'Super' Advice From Philadelphia's Water Commissioner

By Kevin Westerling,

@KevinOnWater

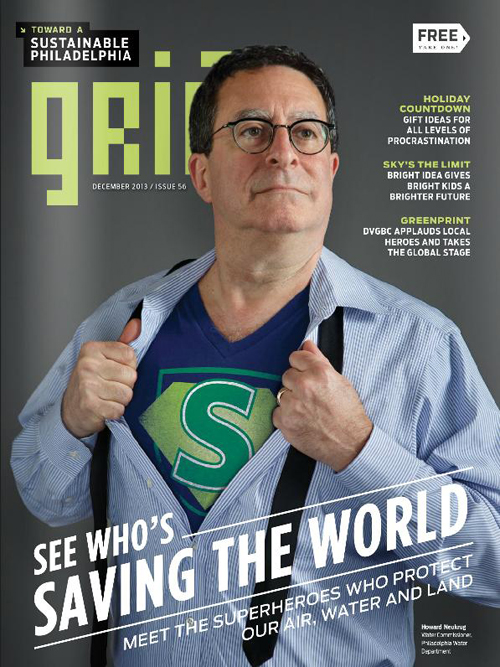

This Q&A is longer than my usual for Water Online, but the exception is warranted. It's not often that you have the opportunity to talk to a 'superhero' of sustainability. That's how Howard Neukrug, commissioner of the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD), is viewed in these parts (I'm from Philly), as evidenced by this local magazine cover…

Nationally, Neukrug's work is lauded and emulated. Philadelphia's Green City, Clean Waters program is a model of stormwater management, and also a template for urban beautification and revitalization. In addition to receiving numerous accolades for water management and pollution prevention — Green City, Clean Waters was started in 2011 to reduce Philadelphia's combined sewer overflows (CSOs) — Neukrug was recently granted the 2015 Arbor Day Award for PWD’s greening of Philadelphia.

When you sit and talk to such a figure in the water industry, you leave no stone unturned. What follows, then, is a wide-ranging interview on the Philadelphia story and its implications, the nationwide state of sustainability, common municipal struggles to be overcome, and the future outlook for the water/wastewater industry. I pared down our conversation to 10 key topics, and let Howard elaborate from his unique perspective as a water leader ... and superhero.

Can any size utility pull off an ambitious program such as Green City, Clean Waters, and what’s the starting point?

Any size city can do it, but not any city can do it.

Collaboration is incredibly important, and sometimes incredibly hard, because every agency, every organization — whether government or nonprofit or private — has their own set of missions and schedules and budgets. It gets hard to bring all these things together and work across those missions and budgets and find ways to leverage and cooperate. But for every city, it could be a great way to both clean up your water body cost effectively, and also sustain your cities.

Instead of spending money underground to increase sewer capacity, spend the money aboveground to reduce the rainwater that becomes “waste” when we direct it into the sewer system.

Of course planting one tree is not going to change the world. But planting an urban forest begins to make that change.

Can green infrastructure potentially replace what would otherwise be a gray infrastructure sewer project?

Yes, if you have the space and conditions to do it. Philadelphia is looking to combine green with gray solutions, so that the gray solutions are not as massive. You spend some of the [would-be] gray dollars on the surface, looking at green solutions to leverage with the other utilities, developers, city departments, schoolyards — anywhere you can find a way to manage water before it reaches the sewer. This is an approach that takes advantage of the incredible sewer infrastructure investment made over the past century or two.

That’s not to say that our sewers and our treatment facilities don’t need to be expanded, or that we can get away with never making additions or expansions. We need both. Any good city manager is looking to integrate all the capital projects that need to occur within their cities, and to do it in a coordinated fashion so that you’re maximizing the dollars that you spend and leveraging everything you can.

In another year or so, we’ll have about 1,000 acres of land where the first inch of a rainstorm will no longer go to our sewer system. That’s a pretty incredible number. It’s just the start of an evolution of how you manage a city. But right now, cities are designed at a gradient — it starts at the rooftop, goes down the drain, onto the sidewalk and streets, and into the sewer inlet. Cities are designed to remove rainwater as quickly as possible.

By turning rainwater into a valuable commodity, you start realizing that maybe you shouldn’t be wasting it. Maybe we should be reusing it, recycling it, infiltrating it, and managing that rainwater.

There are facilities that collect the rainwater and put it into a cistern and use it for toilets or landscaping. We’re seeing the investment in rainwater as a resource growing more and more. We’re seeing it in certain industries where, if we can start working with the industry, we can show them how they can buy less water from us for their processes. And by capturing their own rainwater, they’re having less impact on our sewer system.

[It results in] less overflow of sewage, which has a value to it, and also less need to build larger infrastructure. Losing revenue is not an easy thing for a utility manager in any circumstance, but what we’re looking at is balancing our revenues with our infrastructure system and being able to maintain the system that we have and not continue to need to grow our system.

When it comes to infrastructure improvement, whether green or gray, can utilities look to the federal government for funding, or does it need to be generated locally?

Unfortunately, unlike the highway industry, where surface transportation funding is about 85 percent federal and 15 percent local, I would say over 99 percent of the funding in the water industry comes from the ratepayers’ water and sewer bills, and there is little to no federal funding available for us. [Editor’s note: Neukrug cites the above figures as estimates, for illustrative purposes.]

There is limited money available at the local, state, and federal levels, and we need to come together and figure out how to best expend the limited dollars we have. What’s great about Green Cities, Clean Waters for the City of Philadelphia is that it moves us in that direction. We have a very large low-income community, and affordability of rates is a very big issue. We’re exploring a low-income water rate, which in some sense is against our philosophy based upon true cost of service, but we have to make sure that water is affordable to all of our customers. It’s true for just about anything: determine your goal and figure out how to get there by integrating and coordinating your activities across the board.

Do you think public-private partnerships, performance contracting, and alternative delivery methods for capital projects are good solutions to municipal financing issues?

Public-private partnerships are critical for piloting innovation. Working with private funding to test out equipment and technologies from third parties really does take partnership and trust. It’s a lot of work to even come up with the legal agreements on how you work together and the financial arrangements, not to mention the technical issues, but it’s something that’s very worthwhile. I know we’re doing it in Philadelphia on a number of different fronts. We’re also working with a number of groups that are looking at innovators on a regional basis, including TAG [Isle Utilities’ Technology Approval Group]. We all get together and take our most creative thinkers. We’re always looking for new opportunities and wondering what the next big thing to try is.

But for the average utility manager, it’s hard to find the time to investigate new projects and new types of systems. We are a conservative organization as a whole, but I think you also find that there are quite a few very innovative and forward-thinking utility managers throughout the country, who, if given the right opportunity and if presented correctly, will be happy to explore new technologies.

How can new technologies be leveraged for more sustainable water and wastewater operations?

These new concepts of what some people are calling ‘utilities of the future’ and what I refer to as ‘resource recovery and efficiency facilities’ … there’s a big push [for them] in Philadelphia. We’re certainly looking at how we can increase the efficiency of our facilities and make them more energy-independent, and how we can recover the resources in wastewater.

PWD’s Biogas Cogeneration Facility at the Northeast Water Pollution Control Plant

There’s an incredible, huge potential for energy production and, at the very least, for what we call a ‘net-zero energy facility.’ It doesn’t come free; you have to spend money to plan and to design, build, and operate such facilities. But as we look towards the future and how energy prices will fluctuate, making your facilities energy-independent or increasing the portfolio of investment on how you get your energy is going to be a critical issue for water plants.

One of the big things that we’re looking at is the heat from sewage. If we can extract the heat from the sewer water and use that for heating and cooling HVAC systems for industries and facilities near our wastewater plants, that’s a very large resource that we can give back to the community, and perhaps save money and reduce the variation of the temperature of the water going into the rivers and streams.

Do you have a specific plan or recommendations to account for climate-change impact?

A lot of people are still arguing if there is climate change occurring. But it’s very clear that we’re having bouts of extreme weather that have been occurring over the last decade-plus. Whether that’s going to continue or not, I don’t know.

But I think it has alerted utility managers to the point where we recognize the need to begin looking at issues of sea-level rise and hurricanes, as well as similar but different issues around security — looking at our facilities and making sure they are sustainable and resilient for the next century.

There aren’t a lot of options. Given the climate that we have — even the one we have now versus the one that we may have in the future — we only have a couple of choices: keep water out of the sewer or make the sewer bigger.

What about maintaining the existing, aging pipe system? How does Philadelphia approach repair and replacement?

We’ve created a risk/consequence modeling system where we’re looking at the age and quality of the pipes and analyzing and identifying which pipes need to be replaced first.

That being said, the next thing you need is money. It’s very different today than it was 100 years ago, because 100 years ago, when the City of Philadelphia built a mile of pipe, we had a mile of new customers.

Today, we’re placing a mile of pipe and we’re lucky if we have a mile of customers. Pipes are being replaced where there might be some vacant housing or underutilized properties. It’s a very, very costly operation.

We recently increased the amount of pipe that we’re replacing — we’re now replacing about 1 percent of the total water service system- annually — and we’re looking at the potential of increasing that further. One of my goals would be to reduce the number of main breaks in half over the next couple of decades. It’s going to take another $600 million, and I’m wondering: Is that a good investment?

It really comes down to recognition of the impact of these water main breaks. Many of the breaks in Philadelphia have little impact — there’s just water on the street and we go out and make repairs. Others are catastrophic and have great impact on homeowners, businesses, and traffic. It’s a business decision that every utility in the country makes, about how much pipe to replace. The best utility manager replaces their pipe the day before it breaks.

The problem is, of course, you don’t know when that date is. You want to err on the side of conservatism, but you don’t want to replace a pipe that still has 50 years in it. You may want to replace a pipe that has 20 years in it. The challenge is to balance technology — the science of knowing which pipes to replace — alongside risk and consequence, the priorities of your city and its managers, and how much money you have.

We all have to manage on different terms of prioritizing our dollars and looking at the quality-of-life benefit of everything that we’re doing with limited resources.

Does PWD employ advanced metering infrastructure (AMI)? Is that part of the leak-detection/asset management plan?

We were one of the first utilities in the country to deploy an automatic meter reading (AMR) system, in the 1990s. Once you have that system in, you’re dealing with lifecycle span. We’re now looking at an eventual replacement for our AMR system, and we’ll be investigating that over the next couple of years. AMI would be another large capital expense, but may be a necessary expense. I’m looking forward to seeing what the industry has to provide us in that area.

In terms of leakage and AMI, there are concepts that I am really excited about, such as being able to conserve water in people’s homes by identifying leaks and letting them know about them before their next water bill gives them a jolt.

In terms of our distribution system, we do have a leak-detection program now. It’s not connected with our AMR system. We inspect one-third of our distribution system each year, and we identify leakage and repair it. That work can always be done. But, again, we’re balancing a list of priorities, whether it be flooding, sewage, water main breaks, or leakage.

How have extreme rain events affected PWD operations?

Well, when I go in front of some residents who are rightfully angry because their basements have been flooded and I tell them this was a 400-year storm, they start laughing at me.

It is possible to have a number of 400-year or 100-year storms in a row … but it does suggest a problem related to stationarity, or the assumption of stationary data. The 100-year storm is a number that’s made from looking at 100 years’ worth of rain data and predicting the likelihood of a future event based upon that data. The concept of ‘where we’ve been is going to predict where we’re going’ may no longer hold.

But with limited resources and so many needs, how do you prioritize a change for storm events that may or may not actually occur? Hopefully we’ve made good, rational management decisions on how to balance those things. Of course we would always like to do more, but first you need the resources and then you have to determine the cost and efficiency of making those changes.

You have said that change can come from either crisis or leadership. In your opinion, which will be the bigger driver for U.S. municipalities going forward?

I’m seeing a lot of leadership occurring at the city level, throughout the U.S., and I’m also encouraged by the professional organizations in the water and wastewater industry — where they’re headed and the professional culture they’re providing. Unfortunately, we’re still getting hit with crisis.

We have a particular crisis in Philadelphia with the retirement of both blue- and white-collar workers. We’re losing a lot of expertise and knowledge, and our crisis at the moment is how to transfer that knowledge, as well as who you’re transferring it to. Finding that mid-level manager, those with 15 to 25 years’ experience, seems to be a difficult spot.

At the earlier stages, we’re seeing an incredible level of young scientists and engineers, planners, and finance folks who are coming into this business and are passionate about changing the world and making improvements in water systems. They are extremely bright, extremely focused, and look like people who are going to stay in the industry for a while.

I’m very nervous about the short-term changeover, and very excited about the future.

As for which one — crisis or leadership — will drive change, I’m not sure it’s an either/or anymore. I’m seeing crises occur without any change, and I’m seeing good leadership without any change. Perhaps it’s a combination, but you need to be ready to implement change. Crisis can help … but leadership is absolutely required.