The Potential Of Customized 3D-Printed Membranes

Researchers have begun to explore the idea of 3D printing as a way to manufacture membranes. What could the cutting-edge technology mean for water and wastewater treatment?

3D printing appears to be the next horizon in production. It is a process in which a computer directs successive layers of material to accrue and form an inputted design. Traditional manufacturing, which relies on molds and fixed processes, tends to create the same object over and over. In 3D printing, because nearly any design can be put into the computer and then executed, resulting objects can be of almost any shape and highly specified for a given purpose. This gives manufacturers much more control over the designs of their products and the power to meet a given need nearly on the spot.

3D printing has been utilized by General Motors for the creation of automotive parts, by architects to create unique building models, and even by medical researchers to create prosthetics and artificial organs. Recently, a research project was conducted to find out what 3D printing could lend to the creation of treatment membranes.

The process offers a chance to customize membranes to specific influents, to target certain contaminants of concern, and to react to emergency situations. 3D printing is a way to create a more specific membrane to solve treatment plant needs.

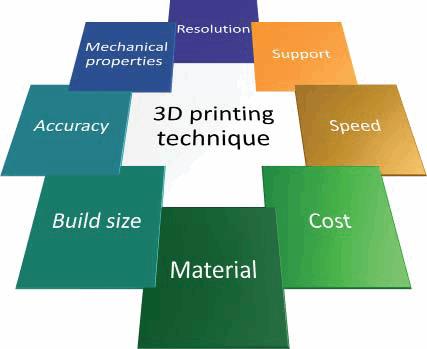

Key properties of 3D printing techniques (Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0)

“The need was to find a way of controlling the architecture of membrane microstructures in a predictable way so that the performance of the membranes can be predicted and controlled from the outset of designing the membranes,” said Dr. Darrell Patterson, the director for the Centre for Advanced Separations Engineering at the University of Bath, and an author of the study. “Currently, the main [production] methods of polymer membrane formation do not allow for this.”

By getting more specific with a membrane’s shape, treatment plants could do more within the same footprint. “A shaped membrane that can have a maximum surface area to increase the practical membrane surface-area-to-volume ratio, to increase membrane area in the same membrane holder, for example, could improve on the current flat sheet and hollow fiber membrane shapes,” Patterson said. “3D printing would allow complete control over the design and fabrication of such shapes, which currently is not possible.”

The authors of the study explored how 3D printing technology could be applied to membrane engineering. Over the past 10 years, they say, 3D printing has reached a point where it offers the control, resolution, and precision that allows for membrane fabrication. It also allows for the micro- and macro-structure of the membrane to be designed and built at once, offering the potential for integrated design between the materials used and their purposes. Tailormade membranes could be designed to keep particles from fouling the surface and, one day, could be made on-site to respond to specific contamination problems.

“We think that shaped membranes could help reduce fouling and increase the area of the membrane that can be used in a typical membrane plant,” said Patterson. “Additionally, the on-site production of membranes that are tailored to the separations needed would also be possible, allowing a quicker response and unprecedented changes in water and wastewater composition.”

There are, however, still limitations on the use of this technology to build treatment membranes. Primarily, 3D printers aren’t yet equipped to produce them.

“3D-printed membranes are currently limited by the resolution and build size of the current 3D printers,” said Patterson. “We really are waiting for the 3D printing technology to catch up with our ambitions to allow 3D printing to become a realistic and cost-effective membrane production technology.”

That being said, the researchers are so enthusiastic about the potential for 3D printers to revolutionize water and wastewater treatment that they don’t want their thinking to be stunted by what’s currently possible. Patterson mentioned the possibility of one day printing the membrane and module all in one piece, but out of different materials, creating a membrane with a range of different pores and surface structures to optimize flux. The membrane then becomes capable of selectively removing and recovering the molecules and particles that cause fouling and utilizing materials that don’t age, to increase the lifespan of a membrane.

“We don’t want to be limited to what is currently available in the membrane market,” said Patterson. “We want to be able to do things that are not currently possible. … If these can be realized, then 3D printing could potentially become the go-to technology for membrane fabrication in the future. Given the rate of development of 3D printers, we would estimate that at least some of this will be possible within the next five to 10 years.”

About The Author

Peter Chawaga is the associate editor for Water Online. He creates and manages engaging and relevant content on a variety of water and wastewater industry topics. Chawaga has worked as a reporter and editor in newsrooms throughout the country and holds a bachelor’s degree in English and a minor in journalism. He can be reached at pchawaga@wateronline.com.

Peter Chawaga is the associate editor for Water Online. He creates and manages engaging and relevant content on a variety of water and wastewater industry topics. Chawaga has worked as a reporter and editor in newsrooms throughout the country and holds a bachelor’s degree in English and a minor in journalism. He can be reached at pchawaga@wateronline.com.