U.S. Military Bases With Cancer-Linked Contaminated Water Are Undercounted

By Environmental Litigation Group P.C.

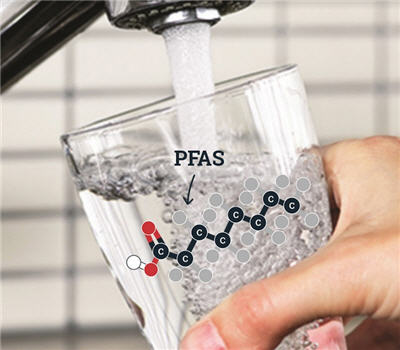

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a group of an estimated 5,000 man-made fluorinated chemicals that have been used, since the 1940s, in the manufacturing processes of various consumer products and industries. PFAS are widely used, especially because of their oil and water repellency and temperature and chemical resistance.

According to the U.S. EPA, PFAS are found in the aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF) that the military has used for extinguishing aviation fires since the 1970s. As such, they are an important source of contamination in areas where firefighting training occurs.[1]

In 2017, the Pentagon released its first assessment of the levels of PFAS in its water systems. It reported that there are 401 known military facilities where PFAS were used.[2] At least 297 of these locations tested positive for contamination in wells, on-base drinking sources, and groundwater.[3]

An update on the situation came in September 2019 when Robert McMahon, a senior Pentagon official — currently resigned[4] — said that the initial installations number of 401 is likely to go higher and that the scope of the problem can only be known after much more analysis and investigation into the sites.[5] Accordingly, new information estimates contamination on or around at least 425 military sites, including National Guard facilities.[6]

Data obtained from the Department of Defense (DOD) by the Environmental Working Group (EWG), under the Freedom of Information Act, show that locations with notably high levels of total PFAS include Fort Leavenworth, in Kansas; the Joint Forces Training Base, in California; Belmont Armory, in Michigan; McChord Air Force Base, in Washington; Fort Hunter Liggett, in California; and the Sierra Army Depot, in California.[7]

"Since the PFAS in the firefighting foam have been linked to cancers and birth defects, many veterans want to know whether the use of the foam is the cause of the cancers they or family members have faced," says Don Blankenship, attorney at Environmental Litigation Group P.C.

In the aftermath of the contamination, communities near military bases have demanded that DOD clean up their water. The state of New Mexico went further and filed a lawsuit over water contamination to force faster cleanup or compensation.

PFAS Health Effects

PFAS remain in the environment and cannot be broken down into other substances through ordinary chemical processes. They can persist in nature for hundreds, or possibly even thousands, of years.

PFAS remain in the environment and cannot be broken down into other substances through ordinary chemical processes. They can persist in nature for hundreds, or possibly even thousands, of years.

These man-made chemicals accumulate throughout life in humans and animals, especially in the liver, kidneys, and blood.[8] This increases the risk of getting diseases. From research and regulatory perspectives, considerable attention has been given to a few PFAS, especially to the two most common types, perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA).

Most of the well-studied PFAS are considered to have moderate to high levels of toxicity, affecting particularly the development of children. Children and the elderly may be the most vulnerable population groups to PFAS contamination, but everyone exposed to high levels of PFAS is at risk of adverse health effects.

Some studies have shown that the effects of PFAS on human health include:[9]

- Thyroid disease

- Increased cholesterol levels

- Liver damage

- Kidney cancer

- Testicular cancer

- Delayed mammary gland development in unborn children

- Reduced response to vaccines in unborn children

- Lower birth weight in unborn children

Other diseases linked with lower certainty to PFAS contamination include:

- Breast cancer

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Increased time to pregnancy

- Pregnancy-induced hypertension

- Obesity in unborn children

- Early puberty onset in unborn children

- Increased pregnancy loss

- Low sperm count and mobility in unborn children

PFAS Contamination Of Drinking Water Is Underestimated

People are exposed to PFAS through food and water, and by inhaling dust. Since PFAS accumulate in the blood after a long period of exposure and their clearance is slow, even relatively low PFAS concentrations in the drinking water can be associated with substantial increases in blood serum levels.[11]

Water can transport these chemicals, and humans, birds, and fish also help transport PFAS. A decade ago, researchers tracked the contribution of water, diet, air, and other sources for various exposure scenarios to PFOA. What they reported was that when drinking water concentrations of PFOA are high, the ingestion of contaminated water is the predominant source of chemical exposure.

In 2016, EPA proposed a lifetime health advisory level for PFOS and PFOA of 70 ppt in drinking water.[12] In 2018, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) further lowered the minimum risk levels (MRLs) to 11 ppt for PFOA and 7 ppt for PFOS.[13]

Sixty-six public water systems, serving approximately six million people, had at least one sample above EPA’s health advisory of 70 ppt.

As concerning as the EPA data are, it dramatically underestimates how many drinking water sources are contaminated by PFAS. This is because the lowest levels of these chemicals that are required to be reported to EPA (10−90 ppt) were very high compared to the drinking water limit (1 ppt) suggested by studies, meaning that even if PFAS were detected at lower levels, they are not required to be reported to EPA. Moreover, EPA only required testing for 6 PFAS out of the estimated 5,000 PFAS.[14]

What Is The Status Of Cleanup At Military Installations?

Costs arising from PFAS exposure are high, with water-related cleanup cost estimates going higher than $2 billion across all U.S. military installations. Although this is not a shy sum, it may be underestimated, depending on the health effects linked to the exposure that were included in the reports.

DOD reported providing bottled water or other alternate water supplies and installing treatment systems at some of the affected military locations.

Comprehensive reports on cleanup costs for these sites have to include future health care for veterans or service members affected by the contaminated water. It is a priority to make sure veterans who have service-connected illnesses have them recognized by the Department of Veterans Affairs and get the benefits they are owed.

Also, PFAS affect ecosystems and generate costs that are currently difficult to assess through the need for remediation of polluted soil and water.

Currently, the use of AFFF in training at military facilities has largely been banned but persists in fighting actual aviation fire emergencies. When AFFF is used, DOD treats the site as spill contamination. However, it is not clear if the use of the foam in training aboard Navy ships has similarly been banned, as information from the DOD seems to indicate AFFF is still in use.[15]

Environmental Litigation Group P.C. is a national community toxic exposure law firm with offices in Birmingham, AL, and Washington D.C.

[1] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2020. Basic Information on PFAS February 2020, https://www.epa.gov/pfas/basic-information-pfas

[2] U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2018. Drinking Water: Status of DOD Efforts to Address Drinking Water Contaminants Used in Firefighting Foam, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-18-700t

[3] The Environmental Working Group, 2020. PFAS Contamination in the U.S., https://www.ewg.org/interactive-maps/2019_pfas_contamination/map/

[4] Association of Defense Communities, 2019. Robert McMahon, Assistant Defense Secretary for Sustainment Submits Resignation, Departing DOD Nov. 22, https://defensecommunities.org/2019/10/robert-mcmahon-assistant-defense-secretary-for-sustainment-submits-resignation-departing-dod-nov-22-2/

[5] U.S. Dept. of Defence, 2019. DOD Media Roundtable on the PFAS Task Force, https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Transcripts/Transcript/Article/1960674/dod-media-roundtable-on-the-pfas-task-force/

[6] The National Guard Association of the United States, 2019. PFAS Cleanup Costs at Military Installations Continue to Rise, https://www.ngaus.org/about-ngaus/newsroom/pfas-cleanup-costs-military-installations-continue-rise

[7] The Environmental Working Group, 2019. PFAS Detections on U.S. army bases, 2016–2019, https://cdn3.ewg.org/sites/default/files/u352/EWG_PFASTable-Army_C01.pdf?_ga=2.190009771.143307376.1582094181-2123403683.1582094181

[8] Barlow C and Boyd C, 219. PFAS Toxicology - What is Driving the Variation in Drinking Water Standards?, https://www.ct.gov/deep/lib/deep/pfastaskforce/hhc_barlow_boyd_kemp_hoppe_parr_-_2019_pfas_toxicology.pdf

[9] US National Toxicology Program, 2016, Toxicological Profile for Perfluoroalkyls, https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp.asp?id=1117&tid=237; C8 Health Project Reports, 2012. C8 Science Panel Website, http://www.c8sciencepanel.org/prob_link.html

[10] Vestergren R and Cousins IT, 2009. Tracking the pathways of human exposure to perfluorocarboxylates, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/es900228k

[11] Post GB, et al., 2012. Perfluoroocantoic acid (PFOA), an emerging drinking water contaminant: A critical review of recent literature, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22560884

[12] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Lifetime Health Advisories and Health Effects Support Documents for Perfluorooctanoic Acid and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate, https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-05/documents/pfoapfosprepub508.pdf

[13] Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, 2018. Toxicological Profile for Perfluoroalkyls: Draft for Public Comment, https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp200.pdf

[14] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2012. Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule, https://www.epa.gov/dwucmr/third-unregulated-contaminant-monitoring-rule

[15] U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, 2020. Aqueous Film-Forming Foam, https://www.nrl.navy.mil/accomplishments/materials/aqueous-film-foam