The 'Cap And Trade' Approach To Nutrient Removal

By Kevin Westerling,

@KevinOnWater

Forget “low-tech” — nutrient trading provides a no-tech solution for municipalities to gain compliance with effluent discharge requirements for nitrogen and phosphorus. The Mount Joy Borough Authority, profiled in this case study, was an early adopter and a model for a nutrient removal program that is gaining in popularity.

When it comes to nutrient loading into waterways, wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) aren’t the main problem, and yet they are the most accountable to regulatory authorities. In 2005, the Mount Joy Borough Authority (MJBA) wastewater treatment plant (WWTP), confronted by pending regulations for nitrogen discharges, turned to the agricultural community — a far greater source of nutrient loading — to help save the environment, as well as MJBA’s budget, by sharing the regulatory burden.

The solution derived at was nutrient trading, whereby local farms in the agriculturally rich region of Lancaster County, PA, improve their farming practices, lessen their nutrient load, and sell their gains as credits to the WWTP. At the time it was a novel idea (MJBA’s trade was the first in Pennsylvania); in the end, it was an award-winning strategy touted by the PA Department of Environmental protection (DEP).

Today, such programs are expanding throughout the Chesapeake Bay area — Delaware, Maryland, Virginia and West Virginia have also adopted programs (New York and Washington D.C. are the Bay watershed holdouts) — and are likely to proliferate elsewhere to coincide with fast-moving, national nutrient regulations. The MJBA story is a prime example of how nutrient trading can and should work for each stakeholder: farmers (or other certified dischargers), regulatory agencies, and, of course, municipalities.

A Cost-Effective Alternative

The Chesapeake Bay Tributary Strategy was conceived in 2000 with the long-term goal of having the Bay removed from the Federal Clean Water Act’s list of impaired waters, where it continues to reside. Enforced by the PA DEP, the plan required WWTPs discharging to Bay tributaries to comply with new nutrient limits by the 2010 deadline. With limits that were based on average daily flow (ADF), the total annual loads for MJBA, a 1.53-MGD facility, were set at 0.8 mg/L for phosphorus and 6 mg/L for nitrogen.

MJBA was readily meeting its existing 2.0 mg/L discharge limit for phosphorus, and was confident that the new limit could be met with more aggressive chemical treatment and tertiary filtering polishing, requiring no major equipment upgrades. However, the plant at that time (2005) was not subject to nitrogen regulations, and would not be able to meet the required levels without significant investment.

MJBA worked with ARRO Consulting, Inc. to evaluate its options for gaining nitrogen compliance, including chemical or synthetic denitrification using methanol or MicroC™, respectively, as prospective carbon sources. The former was not preferred because of its hazardous nature, and the latter for its expensive nature, according to Terry Kauffman. Kauffman now works as a commercial development strategist for ARRO, but was then the authority manager for MJBA.

Despite the reservations, MJBA went forth with the $4M plant expansion for biological nutrient removal (BNR) via methanol/MicroC, “just in case.” The capital equipment upgrades included a methanol tank, aeration tanks, and a biosand filter system. “We still have the methanol tank there,” said Kauffman. “However, the hope and prayer is that we don't have to use it.”

The Mount Joy Borough Authority (MJBA) wastewater treatment plant, built in 1956, has been through numerous upgrades.

Kauffman cites O&M, safety, and environmental reasons when explaining his preference for nutrient trading to meet total maximum daily load (TMDL) requirements. Whether using methanol or MicroC, O&M costs for physical nitrogen removal were estimated to be $135,000/year, while the cost of nutrient credits was estimated at $38,000 to $42,000/year. To illustrate the safety hazard, Kauffman noted that a brick wall had to be built around the methanol tank. “If someone was deer-hunting and accidentally shot the tank, it would explode. If it's that dangerous, do you really want to be putting that in the product you release into the stream?"

Strictly on the basis of capital expenditure, without even considering O&M, the estimated cost of removing nitrogen at the plant is at least $15.84 per pound. Meanwhile, the cost of one nitrogen nutrient credit (one credit = one pound of nitrogen removed) was negotiated in a three-year deal with nearby Brubaker Farms to be $3.81 — a savings of roughly $12/pound.

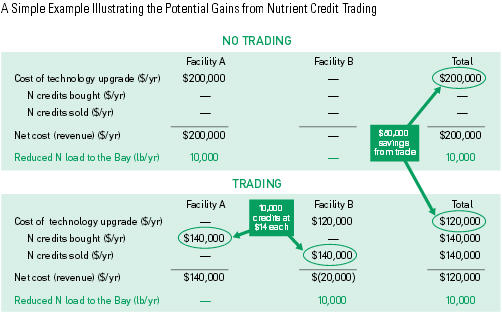

The farmer earns the credits, which are verified by DEP-designated or certified third-party entities, by instituting agricultural best management practices (BMPs) that reduce nitrogen and/or phosphorus loading. Number measurements of the impact of BMPs, however, are hard to quantify, so the PA DEP requires that municipalities must “overbuy” credits at a 2:1 trading ratio to ensure that nutrient loading is being adequately reduced. At worst (and by design), this creates a bank of available nutrient credits that are available “in case of emergency” — a miscalculation, for example, or a severe weather event. These extra credits can also be sold at auction to utilities facing noncompliance. Despite the “buy two, get one” rule, the savings that nutrient trading offers can be significant.

An extensive study by the Chesapeake Bay Commission, published in 2012, confirms its cost-effectiveness. The report concluded the following with regard to meeting phosphorus and nitrogen TMDLs for the Chesapeake Bay:

- “Significant” point source (SigPS) facilities — municipal WWTPs with capacity >0.4 MGD — are reduced by as much as 36 percent when SigPS facilities conduct nutrient trading with each other and with agricultural nonpoint sources in the same basin and state.

- If the geographic scope of trading extends beyond the basin and state to the entire watershed, potential savings increase an additional 35 percent.

- If urban areas are allowed to trade, compliance costs for SigPS facilities can be reduced by as much as 80 percent. This profound savings is attributable to the otherwise high cost of controlling nutrients from urban stormwater runoff.

Credit: Chesapeake Bay Commission

Ode To Mount Joy

When MJBA signed the contract with Brubaker farms, it was a first for the state of Pennsylvania, but now the program is off and running. In 2012, MJBA won the Governor’s Environmental Excellence Award for its pioneering efforts.

John Hines, who served at the time as the PA DEP’s executive director of the Water Planning Office, saw the potential of the program right away. “Groups like Mount Joy are learning firsthand how effective nutrient trading can be in meeting environmental goals at less expense than traditional command and control approaches,” he stated. “Mount Joy’s vision is a true showcase for many other local communities.”

Terry Kauffman, the former utility manager turned consultant, spreads the credit around. "We were very fortunate; our governing board was very much in tune with doing the project efficiently, but also doing it environmentally,” he remembers. “What MJBA did was based on the sense that it would work, but there were no guarantees. Not all governing boards will support those kinds of moves.”

Though he strongly advocates more nutrient trading, Kauffman understands the difficulty in adopting a solution outside the norm. “As a business owner or government official, you like to have hard facts on what your costs are. If you do a bricks-and-mortar solution, particularly when you borrow money, you can get a final determination on exact costs. So there is a tendency to go with the tried and true: if you buy a particular process, the manufacturer guarantees it. The owner of the facility doesn't have any responsibility. What MJBA did was based on the sense that it would work, but there were no guarantees. As it turns out, they ended up saving a significant amount of money over the years — and they're reducing chemicals.”

Pointing Municipalities In The Right Direction

Having been on both sides of the conversation, Kauffman recommends that plant managers challenge design engineers to provide alternatives beyond infrastructure investment alone, including combination solutions such as nutrient trading coupled with BNR.

"A lot of folks are up against a regulatory deadline, so they just rely on what their experts tell them: 'This will work; this will get you to compliance.’ I've seen prices as high as $30M for the upgrades," said Kauffman. "I also learned the hard way to ask about O&M cost. Methanol, for example, is a yearly, ongoing operational cost that you don't see in the bricks-and-mortar build."

Speaking of methanol, Kauffman makes a purely speculative, but potentially prescient, observation:

"Many plants are eliminating nitrogen and phosphorus, but adding chemicals — methanol and chlorine. What are the regulatory agencies going to say next, that we're going to eliminate chlorine? We already know that has hazard. I can just see methanol next. So why don't you try to find a solution that, as much as possible, removes those influences from the equation?"

A fine question, but the answers are not always readily available. Nutrient trading is offered in a handful of states, but the practice is still up-and-coming. Interested buyers and sellers can go here to learn about existing programs, while legislators can consult this primer for program adoption.

If it can do for others what it has done for MJBA, then let’s get trading!