GAO Report Promotes New Way To Advance LSL Remediation

In a report released just four days before the U.S. EPA issued its final revisions to the Lead and Copper Rule (LCR) on December 22, 2020, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) provided insights that water utilities can use to achieve better protections for water customers in neighborhoods at higher risk of lead exposure. Here are links to the complete GAO risk-of-lead-exposure report and an overview of its four recommendations, which the GAO anticipated updating in response to the EPA’s LCR final revisions. Water utilities can use the experience outlined in the report to focus attention on high-risk areas in their systems and accelerate their own efforts to identify and replace problematic lead service lines (LSLs).

Making The Best Of A Bad Situation

The GAO report looks at ways water systems can use geospatial LSL data and U.S. Census data to help identify high-risk areas relative to LSLs. It noted that, as of September 2018, “the total number of lead service lines in drinking water systems is unknown, and less than 20 of the 100 largest water systems have such data publicly available.” The performance audit outlined in the report covered the timeframe between May 2019 and December 2020, and the resulting report cites four key recommendations:

- “EPA's Assistant Administrator for Water should develop guidance for water systems that outlines methods to use ACS (American Community Survey) data and, where available, geospatial lead or other data to identify high-risk locations in which to focus lead reduction efforts, including tap sampling and lead service line replacement efforts.

- “EPA's Assistant Administrator for Water should incorporate use of (1) ACS data on neighborhood characteristics potentially associated with the presence of lead service lines and (2) geospatial lead data, when available, into EPA's efforts to address the Federal Action Plan to Reduce Childhood Lead Exposures and Associated Health Impacts.

- “EPA's Assistant Administrator for Water should develop a strategic plan that meets the WIIN (Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation) Act requirement for providing targeted outreach, education, technical assistance, and risk communication to populations affected by the concentration of lead in public water systems, and that is fully consistent with leading practices for strategic plans.

- “The Administrator of EPA should establish a time frame for publishing new risk communication guidance or updating existing risk communication manuals.”

In an undated reply letter from the EPA to the GAO included in the body of the report, the response to the first three recommendations was “EPA disagrees with the recommendation and will be unable to provide additional feedback until the Lead and Copper Rule is completed.” In response to the fourth recommendation, the EPA noted its agreement and reported that it was in the process of updating its risk-communication website, with completion anticipated in March 2021. The EPA also noted that it had even started a series of training sessions on risk communication in advance of that website revision.

What’s In It For Utilities?

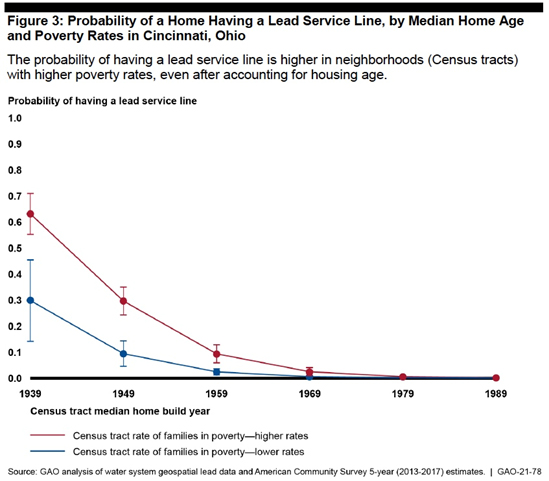

While much of the background information about water distribution networks — distribution-line layouts, LSL configurations, etc. — referenced in the report will be familiar to water distribution professionals, the report also identifies non-utility data sources that can help to identify high-risk areas for LSLs. Given that LSL issues often correspond to neighborhoods with higher poverty rates (Figure 1), part of the GAO effort reflected social vulnerabilities referenced in the provisions of Executive Order 12898 (Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations).

Figure 1. This chart incorporated in the GAO report demonstrates differences in the probability of LSL presence based on house age and available census data on poverty rates.

The good news is that even if the EPA does not develop guidance for using the Census Bureau’s ACS data, the GAO report provides a framework that utilities can employ to analyze areas of higher LSL probability based on their own local conditions. Although smaller utilities might not have the in-house expertise to conduct similar studies themselves, the report does provide guidelines that third-party analytical specialists can use to replicate the approach.

The underlying message is that utilities can use census demographic data or blood-lead-level data in lieu of unavailable geospatial lead data or in conjunction with utility records to do a better job of prioritizing areas for concentrated LSL identification and removal efforts to achieve greatest risk-reduction success. For example, in all four cities studied in depth — Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, Providence, and Rochester — several common housing or demographic factors universally appeared as census-tract indicators of increased likelihood of LSLs:

- Percentage of multi-unit dwelling households.

- Median home age.

- Percentage of families in poverty.

- Percentage of population that is unemployed.

- Percentage of households without a vehicle.

Good Communication Is Fundamental

According to its website, GAO is an “independent, non-partisan agency that works for Congress” and functions as a “congressional watchdog” to help government work more efficiently. While the GAO report acknowledges differences of opinion between that organization and the EPA regarding certain legal and technical interpretations, local water utilities can still benefit from absorbing and employing perspectives included in the report. One is the importance of good public-education materials on risk information, lead sources, and actions to reduce exposure to lead in drinking water — whether communicated in printed materials or on water utility websites (examples and guidelines are provided). This is critical because in the report’s review of 54 water systems, communicating health effects for at-risk populations was rated as the weakest area of communication.