The Full-Bodied Approach To Odor Control

One of the prevalent problems at wastewater treatment plants that continues to escape solution does not involve crumbling infrastructure or newly-emerging contaminants.

Yet it is a problem that directly affects the public, that unfairly inundates wastewater operations with negative attention. It is the persistent issue of foul odors.

A natural byproduct of the waste and chemical agents found at these plants, foul odors often reach neighbors and can cause wastewater operators many headaches as they try to solve them. Their root often comes from a combination of smells, each with its own source and requirements for removal. It can be an overwhelming problem to solve.

To offer a helping hand, researchers from technology provider CH2M and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) joined forces and developed a holistic approach. The research was motivated by the fact that at many plants, solving for the most typical odor contributor was not enough.

“We found that several wastewater treatment plants were still having community nuisance odor impacts, even after treating traditional odorants like hydrogen sulfide,” said Jay Witherspoon, a CH2M senior fellow technologist and lead of the research team. “Typically, hydrogen sulfide is the predominate odorant that causes nuisance odor impacts to the community. However, at these wastewater treatment plants, other non-hydrogen sulfide compounds were causing these community impacts.”

The research team worked with the Orange County Sanitation District (OCSD) and the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD) to fine-tune its approach.

“At OSCD, the main odorant was hydrogen sulfide, which was targeted and removed effectively, but it still had a community odor nuisance issue,” Witherspoon said. “For PWD, it had a canned-corn odor that was fleeting, but at levels that caused a nuisance odor impact.”

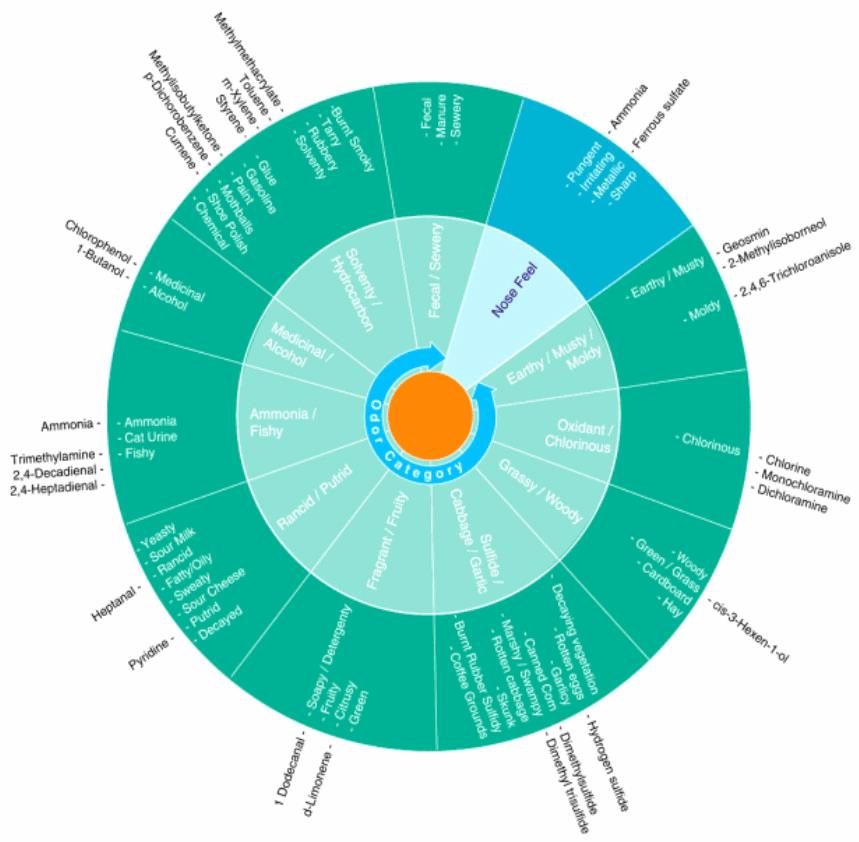

To get a better handle on what, exactly, was contributing to those smells, researchers utilized UCLA’s odor profile method. They approached neighbors with an “odor wheel” that would allow them to match their understanding of the smell (rotten eggs or canned corn) to its chemical contributor (hydrogen sulfide or dimethyl sulfide).

“The odor wheel was developed by UCLA, with fine-tuning from PWD and OCSD,” said Witherspoon. “The outer wheel has the chemicals that are associated with the odors described in the inter-wheel spokes. The public can use the simple odor descriptors in the inter-wheel to describe the odors they smell and the team then knows the chemical type of odorant and how to effectively remove it to below nuisance levels.”

Once the odors were identified, the researchers used an air dispersion model to quantify their impact and “electronic noses” and other handheld devices to capture them. It then analyzed samples in laboratories using a mass spectrometer and other detection devices, and had a human panel determine how strong and offensive each smell would be to neighbors of the plants.

Once the team got a full handle on what was causing each smell and how powerful it really was, it could determine what combination of chemicals, scrubbers, and biofilters were necessary to control it.

Of course, the average wastewater utility won’t be able to send samples out for laboratory testing, much less convene a panel of human smellers to offer their expertise. Still, the odor wheel seems to be a relatively affordable and neighbor-friendly way of identifying the source of odor issues.

“Use the odor wheel to screen the chemical type of odors being smelled, then focus a removal program on those chemicals,” Witherspoon said.

Then, when it comes to solving for the odors that are identified, it is a matter of identifying and investing in the necessary technology or technologies.

“Proven and innovative technologies are available for the removal of a full suite of odorants seen at wastewater treatment plants,” said Witherspoon. “Depending on the odorant, the right technology solution can be found. One technology usually can’t address all odorants seen at the plant.”

Finally, Witherspoon has one piece of advice for the treatment plants out there that are looking to solve their odor issues.

“Don’t think that once you’ve treated your hydrogen sulfide issue that you won’t have any additional odors that cause a nuisance to your community,” he said.