Pandemic Adds New Resiliency Concerns For Water Providers

By Karen Burgi, Jo Ann Jackson, Kevin Laptos, Ed Rectenwald, and Jim Schlaman

A survey reveals what COVID-19 has wrought at utilities, and what actions may be necessary to prepare for future events.

Water utilities historically have delivered clean, dependable water for generations, so reliably that in the U.S., it’s often been taken for granted and considered an expectation. But resilience concerns are growing, given aging infrastructure, population growth, and stresses on existing supplies.

Now, add COVID-19 to that mix — the latest unforeseen event to challenge the industry over the past two decades.

After the September 2001 terrorist attacks, regulators pressed U.S. water providers to address bioterrorism and cybersecurity in their operations. Ensuing worries about climate change have brought into sharper focus threats posed by everything from drought cycles to higher rainfall intensity events, sea-level rise, and its resulting migration of higher-salinity water into groundwater aquifers.

With the pandemic comes an opportunity for the industry to critically rethink its resiliency strategies as the surge of remote working has redistributed water demand from urban centers to the suburbs and beyond, potentially straining those outlying infrastructures with higher peak demands. All the while, managers of utilities have become more isolated as social distancing has limited the number of people who can be in operational centers at any given time, changing and sometimes complicating decision-making procedures.

Already, even as the full sweep of the ongoing pandemic’s impacts on the industry continue to emerge, lessons are being learned, including about how to continue distributing water even with a utility’s workforce more fragmented.

But a vexing question has surfaced: Does COVID-19 mean an inflection point for utilities to now incorporate pandemics into their resilience planning? Is the pandemic driving new concerns around health, safety, and workforce continuity planning? Does this drive financial and capital reprioritization for the tens of thousands of U.S. water utilities, big and small?

The short answer is yes.

Resiliency: The More Contingency Plans, The Better

Without question, the water industry is an asset-intensive, rate-restricted industry that requires informed decision-making to effectively balance capital investment and rising operational expenses with resistance to rate increases. This makes the water sector notoriously complex, variable, and uncertain.

The COVID-19 pandemic amplified that, exposing weaknesses in utilities’ resilience planning — or pressing water providers to finally develop a robust resilience blueprint if they lacked one in the first place.

Consider it a generational opportunity, grounded in the premise that the more contingencies you have planned for, the better.

Water utilities start in small, centralized locations, and grow as the communities they serve expand. Investment typically has gone into keeping up with municipal growth and daily operations.

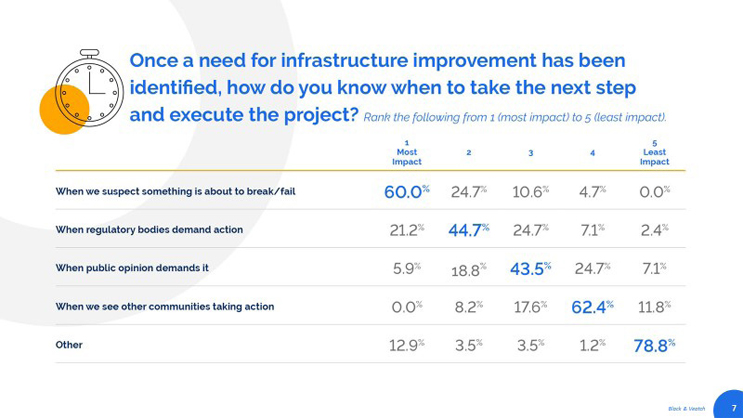

Meanwhile, as the water system grows and grows, the pipes that have been in the ground generally only get attention when they’re close to failure, as illustrated by a survey of hundreds of industry stakeholders for Black & Veatch’s recent 2020 Strategic Directions: Water Report.1 Replacing that pipe is costly and disruptive.

For years, resilience-minded U.S. water utilities designed and planned their infrastructure systems based on certain demand patterns and diurnal peaking factors. In many areas, COVID- 19 has turned those models on their heads, shifting demand to residential areas from urban commercial and industrial (C&I) areas that, in many cases, were disrupted by the pandemic, thereby stressing distribution systems in residential areas that may have infrastructure without enough hydraulic capacity to handle the increases in demands. All the while, formerly bustling urban centers face lower flows and potential water quality concerns.

So far, the issue of changing demand patterns is largely anecdotal, but, for many communities, it has been telling.

Source: Black & Veatch “2020 Strategic Directions: Water Report”

In Wellington, CO, with 6,300 residents, water demand spiked 46 percent in May over the highest total ever recorded for that month, Bob Gowing, the city’s public works director, told the Loveland Reporter-Herald in October. That trend, he added, pressed on through the summer, “easily attributable to more folks staying at home and changing their daily patterns,” straining staff and wastewater systems so much that Wellington ended bulk water sales for construction while limiting its use for irrigation.

What’s perplexing is gauging the permanence of such shifts in water demands — or whether this constitutes the new normal, at least for the coming year or two, as C&I customers continue to rethink the way they do business and, by extension, use water. Given such pandemic-prompted changes, utilities would be wise to assess whether their pumping facilities serving residential areas are undersized and in need of upgrades. Is there a need for additional water storage in those areas? Are there, or will there be, water quality issues in some commercial areas because demand there is now lower, given the dramatic change in the system’s performance?

Without question, it’s a moving target in need of being addressed.

COVID And The Water Utility Workforce

Some utilities already may be ahead of the game in resilience planning, if for no other reason than because of their geographies. In Florida and much of the Gulf Coast, for instance, water utilities may be more capable of weathering such challenges as the pandemic because they already have rigorous resiliency and emergency frameworks in place to mitigate the effects of hurricanes and other extreme wet-weather events.

Source: Black & Veatch “2020 Strategic Directions: Water Report”

More than 80 percent of respondents to Black & Veatch’s recent survey listed natural or man-made disasters as their top resilience concerns. Catastrophic infrastructure failure was a distant second (56 percent), followed by another climate change-related category — extended drought and supply restrictions — at 38 percent.

Such utilities, for example, already may have entrenched “backup” protocols for addressing shifting staffing demands at times when hurricanes force their operations managers to work remotely while sheltered in place. The COVID-19 pandemic may have complicated that, given social distancing directives meant to minimize exposure across the workforce.

In short, utilities would be well-served giving thoughtful deliberation about key questions that, at least recently, have had them scrambling to answer. When it comes to better future-proofing a master plan, how can essential workers be accommodated without compromising services when a sudden event arises? Which employees can work remotely? What precise roles can be done from home?

The America’s Water Infrastructure Act,2 signed into law in 2018, may help provide at least a basic framework to build upon, requiring community water systems serving at least 3,300 people to develop or update risk assessments and emergency response plans.

Matters Of Finances, Investment, And Data

To no one’s surprise, as Black & Veatch’s 2020 Strategic Directions: Water Report pointed out in June, U.S. water utilities have taken an operational and financial hit from the pandemic as some of their biggest clients — C&I users — halted operations and tens of millions of layoffs of U.S. workers stymied the ability of households to pay their utility bills, undercutting revenue and cash flows to water and energy providers. Around the country, water providers suspended water and wastewater shutoffs to delinquent accounts, in both the interest of humanity, and as an affirmation of the importance of water and sanitation in trying to contain the virus.

Industry observers predicted that operators of drinking water, clean water, and water recycling systems faced billions of dollars in lost revenue, fueling the prospect that without taxpayer help, those financial shortfalls could be passed on to water customers in subsequent years and lead to future rate increases.

Regardless, the industry would be wise to creatively find ways to modernize through innovation in strategies, operations, and funding to protect human health and the environment and to empower the economic engine that comes from infrastructure investment.

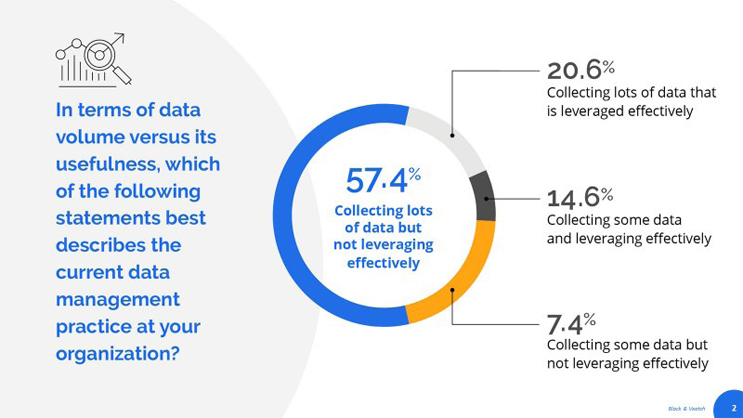

Source: Black & Veatch “2020 Strategic Directions: Water Report”

Even though infrastructure investment has taken a back seat to other priorities, much of it is doable without great cost. Water utilities and municipalities, for example, could bolster their embrace of the power of data — “digital water” — to gain insight about when, where, and how much to invest in their systems. The opportunity to gather and integrate data using current data collection systems — combined with evolving next-generation, cost-effective sensors and smart devices — provides the input to allow for the predictive analytics to detect leaks, forecast usage, reduce costs, and everything in between.

Asked about their data’s meaningfulness, nearly 60 percent of respondents to Black & Veatch’s survey reported that, while they were collecting “lots” of data, it wasn’t being leveraged to actionable information. Just 20 percent said they were making the most of their data, with only 15 percent admitting they were corralling “some” data and using it effectively. Siloed data amounts to lost opportunity, costing operators the vast benefits of expansive data harvesting that can give meaningful insights about their entire water ecosystem.

Investment should be thoughtful, with utilities carefully assessing demand trends in making sure that such things as new pipelines or substations are slotted for the right places before any ground is broken on such projects.

Utilities also might consider upgrading their operational networking. Many may have lacked remote access (VPN) that would have allowed them to tap into their systems, crimping their ability to monitor assets or to collaborate. Such distance and disconnect between operations staff and their bosses can delay reaction time when it’s needed most.

Getting commercial insurance also may be an option for water utilities as a resilience hedge against future unforeseen disruptions and the absence of federal financial assistance.

The Time To Act Is Now

Across the industry, no matter the utility’s location, the trend is to become more proactive when it comes to building resilient water supplies — and to invest in a future need not yet entirely realized. Many of these efforts are regional.

And, while the added complication of COVID-19 has further strained the bottom lines of many water utilities, this moment presents the opportunity to accelerate innovation in strategy, operations, and funding to propel sustainable, resilient systems.

Only with time will the extent of COVID-19’s financial implications on the industry become clearer. But the current pandemic situation demonstrates firsthand the critical need for water utilities to continue to evaluate and plan for vulnerabilities and potential system failures to mitigate against a changing, uncertain future.

Whether it’s a global pandemic, catastrophic droughts, raging wildfires, or destructive floods, utilities must make their systems reliable and resilient to meet the challenges.

References:

1. https://www.bv.com/perspectives/2020-strategic-directions-water-report

2. https://www.epa.gov/waterresilience/americas-water-infrastructure-act-riskassessments-and-emergency-response-plans

About The Authors

Karen Burgi is a regional planning lead for Black & Veatch’s water business.

Jo Ann Jackson leads Black & Veatch’s national “One Water” planning practice.

Kevin Laptos is the national distribution and collection system planning practice leader for Black & Veatch’s water business.

Ed Rectenwald is a hydrogeology national practice lead for Black & Veatch’s water business.

Jim Schlaman is the director of planning and water resources for Black & Veatch’s water business and serves on the One Water Council for the U.S. Water Alliance.