My Most Personal Initiation To PFAS

When I attended the U.S. EPA-hosted PFAS Summit held at the Horsham, PA high school auditorium on July 25, 2018, the education I received from state and municipal leaders focusing on the local problem was more than just a professional briefing. It was ominously personal, due to the fact that the Water Online editorial office where I work and drink water every day is served by a utility sitting smack-dab in the middle of one of the most concentrated PFAS hotspots in the U.S.

Not every water utility faces PFAS concerns, but those who do can benefit from the experience of how Horsham and neighboring community utilities have met this challenge head-on. The combined presentations from the federal, state, and local officials at that summit also provide insights on related issues and actions taken to date.

The Nature Of The Problem

The EPA website addresses the PFAS problem with both background information and resources for dealing with it. In short, perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) — pronounced Pea’-fass — are a group of manufactured chemicals including perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), and their replacement PFAS formulas, such as GenX. PFOS and PFOA comprise chains of eight carbon atoms attached to fluorine and other atoms. Replacement chemicals, like GenX, tend to have fewer carbon atoms in the chain. In all, more than 3,500 PFAS-related compounds have been identified, but only a handful of them have been monitored.

The original PFAS applications included non-stick coatings, stain-repellant and water-repellant fabric treatments, and firefighting foams. That is why groundwater issues with PFAS have often been identified around manufacturing locations, airports, and the sites of large fuel or chemical fires in the past 50 years.

In Horsham, the problem reared its ugly head in 2014 when PFAS residuals from the use of airport firefighting foams at the Willow Grove Naval Air Station and Joint Reserve Base were detected in two drinking water wells. Another PFAS-contamination site had earlier been identified just three miles away, on the grounds of the former Naval Air Warfare Station in Warminster, PA. Since that time, multiple local municipal water utilities in the area have had to cope with a series of cascading revelations regarding the extent of the problem, and face the harsh realities regarding the cost of mitigating those problems.

An initial EPA provisional health advisory limit published in 2009 started at a level of 200 parts per trillion (ppt) for PFOS and 400 ppt for PFOA. In 2016, the EPA issued a lifetime drinking water health advisory level that lowered the threshold to 70 ppt for PFOA and PFOS combined.

Facing The Facts

At the Horsham summit, a panel of state experts from Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia health and environmental agencies recapped the evolving science on PFAS, along with related monitoring and communication issues, and the need for a coordinated effort among all parties. The consensus from multiple presenters on this panel revolved around four main points:

- Leadership. Most presenters stressed that the problem requires a holistic approach and that the federal EPA specifically needs to take the lead role in this problem.

- Regulatory Standards. A national-level focus is needed for regulatory definition of this dynamic topic, including establishment of health advisory levels (HALs) and maximum contaminant levels (MCLs).

- Testing. Multiple participants also stressed the need for more testing of wells and of individuals exposed to PFAS — especially among vulnerable populations such as the elderly, immunocompromised individuals, children, and pregnant women. A related need is to expedite certification of more testing laboratories to conduct tests on a growing volume of samples in a timely manner. A key element of biomonitoring has been the development of the PFAS Exposure Assessment Technical Tools (PEATT), which will now be used to track 500 randomly selected residents among the affected population of 84,000 people living in 32,000 households near the two former military bases. The study is expected to be completed by early 2019.

- Funding. Summit participants stressed that Congress needs to provide funding through the EPA or Department of Defense to address the known problem, in large part to provide the ability for local water systems to react more quickly.

Beyond remediation, one state water management administrator also noted that there needs to be more funding and emphasis on strategies for investigating historic land uses before approving applications for new wells. Points of consideration should include things like prior manufacturing activity or use of firefighting foam in surrounding areas that might affect the related aquifer.

Sharing Lessons From The Front Lines

While the EPA’s director of the Office of Ground Water and Drinking Water, Peter Grevatt, acknowledged during the event that it is “hard to appreciate the details” of the situation from Washington, D.C., the municipalities most intimately involved with the two former naval base sites demonstrated both great appreciation of the problem and great motivation in facing it head-on.

Horsham Township Manager Bill Walker described his township’s progression of action regarding the situation. It included:

- Complying with the initial Provisional Health Advisory Levels of 200 ppt for PFOS and 400 ppt for PFOA in 2014.

- Exceeding the EPA’s 2016 revised Health Advisory Level of 70 ppt, by establishing a goal of “non-detect” levels for the township’s Water Authority.

- Currently achieving a 4 ppt combined system-wide average for PFAS readings based on the adoption of granular activated carbon (GAC) treatment and purchasing water from other unaffected sources.

The township’s out-of-pocket expenses to date for dealing with the emergency are approaching $1 million, with subsequent costs for operating the GAC systems on all its wells estimated to be $1.2 million annually. Those financial impacts do not include any losses in local real estate valuations and employment levels. Walker’s summary recommendation was straightforward and succinct, “Education. Communication. Remediation. Compensation.”

Warminster Township Municipal Authority General Manager Tim Hagey echoed similar experiences and went several steps further. Warminster shut down water pumping upon notification of high PFAS levels, but was back in operation in six days, using temporary treatment. Today the township uses a combination of GAC treatment and outside water purchases from uncontaminated neighboring utilities. Still, Hagey cites the biocumulative nature of PFAS and the fact that some residents have been exposed for decades as reasons for not viewing the 70 ppt combined PFOS/PFOA as acceptable. He cited challenges with GAC treatment and says his utility is working toward approval for a resin treatment solution. Ironically, getting permits for an alternate treatment such as ion exchange resin is proving to be difficult, considering the fact that PFAS is not regulated.

Additional local municipal presentations were equally thorough and professionally presented, documenting varying levels of response from the Navy, Department of Defense, and EPA without hyperbole or finger-pointing. Most concluded that more testing is needed, that the responsible parties should solve the problem — including public water hookups for residents with polluted private wells — and that ratepayers should not shoulder the costs as the municipalities strive for non-detect levels of PFAS.

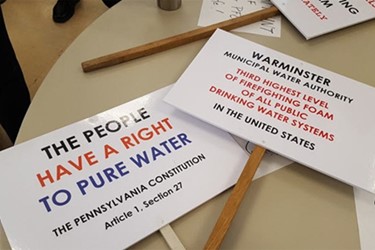

The audience absorbed the information quietly and politely, reacting with applause only once — when Warminster Township Manager Greg Schuster requested that the EPA and DoD departments be consistent in reacting to the situation with “a sense of urgency,” saying “Treat us like your family.”

The Human Side Of The Story

The Horsham panel presentations concluded with feedback from three local residents who belong to the National PFAS Contamination Coalition, which represents PFAS-affected members from 58 communities across 11 states and Guam. That group’s goal is to set protection levels for all chemicals in the class of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

One of those presenters was personally fighting cancer and one had a child affected by cancer. The third lived in an adjacent township that took no action even after two of its wells tested positive for PFAS, because the levels did not yet exceed 70 ppt. The collective concerns of those three coalition members added new perspective to the conversation:

- State and federal responses have been inconsistent, and there are no enforceable state or federal regulations to date. There is also a lack of information on how PFAS combines with other contaminants.

- There is no federal response for private wells below the 70 ppt standard, even though it has been shown that low levels of certain PFAS compounds in drinking water threaten the health of children and that PFAS can be passed along to children through breast milk.

- Limited lab resources for blood and water testing make testing time-consuming, expensive, and relatively inaccessible.

- Poor communication has been evident in the withholding of the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) report for six months, late postings of meeting notices, and adjacent landowners not being directly notified of nearby contamination.

- All PFAS compounds and replacements should be regulated as a class, since many are just as toxic as those currently being assessed.

Finally, the coalition representatives emphasized the need for impacted residents to have a seat at the table in ongoing PFAS discussions. They noted that representatives from state government and environmental groups and agencies were invited to participate in the first EPA National Leadership Summit on PFAS, but impacted private citizens were not. The coalition takes the position, “Nothing about us, without us.”

So Where Do We Go From Here?

While the local municipalities have taken the most aggressive steps to protect their residents — going above and beyond federal guidelines — they still need the backing of federal entities to formalize stronger standards and enforce remediation by the parties that caused the contamination. Improved response times and improved funding are two of their biggest requests.

As I exited the high school parking lot on my way back to the office, I was struck by the stark image of the old airbase radar tower silhouetted against the blue sky less than a quarter-mile away. That visual impact caused me to shudder for a second as I realized that the local officials and residents I had just heard from have lived, worked, and governed in the contaminated shadow of that tower for years. It still stands as a constant reminder of the genesis of their current PFAS battle, and it made both their responses and their recommendations all the more meaningful to me.