Utility Safety Culture: A Hidden Key To Employee Retention

Sound safety policy does more than keep your workforce free from harm. It keeps them around.

The liquid utility field (water and wastewater treatment plant and field workers) most often falls in the category of unsung heroes or workers who are taken for granted. This professional disconnect can be due to the negative connotation led by the name “wastewater” or the entry-level position’s being a high school diploma or equivalent. Many liquid utility workers may be fighting an uphill battle in gaining respect from engineering groups, city and county management, or even support personnel in the management team of the utilities’ administration offices. However, all operators must have on-the-job experience and some technical training to obtain a state license. Once operators become licensed, their value increases as current employees age and the job market expands due to regulatory concerns. Some operators leave one municipality for another due to an increase in salary, better schedules, and better working conditions. This article will highlight how having a good safety culture can help the municipality retain promising workers.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) projected the need for water and wastewater operators to increase by 6 percent from 2014 to 2024 (the average national rate for all occupations).1 But are the municipalities filling vacancies at the same rate of attrition due to retirements or workers leaving the industry for better working conditions? Do the operators feel that they are valued as workers and safe on the job? These are core questions that lead to the retention of utility workers.

The BLS notes that utility workers are at a higher risk of injury and illness than most.2

There have been a few fatalities making national news that could have easily been prevented by having a better safety culture at the utility.

- “Water Workers Recover Inspector’s Body From Municipal Tank” (Massachusetts, Dec. 2016)

- “NYC Contractor Dies After Falling Into Wastewater Tank” (New York, Oct. 2016)

- “Second Worker Dies From Accident At Wichita Falls Treatment Plant” (Texas, July 2016)

- “Wastewater Worker Dies After Falling Into Toxic Sludge Basin” (New Mexico, July 2016)

OSHA notes that worker safety is a key to worker retention, increased productivity, lower workers’ compensation costs, and increased revenue. Employers that have an active safety and health program that values safety over compliance with rules or regulations are rewarded with the benefits previously listed. A safety culture is the value system from top management to the new hire that promotes a proactive approach to finding and fixing workplace hazards as a way of doing business. Safety is not “first” as most signs and promotional materials mention, but safety is incorporated seamlessly into operations.

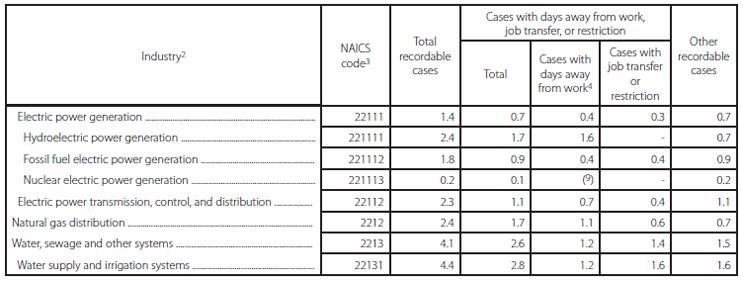

Table 1. Incidence rates* of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses by industry and case types (2015)

*The incidence rates represent the number of injuries and illnesses per 100 full-time workers and were calculated as: (N/EH) x 200,000, where: N = number of injuries and illnesses; EH = total hours worked by all employees during the calendar year; 200,000 = base for 100 equivalent full-time workers (working 40 hours per week, 50 weeks per year).3

There are seven interrelated elements in creating an integrated safety culture for any business or utility. Each core element must be developed to its fullest potential for the culture to develop and flourish. The seven elements are as follows (adopted from the OSHA safety and health model4):

- Management Leadership

- Worker Participation

- Hazard Identification and Assessment

- Hazard Prevention and Control

- Education and Training

- Program Evaluation and Improvement

- Communication and Coordination for Host Employers, Contractors, and Staffing Agencies.

Management Leadership

Utility directors, plant managers, and shift supervisors are all considered managers in some form or fashion. A committed management unit provides clearly defined objectives and goals for organizational safety behavior. They finance the activities of safety through purchases and resource allocations. Every level of management values safety practices and accomplishments as much as regulatory compliance to water quality.

Steps to implement leadership commitment to safety:

- Write or personally sign a clearly defined safety policy that acknowledges that safety and health are as important as productivity, water quality, regulatory compliance, and customer service

- Communicate the policy and values to all levels of the organization

- Visually set examples of safety behavior and demonstrate actions consistent with a safety culture

- Allocate resources for safety and health

- Hold all levels of the organization accountable for safety performance.

Worker Participation

Workers must feel valued in the entire process of developing a safety culture. Without the workers’ participation, the transition will be forced and doomed to fail because of the constant reinforcement of rules and internal regulations. Supervisors will then be forced to punish unsafe behavior disproportionately to rewarding safe behaviors. Workers should feel empowered to:

- Access information regarding safety and health policies

- Participate in all phases of the program’s design and implementation

- Report injury and illness without retaliation or adverse consequences

- Suggest how to remove barriers to health and safety

- Hold peers and management accountable for safety and health.

Hazard Identification And Assessment

A hazard is any condition or action that can cause an organizational loss. An organizational loss can come in the form of an injury, illness, damaged equipment, or even worker turnover. When a loss occurs, the organization must determine the root cause of the loss and not just the symptoms leading to the loss event. The assessment process must be structured and detailed and deliver actionable measures to address the root cause. Hazard identification and assessment can be accomplished by:

- Worksite analysis of past, present, and predictive data from reports, instrumentation and maintenance logs, and worker injury and illness records

- Worksite inspections for safety hazards

- Investigations of each accident until the root cause is completely disclosed

- Identification of hazards that may arise outside of normal operating conditions, including emergencies, startup, or shutdown operations

- Characterization of the true composition of a hazard — assign a priority value and identify appropriate hazard controls.

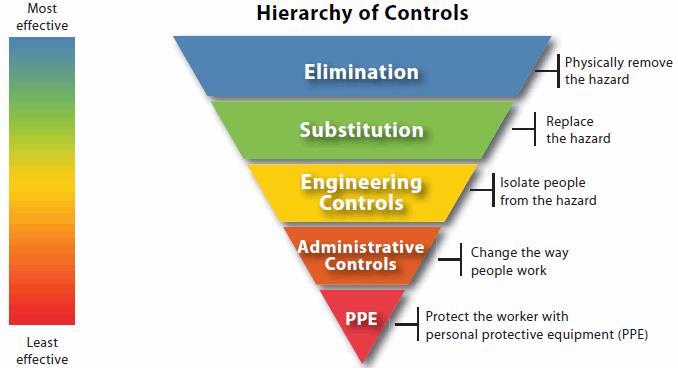

Source: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

Hazard Prevention And Control

The prevention and control of hazards protects the worker from injury and illness and also gives employees a clear sign that the utility cares about their well-being. Elimination of hazards is the best way to avoid an organizational loss. However, that may not be possible in all situations. Therefore, hazard control is appropriate for some hazards that are still present when workers are performing their daily tasks. Although some utilities are substituting highly hazardous chemicals, such as liquid chlorine for chlorine gas, it is mostly because they are trying to avoid the risk management program regulated by the U.S. EPA and not primarily for worker safety. The hierarchy of hazard controls after elimination and substitution includes:

- Engineering (physical barrier device, such as a machine guard)

- Administrative (work rule, such as work rotation)

- Personal Protective Equipment (protection worn by workers as a barrier to hazards, such as a hard hat).

Tips for implementing hazard prevention and controls are as follows:

- Identify what controls are available for each type of hazard

- Select the proper controls by doing a detailed hazard assessment

- Develop, maintain, and update a hazard control plan

- Select controls that are applicable for all aspects of the organization and conditions

- Implement the selected hazard controls with a priority on elimination and substitution of hazards

- Follow up on all hazard controls for each task to make sure they are protective enough.

Education And Training

Education and training can be thought of as a tool that binds each step together to keep the efforts cohesive. Some utilities have relied on safety training from organizations or even videotapes with outdated material. The role of education and training must be a factor in developing both management and workers to create the overall safety culture. General workers should have safety awareness training with regular operations or maintenance training. However, if they work in a specialized area that exposes them to unique hazards, then training must be applicable to that hazard. Effective training can be done peer-to-peer, in formal classrooms, online, or at the worksite. Some action items suggested by OSHA are:

- Provide program awareness training

- Train employers, managers, supervisors on their individual safety roles

- Train workers on their specific role in the safety program

- Train workers on hazard identification and controls.5

Program Evaluation And Improvement

Every program in an organization must be vetted and improved in order to stay viable and productive; safety programs are no different. This effort of program evaluation must be made in a given interval and by a competent group. If there are deficiencies found in a program, then the corrections must be made in a systematic way by high-risk issues being fixed first and lower-risk areas last. Risk can be calculated as Probability x Severity = Risk. The probability of a loss event occurring can be broken down into five categories:

- Improbable

- Unlikely

- Probable

- Likely

- Frequent.

Severity speaks of the consequence of a loss event when it does occur:

- Minor

- Marginal

- Serious

- Catastrophic.

If your risk assessment tells you that a task is a P4 x S3 = R12, then it should get your attention over an R3 item.

Program evaluation and improvement must include the following areas:

- Monitoring performance and progress

- Verifying the program is implemented and is operating

- Correct program shortcomings and identify opportunities to improve.6

Communication And Coordination For Host Employers, Contractors, And Staffing Agencies

The utility must take responsibility for all workers, including contract and staffing agency workers. Many utilities are not under the jurisdiction of federal OSHA or even a state OSHA, but the contract companies are under an occupational safety agency that will regulate and cite them for violations. However, local government officials have a moral obligation to make sure that workers of all types that do business with them are protected from hazards. To keep the workers safe, the utility should:

- Communicate with all outside contractors the importance of worker safety

- Coordinate with supervisors, owners, and workers throughout the project to make sure the worksite is safe

- Hold all workers and agencies accountable for operating a safe worksite

- Verify that the bids and contracts specify that safe work practices are a must for working with the municipality.

A safety culture will protect the worker from injury and illness because the utility places a value on the lives of the workers. This is a deposit into the “goodwill” bank of the worker and will be rewarded with loyalty. A deep commitment to a safety culture will lead to worker retention and organizational benefits far beyond regulatory compliance.

References:

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), U.S. Department of Labor (https://www.bls.gov/ooh/production/water-and-wastewater-treatment-plant-and-systemoperators.htm#tab-6)

- BLS, North American Industry Classification System, NAICS code 221300 (https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/naics4_221300.htm)

- BLS (https://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/osh/os/ostb4732.pdf)

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (https://www.osha.gov/shpguidelines/docs/OSHA_SHP_Recommended_Practices.pdf)

- OSHA (https://www.osha.gov/shpguidelines/education-training.html)

- OSHA (https://www.osha.gov/shpguidelines/program-evaluation.html)

About The Author

Sheldon Primus is a certified occupational safety specialist with a masters of public administration with a concentration in environmental policy. He is part of the first class of six operators to receive the Professional Operator (PO) designation from the Certification Commission for Environmental Professionals (C2EP) of the Association of Boards of Certification (ABC). Additionally, he is a trainer for the Certified Occupational Safety Specialist (COSS) program of the Alliance Safety Council-Baton Rouge, LA. Sheldon is owner/CEO of Utility Compliance Inc., its subsidiary OSHA Compliance Help, and the online water/wastewater/safety training school Primus Institute. E-mail: sheldon@utilitycompliance.com or sheldon@oshacompliancehelp.com.

Sheldon Primus is a certified occupational safety specialist with a masters of public administration with a concentration in environmental policy. He is part of the first class of six operators to receive the Professional Operator (PO) designation from the Certification Commission for Environmental Professionals (C2EP) of the Association of Boards of Certification (ABC). Additionally, he is a trainer for the Certified Occupational Safety Specialist (COSS) program of the Alliance Safety Council-Baton Rouge, LA. Sheldon is owner/CEO of Utility Compliance Inc., its subsidiary OSHA Compliance Help, and the online water/wastewater/safety training school Primus Institute. E-mail: sheldon@utilitycompliance.com or sheldon@oshacompliancehelp.com.