A New Perspective On Funding Nonpoint-Source-Pollution Solutions

While municipal wastewater treatment facilities fight hard to keep waterways clean, other (“nonpoint”) sources contribute greatly to environmental pollution. But there is funding, and now guidance, available to help solve the problem.

For more than three decades, Clean Water State Revolving Funds (CWSRF) have been helping states, municipalities, and environmental groups reduce pollution pressures on the nation’s waterways. But people might be shocked to learn how disproportional funding has been for addressing point source pollution vs. nonpoint source (NPS) pollution.

The recently released U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) document, CWSRF Best Practices Guide for Financing Nonpoint Source Solutions (EPA 84121012), is designed to improve that imbalance (Figure 1). It offers a broad perspective on putting CWSRF funds to use properly, creative ideas for navigating the technical constraints of such funding programs, and real-world experience from states that have successfully tackled a variety of NPS challenges.

Figure 1. This 60-page document outlines the importance of Clean Water Act programs focused on nonpoint sources (NPS), best practices for successfully funding such programs, and examples of successful NPS-related projects — ranging from urban and agricultural runoff to stream and wetland restoration to septic system upgrades and more. (Source: U.S. EPA)

Time For A Change

Pollution in any form or from any source is a threat to clean water goals. Some forms might be more acute or immediately destructive than others, but all have the potential to compromise quality-of-life issues for humans and wildlife alike. Despite the overall successes of the CWSRF program, its expenditures have been primarily focused on point-source pollution problems. Consider these statistics outlined in the new best practices document:

- More than 90 percent of the $145 billion spent to date under CWSRF financing has been focused on point source pollution management efforts.

- Approximately three-quarters of instances classified under the EPA’s Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) program are attributed primarily to NPS, yet less than 4 percent of CWSRF funding has been devoted specifically to addressing NPS needs.

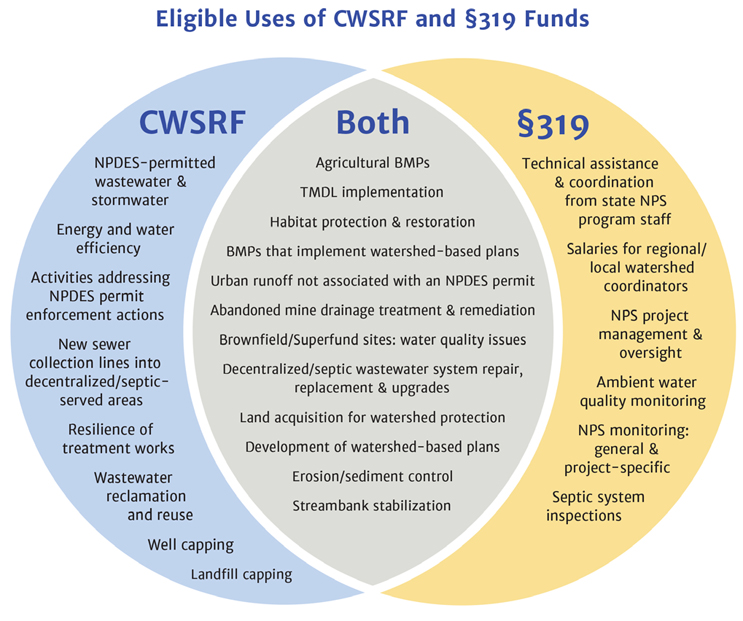

In an attempt to balance that focus, the new EPA document explores eligibility requirements, best practices related to leveraging CWSRF funding for NPS projects, ways to bolster CWSRF funding with other funding sources, and various mechanisms to make funding more accessible to partners in NPS pollution control and remediation efforts (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The new EPA guide is a combination of educational and action-oriented resources, ranging from eligibility requirements to financing opportunities (shown above) to customized strategies for NPS programs. It also provides readers with scores of URL links to more detailed national program resources and informational websites, state-specific programs, and footnoted resources used to develop the guide. Source: CWSRF Best Practices Guide, Figure 1-2)

NPS Strategies At Work: Encouraging More Of A Good Thing

The guide offers some thought-provoking suggestions that water-use leaders can use to improve the brainstorming, selection, and implementation of new NPS pollution reduction solutions. Here is a cross-section of those possibilities:

- Aligning Water Quality Goals/Priorities – Recommendations include assessing targeted issues to address, looking for changes state CWSRF programs can make to facilitate financing, and creating opportunities for innovation and collaboration. That includes building on the work of others to customize specific strategies to suit the challenges at hand.

- Identifying Barriers – Addressing historic barriers in the administration, funding, and loan repayment of NPS projects is an important step toward increasing the opportunities for attacking NPS challenges. By outlining new strategies and past examples of how to navigate those barriers, this document can help state administrators revisit their ongoing challenges with a new eye toward making the system work for them.

- Alternate Funding And Repayment Resources – These include options for NPS project co-funding, alternate financing mechanisms, and creative avenues for loan repayment — such as targeted fees, taxes, carbon credits, sales/ rentals, etc. — as well as informing stakeholders about financial incentives.

- Encouraging Partnerships – Municipal and nonprofit organizations wanting to improve upon current NPS pollution problems can benefit from working with allies, especially those who have experience with related efforts. Collaborative efforts among stakeholders from watershed groups, private homeowners, energy utilities, and other governmental organizations can pay off in making it more practical to achieve new CWSRF environmental improvement goals.

The Proof Is In The Performance

Finally, to encourage realistic new actions to bolster NPS clean-up efforts, the guide outlines a series of case study projects tailored to state-specific CWSRF regulations and creative funding options. These projects are currently paying dividends in clean water applications from coast to coast.

- Making CWSRF Funding Work for NPS Efforts – Learn how Ohio, Iowa, and Minnesota leverage between approximately $300 million and $500 million each in CWSRF financing through private borrower funding and pass-through loans for improving or replacing septic systems, restoring stream banks and habitats, controlling erosion, and helping to fund agricultural best practices.

- Wastewater Upgrades – In the state of Washington, collaboration among the state’s Department of Ecology, Department of Health, county or local health departments, and community development financial institutions is providing access to financing for repair and replacement of failing septic systems.

- Agricultural Nutrient Management – The Agricultural Water Quality Loan Program in Arkansas improves water quality by funding a variety of eligible practices ranging from riparian buffers to animal waste management/storage to drainage system outlets to livestock watering facilities, and more.

- Natural Restoration – Projects sponsored by traditional utilities in Iowa are being used for activities such as streambank stabilization, native vegetation restoration, and capturing stormwater via rain gardens and permeable paving. NPS projects coupled with a more traditional publicly owned water utility project in the same watershed earn a reduced interest rate.

- Forest Thinning And Wildfire Restoration – Read how the state of Arizona worked to reduce the threat and impact of wildfires that generate NPS pollution.

Learn More

Government and nongovernment organizations interested in generating more funding opportunities to protect their local waterways and environment from NPS pollution can download the guide from the EPA website.

About The Author

About The Author

Pete Antoniewicz is an industrial content writer at Water Online, where he draws on his journalism degree and experience writing for a variety of industrial and high-tech companies.