Tips For Training Today's Operator — And Making It Stick

By Jeff Berlin, senior project engineer and Steve Walker, principal operations specialist, Carollo Engineers

Introducing three training trends that improve operators’ understanding and plant performance

Three emerging educational trends are gaining popularity as means to improve the training experience and information retention of operators. They are adult learning research, the use of technology, and flipped classrooms. Applying these lessons to professional development and operator training is important to the continued success of the water and wastewater industry.

Adult Learning

Most of our experience with learning comes from our own schooling. However, research has shown that adults learn much differently than children, separating the studies of andragogy (Greek for adult learning) from pedagogy (child learning). The lessons show that adult learning styles require changes in the way training is prepared and delivered. Malcolm Knowles, author of The Adult Learner and respected leader in the field of adult learning, offers six key points which serve both as guidelines to lesson planning and as explanations of potential barriers to retained learning:

- Adults need to know why they should learn something.

- Adults need to be self-directing.

- Adults have greater volume and depth of experiences.

- Adults become ready to learn only when life situations demand it.

- Adults have a task-centered orientation focusing on how to use the information.

- Adults need to perceive benefits to themselves.

These six keys can be boiled down to the adult learner’s core questions:

- Why do I care?

- How do I use it?

Well-designed operator training programs take these questions into account when structuring both the training agenda and materials presented. This can be done by clearly defining the purpose and context of the training material and then building upon the trainees’ experiences and daily tasks to add value (and motivation) to their learning. The purpose of a training session should be to grab the attention and interest of attendees in a way that makes them retain the information conveyed and immediately begin considering reasonable means of applying the information to their real-world experiences. The context of the training serves to focus the learning on those potential applications. One way to define context is by “following the flow” through a treatment plant and highlighting flow paths, key equipment, and interactions. Figure 1 shows an example of location context. A “parking lot” where information, references, or key questions are stored to the side of the main lesson can help anchor lessons to the purpose of the training.

Use Of Technology

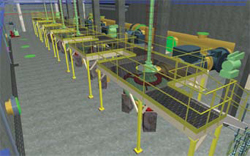

Traditional methods of knowledge transfer can be misapplied to today’s workforce. Millennials grew up with instant access to electronic information. The traditional use of printed references and droning lectures do not dovetail with expectations for rapid uptake and easy access. Therefore, information must be delivered in graphical form, with links to detailed and interactive information. “Flying” through a 3D CAD model is a great way to grab attention, as shown in Figure 2.

Successful training presentations use methods and styles that mimic the way information is presented today, such as pop-ups or running bars. Rather than showing updated scores, these pop-ups provide elemental or crucial knowledge nuggets. Animated calculations can demonstrate the correct techniques to building and solving the algebraic or geometric equations used in daily plant optimization. Dashboards that graphically demonst rate process performance indicators and their expected operating ranges provide realworld feedback to the situations operators may face. A good example of these approaches is a live look at the facility’s online O&M manual, as shown in Figure 3.

Successful training presentations use methods and styles that mimic the way information is presented today, such as pop-ups or running bars. Rather than showing updated scores, these pop-ups provide elemental or crucial knowledge nuggets. Animated calculations can demonstrate the correct techniques to building and solving the algebraic or geometric equations used in daily plant optimization. Dashboards that graphically demonst rate process performance indicators and their expected operating ranges provide realworld feedback to the situations operators may face. A good example of these approaches is a live look at the facility’s online O&M manual, as shown in Figure 3.

One roadblock is the base language that engineers and operators speak. From process models to drawings, engineers communicate in formats that are novel to operators. On the flip side, operators communicate their challenges, daily tasks, and operating procedures in ways that can befuddle the engineer. Fundamental to any successful training interaction is bridging this divide so that both parties are fully understood. Every plant has its own language, where names or numbers are surrogates for the engineering term or project. It is incumbent on the trainer to ask about, understand, and then incorporate the jargon used by the plant’s staff. Not only does this help cement the new knowledge, but it also shows that the trainer has taken the initiative to learn the audience, gaining real credibility.

One roadblock is the base language that engineers and operators speak. From process models to drawings, engineers communicate in formats that are novel to operators. On the flip side, operators communicate their challenges, daily tasks, and operating procedures in ways that can befuddle the engineer. Fundamental to any successful training interaction is bridging this divide so that both parties are fully understood. Every plant has its own language, where names or numbers are surrogates for the engineering term or project. It is incumbent on the trainer to ask about, understand, and then incorporate the jargon used by the plant’s staff. Not only does this help cement the new knowledge, but it also shows that the trainer has taken the initiative to learn the audience, gaining real credibility.

Understanding how this knowledge affects working life addresses one of Knowles’ points. Helping the audience visualize its application using scenarios that mimic real situations can drive the information deeper into the brain by using additional senses besides hearing. Asking questions that draw the trainee into the scenario establishes a lesson that can be relived when the situation happens.

Flipped Classrooms

Secondary education, mainly high schools and colleges, are implementing new teaching strategies. Flipped classrooms reverse the traditional lecture model. Instead of spending limited contact time delivering content, the class period is used for hands-on activities, interactive quizzes, and collaborative “home” work. Time outside of class is devoted to traditional lecture materials, such as recorded lectures on YouTube. This concept is gaining national exposure (Miller, 2013).

Colleges have used interactive classrooms, in which each student has a clicker to answer questions from the professor. Realtime results offer feedback on knowledge transfer. You may have seen similar approaches via text message polls at conferences. Interestingly, real-time answers show significant improvement if students are asked to discuss their thoughts with those around them. Such collaboration is at the heart of adult learning.

So how do we apply these concepts to our industry, where hands-on engagement drawing on operators’ experiences is rare? Some ideas on how to do this are:

- Start training with introductions, asking participants’ roles and responsibilities.

- Regularly ask questions, using quizzes or polls.

- Ask participants to discuss concepts with their neighbors.

- Incorporate technology, such as a link to online O&M manuals.

- Sandwich classroom time into field visits.

Conclusion

When applied to operator training within our industry, these emerging educational trends have the potential to improve interest, engagement, and retention. This will result in motivated, more knowledgeable operators and more efficient water treatment facilities overall. We can use lessons from adult learning research to flip the classroom and take advantage of new technological resources. All-in-all, training is more effective when it:

- Clearly defines purpose and context;

- Relates to the operator’s daily experience; and

- Encourages trainee participation and engagement.

Quality operator training is a significant investment of time and money. However, a well-planned training program will pay off in operator understanding, which translates to improved plant performance.

References

Malcolm S. Knowles, E. F. (2011). The Adult Learner, Seventh Edition. Oxford, UK: Elsevier, Inc.

Miller, J. (August 2013). Flipped Out. Spirit (Southwest Airlines Magazine), pp. 73-81.

Jeff Berlin is a senior project engineer for Carollo Engineers, with more than 12 years of experience in wastewater treatment planning, design, and construction. Berlin is responsible for training operators in a 114-MGD secondary treatment facility in Denver, CO.

Jeff Berlin is a senior project engineer for Carollo Engineers, with more than 12 years of experience in wastewater treatment planning, design, and construction. Berlin is responsible for training operators in a 114-MGD secondary treatment facility in Denver, CO.

Steve Walker is the principal operations specialist for Carollo Engineers, with more than 29 years of experience. Prior to working for Carollo, Walker was the treatment superintendent for a 185-MGD facility in Denver, CO. He holds top level wastewater certifications in Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, and Arizona, and serves on the State of Colorado’s Water and Wastewater Operators Certification Board. Walker earned a BS in Technical and Industrial Administration and received the William D. Hatfield Award for outstanding performance and professionalism in the operation of a wastewater treatment facility.

Steve Walker is the principal operations specialist for Carollo Engineers, with more than 29 years of experience. Prior to working for Carollo, Walker was the treatment superintendent for a 185-MGD facility in Denver, CO. He holds top level wastewater certifications in Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, and Arizona, and serves on the State of Colorado’s Water and Wastewater Operators Certification Board. Walker earned a BS in Technical and Industrial Administration and received the William D. Hatfield Award for outstanding performance and professionalism in the operation of a wastewater treatment facility.