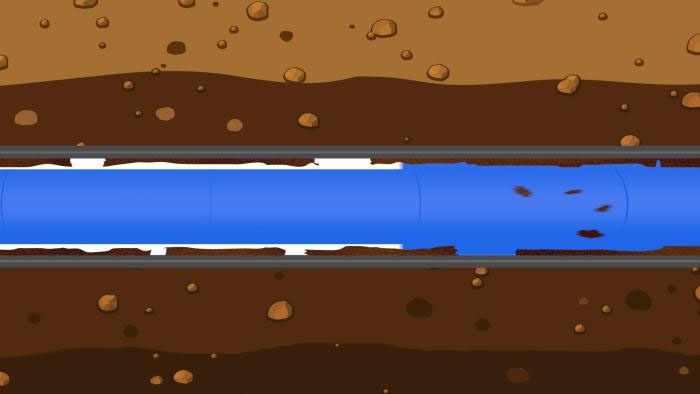

Raising the pH of the water delivered to customers strengthens an existing protective coating inside lead service lines, which reduces the risk of lead getting into drinking water. Image credit: Denver Water.

The higher pH level would strengthen an existing protective coating inside the lead service lines, reducing the risk of lead getting into the drinking water as it passed through the lead pipes.

And that — combined with significantly accelerating the replacement of the old lead services lines — would 1) lower the risk faster than relying on orthophosphate alone, and 2) do so without the cost and environmental concerns posed by adding the phosphate.

This graphic (not to scale) portrays how a higher pH level creates a stronger protective coating (shown in white and brown on the left) inside a lead service line (shown in grey), separating the water (blue) from the lead pipe and reducing the risk of lead getting into the drinking water. Image credit: Denver Water.

“It was a better solution, a permanent solution to the problem of old lead service lines, which are the primary source of lead in drinking water,” Poncelet-Johnson said.

“Because instead of a Band-Aid approach, instead of just adding chemicals to the system and then dealing with the widespread economic and environmental consequences of that decision for decades, we went the other way and proposed permanently removing the problem by raising the pH of the water and replacing the lead service lines,” she said.

Listen to Nicole Poncelet-Johnson, director of Denver Water’s water quality and treatment section, discuss Denver Water's Lead Reduction Program:

Denver Water’s alternative proposal focused on five areas:

- Raising the pH of the water it delivers to 1.5 million people to 8.8, and keep it fairly constant, with very little variance, as the water flowed from treatment plant, through the distribution system, to customers’ homes and businesses.

- Mapping the location of the customer-owned lead service lines in its service area and sharing that map with customers.

- Replacing the estimated 64,000 to 84,000 customer-owned lead service lines in its service area with new lead-free copper lines at no direct cost to the customer.

- Providing customers enrolled in the program with water pitchers and filters certified to remove lead to use until six months after their lead line was replaced.

- Launching the largest public health communication effort Denver Water had ever done to educate its customers about the risks of lead, the importance of using filtered water until the old lead service lines could be replaced, and the process for replacing those lead pipes.

Watch this video to learn more about lead service lines.

Breaking New Ground

The proposal broke new ground in the water industry in two main ways.

It attacked the legacy issue posed old lead service lines from all sides — by raising the pH level, replacing customers’ old lead service lines, providing water filters to customers enrolled in the program to use until six months after their line was replaced, and educating those customers about the program.

And Denver Water said it would tackle all those steps on a scale and at a speed never before seen in the water industry.

Communicating with customers enrolled in the Lead Reduction Program is one of five elements of the biggest public health initiative in Denver Water’s history. Image credit: Denver Water.

Other cities had aimed to replace a few thousand lead service lines.

But Denver Water proposed replacing up to 84,000 customer-owned lead service lines estimated to be in Denver Water’s service area, doing it at no direct cost to the customer, and doing it in 15 years.

And, the utility proposed sending water pitchers and filters to more than 100,000 households enrolled in the program to use for cooking, drinking and preparing infant formula until six months after their lead line was replaced.

More than 100,000 households enrolled in the Lead Reduction Program were supplied with water pitchers and filters certified to remove lead to use for cooking, drinking and preparing infant formula until six months after their lead line is replaced. Photo credit: Denver Water.

In December 2019, health officials at the EPA and the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment agreed to Denver Water’s alternative proposal.

Weeks later, in January 2020, Denver Water launched its Lead Reduction Program — and immediately faced a crucial deadline.

The utility’s engineers, treatment plant operators and monitoring teams now had to implement the systems and processes that would raise the pH level of the water and maintain that level as the water flowed across more than 3,000 miles of pipe to 1.5 million people. And they had less than 90 days to do it.

Stay tuned to TAP to learn how they did it in the third installment of our pH series, set to drop in the coming weeks.

If you missed part one of the series, click here to read it.