Calling Out The EPA On Water Issues

By Kevin Westerling,

@KevinOnWater

Everyone must answer to someone — even the rule-makers themselves. While it may seem to water and wastewater utilities that the U.S. EPA is the end of the line, there is yet another government agency that holds the EPA's feet to the fire. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) is the nonpartisan auditing arm of Congress which investigates and evaluates the federal government, offering recommendations for improvement where shortcomings are identified. These recommendations may or may not be followed, but it is certainly a red flag when they go unaddressed, as if confirming disregard for the issue(s). And since part of the EPA's mission is to assist utilities in shared goals — safe water and environmental protection — EPA failures can have repercussions at the local plant level (that old saying about a certain waste product rolling downhill).

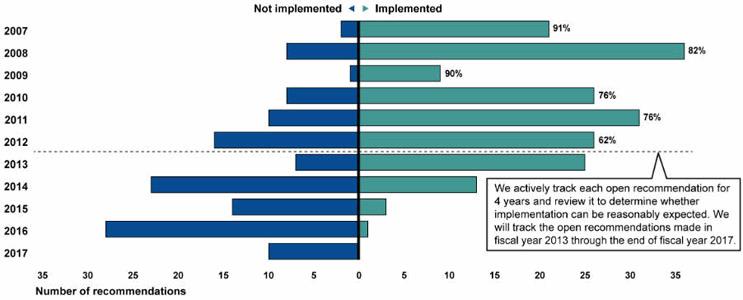

In September 2017, GAO published a status report on its recommendations to the EPA over the past decade, dating back to fiscal year 2007. The report covers the broad reach of EPA, beyond just water, but nearly 60 percent (189 of 318) of all recommendations fell into two categories that are important to water industry professionals — ‘Management & Operations’ (122 recommendations) and ‘Water Issues’ (67 recommendations), which includes infrastructure, drinking water, water quality, and ecosystem restoration. As of August 23, 2017, the EPA had failed to implement 52 percent of GAO’s recommendations for Management & Operations and 40 percent of those for Water Issues.

Source: GAO | GAO-17-801T

Notwithstanding the GAO report, which spans several presidential administrations (but mostly, and the entirety of, the Obama era), it should be noted that EPA governance is changing under President Trump. How these changes will affect EPA priorities going forward remains a question. What should be certain is that GAO will continue to point out EPA weaknesses, and that utilities will have to perform to standards with or without the proposed improvements. The hope, however, is that the EPA will pay heed to the following unaddressed concerns.

Management & Operations

Management of grants: According to GAO, when it comes to distributing money for repairing aging water infrastructure, preventing pollution, etc., the EPA “did not have the information it needed to allocate grants management resources in an effective and efficient manner.”

To manage a huge portfolio — $3.9 billion in 2015, for example (~49 percent of total budget) — the EPA relies on grant specialists and project officers; and yet, the report noted, “EPA had not identified project officer critical skills and competencies or monitored its recruitment and retention efforts for grant specialists.” For such an important job, handling nearly half of EPA’s budget, GAO suggests that the agency create mechanisms to ensure that the proper personnel are in place.

“We recommended that EPA, among other things, develop documented processes that could be consistently applied by EPA offices to collect and analyze data about grants management workloads and use these data to inform staff allocation. We also recommended that EPA review project officer critical skills and competencies and determine training needs to address gaps and develop recruitment and retention performance measures and collect performance data for these measures.”

Information security: The EPA, like many federal agencies, relies on private companies to operate computer systems and process information. Naturally, these companies must also provide cybersecurity, but resiliency should be assured by the EPA rather than entrusted to the contractor and taken for granted. The initial recommendations on oversight, stated below, were issued back in August 2014, yet the GAO couldn’t verify implementation in 2017, despite the fact that vulnerable computer systems (email servers, for instance) and large-scale hacks have been a subject of national concern.

“We recommended that EPA develop, document, and implement oversight procedures for ensuring that, for each contractor-operated system: (1) a system test is fully executed and (2) plans of action and milestones with estimated completion dates and resources assigned for resolution are maintained.”

Workforce planning: Here, treatment plant workers may actually be able to empathize with the plight of the EPA. GAO has concerns about “whether [EPA] can sustain a workforce that possesses the necessary education, knowledge, skills, and other competencies” to be successful, indicating that its workforce plan doesn’t programmatically integrate with its overall plan and budget formulation.

“Without alignment to the strategic plan, we concluded that EPA was at risk of not having the appropriately skilled workforce it needs to effectively achieve its mission. We recommended, among other things, that EPA incorporate into its workforce plan clear and explicit links between the workforce plan and the strategic plan, and describe how the workforce plan will help the agency achieve its strategic goals.”

(Note to young talent in training: The environmental industry needs you!)

Water Issues

A recurring theme with a number of Management & Operations recommendations, “oversight” reemerged in GAO’s evaluation of the EPA on Water Issues. This recommendation was hard to miss the first time around, issued in a May 2012 report entitled Nonpoint Source Water Pollution: Greater Oversight and Additional Data Needed for Key EPA Water Program, essentially dealing with section 319 of the Clean Water Act. And while oversight was the top-line critique — i.e., lack of verification that the grants provided under section 319, designed to curb nonpoint source pollution, were being implemented correctly or effectively — it also suggested that the end goals were in fact not being met.

“We found that EPA’s regional offices had varied widely in the extent of their oversight and the amount of influence they had exerted over states’ nonpoint source pollution management programs. In addition, EPA’s primary measures of effectiveness of states’ management programs did not always demonstrate the achievement of program goals,” the report disclosed.

To remedy this problem, GAO proposed a two-part fix:

“[W]e recommended that EPA (1) provide guidance to its regional offices on overseeing state programs and, (2) in its revised reporting guidelines to states, emphasize measures that more accurately reflect the overall health of targeted water bodies and demonstrate states’ focus on protecting high-quality water bodies, where appropriate.”

Pursuant to the recommendation, the EPA did issue guidelines and a memorandum to regional officers which laid out expectations for section 319 oversight, but GAO followed up with a 2016 report stating that the EPA didn’t “completely address” the issue, lacking “specific instructions on how to review states’ plans and criteria for ensuring funded projects reflect characteristics of effective implementation and tangible results.” As for the second aspect of GAO’s recommendation, the EPA fell even shorter; the report related that “according to EPA officials, the agency planned to make changes to some of the program’s measures of effectiveness.” Merely planned, not implemented.

Sometimes “best-laid plans” go awry, which is a fate that can be forgiven. Less forgivable is having no plan for improvement, especially if deficiencies are recognized and solutions are spoon-fed. For all of the EPA’s great people and achievements over the past half-century, if the agency fails to uphold its mission to protect human health and the environment, we all pay the price.