How Water Suppliers Can Improve Resilience Throughout Hurricane Season

By Michael Griffiths

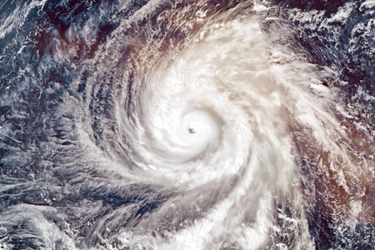

Exactly 16 years after Hurricane Katrina devastated the city of New Orleans on its way toward becoming the most expensive natural disaster in U.S. history,1 Hurricane Ida slammed into the Gulf Coast with great force.2 The storm would eventually move north, leaving a trail of destruction across much of the Eastern Seaboard. Nearly a month later, many who were in its path are still feeling the effects.

Picking Up The Pieces

The heavy rains and violent winds took lives, caused billions of dollars’ worth of property damage, and disrupted power grids, communication lines, supply chains, and transportation routes.3 The storm also wreaked havoc on water systems, particularly in eastern Louisiana, where residents were encouraged to boil water before drinking4 and to refrain from running washing machines and dishwashers5 to ease the strain on sewer systems.

The efforts to repair these systems could take months, but the relief might be short-lived. Hurricane season doesn’t end until Nov. 30, and historically, most storms don’t occur until after Aug. 1.6 Moreover, recent studies have revealed that hurricanes are growing stronger as climate change intensifies.7 2021 has been another year of “above-average” activity.

To prevent increasingly disastrous disruptions to America’s water supply, businesses and municipalities must find a way to fortify already fragile water systems.

Feeling The Strain

A hurricane can impact the water supply in multitudes of ways. The physical damage caused by fallen trees and other debris can puncture pipes and contaminate drinking water, exposing communities to diseases such as cholera, hepatitis, and E. coli.9

Extensive flooding can also create health hazards as sewers overflow10 and contaminate clean water sources. In these situations, municipalities might be forced to issue boil orders, as was the case in parts of Louisiana after Ida.

Flooding and high winds can also damage the electrical equipment essential to generating power and managing the flow of water to power plants, dams, and fuel refineries, causing significant disruptions to energy production. Without electricity and fuel, water systems can’t function. And without water systems, people will not have clean water for their homes or businesses.

Although such scenarios are often thought of as unlikely or “worst-case,” they’re becoming increasingly real. As mentioned before, this year’s storms have exposed vulnerabilities in the water supplies of communities throughout the Southeast, especially in rural areas, and the damage is often widespread.

As Ida has tragically demonstrated, those least prepared for disaster are often hit the hardest. With the peak of 2021’s hurricane season upon us, leaders managing the nation’s water systems must take the following steps to avoid further tragedy:

1. Develop a comprehensive emergency response plan.

The Environmental Protection Agency provides an emergency response plan (or ERP) template11 to help wastewater utilities plan for disasters, and it can serve as a useful starting point for documenting your own strategy.

An ERP should outline all the processes, resources, and protocols that you’ll rely on in the event of a crisis, and in as much detail as possible. Although all the information included in your plan is important, your success in implementing it will ultimately depend on two factors above all others: effective communication and clearly defined roles.

Regardless of how a hurricane impacts your water system, you’ll have to convey those impacts to a variety of external stakeholders to preserve trust and credibility, issue guidance, and enlist assistance. Your ERP should identify each of these stakeholders and include robust guidelines on how and when to engage them.

You’ll also have to preserve clear internal communications, which could easily be obstructed due to any number of reasons during a hurricane or other natural disaster. Fortunately, communication gets easier when everyone in your organization knows precisely what their role is when disaster strikes. Your ERP should identify an emergency response role for all personnel (at smaller facilities, workers might take on multiple roles), and designate an emergency response lead capable of both effective communication with external stakeholders and guiding internal remediation efforts.

2. Secure generators and alternate power.

During a disaster, keeping the pumps running may require backup sources of power. To ensure water keeps flowing to customers, identify a backup generator that can power each well or plant in the event of a power outage. If a pump sustains physical damage, there should be a contingent well capable of providing the necessary supply.

Particularly in rural areas, damaged electrical lines can shut off access to water wells for months at a time. To prevent this from happening, you need not only enough generators, but also enough fuel to power them for an extended period. Refineries are often disrupted in the wake of a hurricane, so don’t wait to obtain the fuel you’ll need in a crisis. Similarly, have a licensed mechanic inspect your generators annually (or more frequently during hurricane season) to ensure that they’re capable of providing sufficient power.

3. Develop relationships with utilities and other stakeholders.

You might have entire communities counting on you to continue operating after a hurricane hits, but you can’t and shouldn’t protect your systems alone. And depending on your location and the storm’s trajectory, you could incur severe infrastructure damage just like other facilities — a concern that is especially true for systems dependent on aging infrastructure.

With that in mind, coordinate with local emergency responders, neighboring utilities and power companies, and upstream facilities to establish clear lines of communication and a direct course of action in an emergency. Prioritize your hypothetical needs in the event of a disaster, and then identify external parties that could help you address each one. Once they’ve been identified, reach out to them to verify their willingness to help and to ensure they understand how and when to best deliver aid.

Do The Small Things Now

There are always mitigation steps you can take prior to a natural disaster to lessen its negative impact. Installing physical barriers around vital equipment; elevating electrical panels, pumps, and chemical tanks; cleaning up debris that could clog drains and outflow points; and similar activities will help you increase your operation’s resilience and speed up recovery. Although these activities might require an initial investment of time and labor, they’ll help you avoid much higher costs if (and when) the next major hurricane makes landfall.

References

- https://www.britannica.com/event/Hurricane-Katrina

- https://www.npr.org/2021/08/30/1032340262/hurricane-ida-strikes-the-gulf-coast-16-years-after-katrina

- https://www.newsy.com/stories/damage-from-hurricane-ida-estimated-to-cost-18-billion/

- https://www.circleofblue.org/2021/world/hurricane-ida-damages-louisiana-water-systems-cuts-water-service/

- https://www.gccapitalideas.com/2021/09/02/post-event-report-hurricane-ida-gulf-coast-landfall/

- https://www.wtsp.com/article/weather/tropics/peak-hurricane-season-begins-in-mid-august/67-fdb3166b-7f6e-4886-a8b0-64eb0a9fc7c4

- https://www.pnas.org/content/117/22/11975

- https://disasterphilanthropy.org/disaster/2021-atlantic-hurricane-season/

- https://connectforwater.org/how-do-hurricanes-affect-water-quality/

- https://www.smartcitiesdive.com/news/there-may-be-sewage-in-your-citys-drinking-water/575925/

- https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2021-08/ww-erp-template-instructions.pdf

Michael Griffiths is the vice president of the Water and Community Facilities division at CoBank, a national cooperative bank serving vital industries across rural America by providing loans, leases, export financing, and other financial services in all 50 states. He holds a bachelor’s in management and a Master of Business Administration in finance from Northern Illinois University