Reclaiming Water: The Rise Of Wastewater Recycling To Meet Potable Water Needs

By Kiera Outlaw, IBISWorld Procurement Research Analyst

There’s roughly 32 billion gallons of municipal wastewater produced every day in the U.S., but according to a 2012 water reuse report by the U.S. EPA, less than 10 percent of that water is recycled. While drought and population growth is pushing water resources to their natural limits, cities around the world are seeking out sustainable alternatives to meet their future water needs. As global fears of water scarcity escalate, IBISWorld expects a rise in the development of water recycling programs. As a result, demand for water treatment-related goods and services will increase and push their corresponding prices up, which could raise budgetary concerns later on.

Singapore is a world-class leader in water recycling and total water management, having spent the better part of four decades developing its total water management system, including turning wastewater into drinking water. Additionally, San Diego approved an innovative $3.5 billion plan to develop a sewage purification system in 2014, catapulting the city onto the global stage as a wastewater recycling leader. While Singapore and San Diego face similar water scarcity issues, their solutions vary and serve as great models for other countries and cities around the world looking to meet their drinking water needs through a recycling program.

Tried and True: Singapore and NEWater

Water is precious, but it is exceptionally dear in Singapore. While the country gets ample rain, there are no natural water storage facilities, such as groundwater aquifers, soil water, or natural wetlands. As a result, Singapore developed water supply agreements with its largest and closest neighbor, Malaysia, which date back as far as 1927. While the agreements provide Singapore with the water it needs, the arrangements are expensive as well as politically and financially unsustainable. Thus, the Singaporean government has gone to work developing a more sustainable and long-term water management plan ahead of the expiry of two longstanding supply agreements with Malaysia, one in 2011 and the other in 2061.

To reduce its reliance on Malaysian water imports, Singapore developed its Four Tap Strategy. The first two taps were devoted to building infrastructure, such as water reservoirs and ensuring favorable agreements for water imports. The development of its greatest water management achievement, NEWater, was the third tap, and saw Singapore open its first water reuse plant in 2002. The fourth tap was the opening of the country’s first desalination plant in 2005.

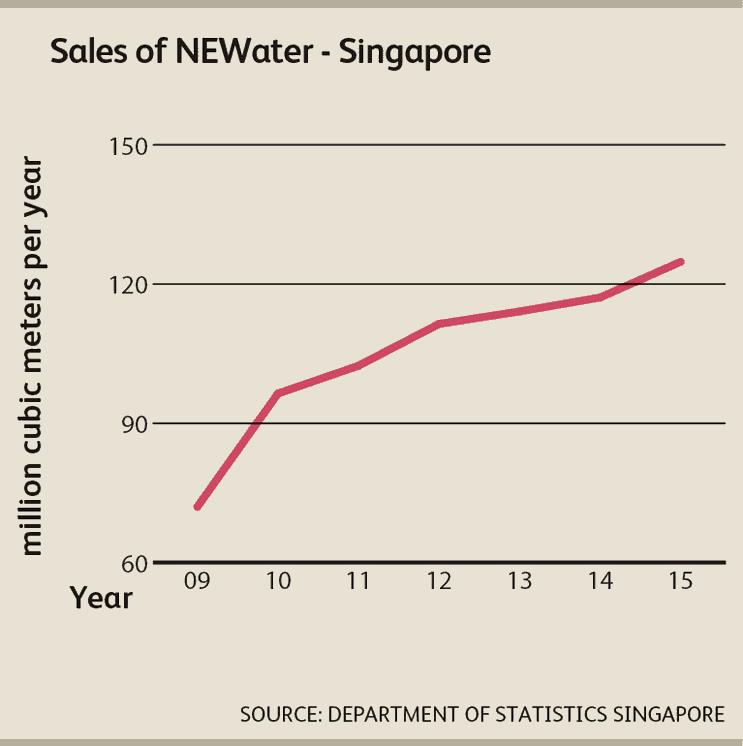

The development of NEWater has become the global standard in reclaiming wastewater to meet standards suitable for human consumption. Singapore invested a lot of time and money into researching and developing the processes that go into reclaiming the water. The NEWater process purifies the wastewater using dual-membrane and UV technologies in addition to the conventional water treatment process. To ensure acceptance from the community and the success of the program, Singapore embarked on an educational campaign to dispel the rumors surrounding the “toilet to tap” moniker. Singapore has continually worked toward reducing the costs of NEWater by creating more efficient processes and opening more water reuse plants. Currently, there are four operational plants.

San Diego’s New Approach to an Old Idea

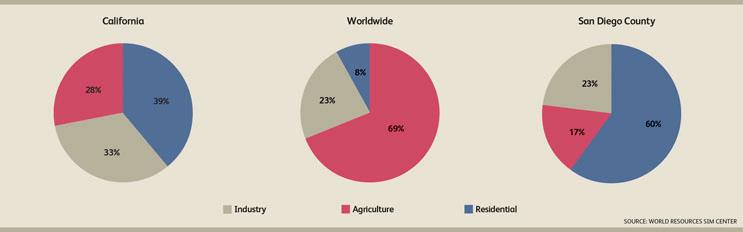

San Diego is going about its water recycling process differently. While Singapore had to build its reservoirs, San Diego has the San Vicente Reservoir at its disposal. However, California state regulations require recycled water to be diverted to underground basins before entering the local water supply. San Diego, however, does not have access to underground basins. Instead, the city pitched the idea to recycle wastewater using its reservoirs. The recently approved use of the reservoir will essentially change the rulebook on water recycling in the state of California, as regulators and city officials will need to work together to establish new regulations to ensure water safety.

San Diego’s use of city reservoirs, as opposed to underground basins, will require the city to treat the water more aggressively, borrowing processes already in place in Singapore such as microfiltration, ultrafiltration, reverse osmosis, UV technologies, and traditional water treatment processes like hydrogen peroxide. San Diego’s process of water treatment and purification needs to be intense because the use of reservoirs reduces the retention time of the wastewater, during which the purified water can mix with rain and imported water. San Diego has an opportunity to become a model for other cities and nations that lack sufficient underground basins for their water recycling programs. To sway community opinion, San Diego may have to take a page out of Singapore’s book and embark on an educational campaign on the process, particularly as water recycled using a reservoir, rather than an underground basin, will be a tougher sell to city residents.

Water Reuse and Higher Input Costs

While Singapore and San Diego are emerging as leaders in the race to secure their future water needs, global fears of water scarcity will not be abated anytime soon. More communities must develop successful, and perhaps similar, water recycling programs to keep pace with anticipated population growth. The implementation of water recycling programs across the country will drive demand and price growth for a number of related goods and services. For example, San Diego’s new project will require a range of water treatment chemicals to ensure that the recycled water meets regulatory standards and is fit for human consumption. Recent trends reflect a rise in water recycling programs, so IBISWorld expects that demand for water treatment chemicals will rise and push prices up at an annualized rate of 0.5 percent in the three years to 2020. Meanwhile, once the purified water is retained, regulators will need to regularly test the water to ensure the purification process has been successful and meets regulatory requirements. In turn, IBISWorld projects that demand for water quality testing services will rise, which will increase demand for water quality testing equipment and cause prices to increase at estimated annualized rates of 1.0 percent and 1.1 percent, respectively, through 2020. It’s reasonable to expect that the rising costs of goods and services associated with the purification process of water recycling will increase overall production costs, which may be another speed bump in improving the community’s perception of drinking reclaimed water.

Nevertheless, demand for water is expected to only grow in the years to come. To meet this rising demand, San Diego plans to have three water recycling facilities up and running by 2035, expected to produce a combined 83 MGD. At first this sounds like a lot of water, but it will only satisfy an estimated one-third of the city’s total water needs. Meanwhile, Singapore will continue to earmark money to continually invest in and develop water research and development centers. The need for countries and cities across the globe to develop long-term, sustainable, and efficient water reuse programsis growing, and both Singapore and San Diego will be excellent models to learn from.