Biosolids In The Urban Metropolis: Long-Term Planning For New York City

By Jennifer McDonnell And Pam Elardo

Everything may be bigger in Texas, but there is more of everything in New York City — including biosolids, which require smart, sustainable management.

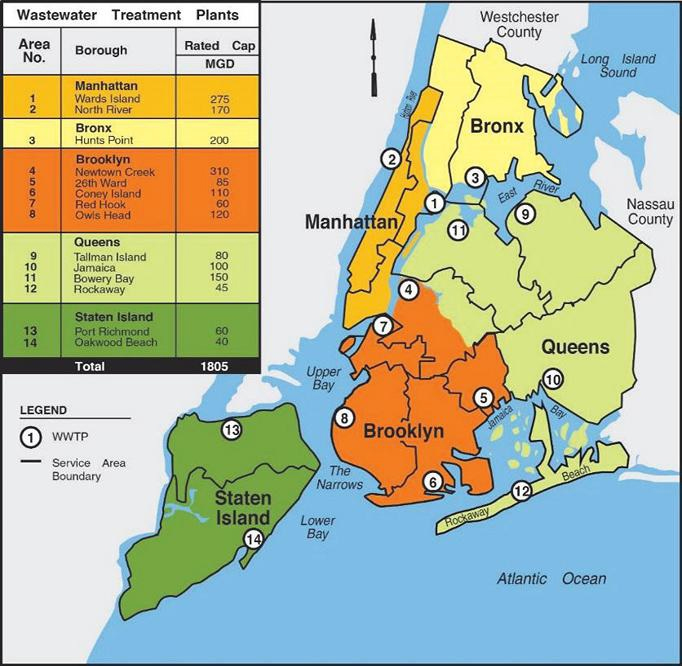

New York City is a bustling metropolis with over 8.5 million residents and millions more commuters and tourists. The Department of Environmental Protection provides clean drinking water as well as stormwater management and wastewater treatment to the city, across all five boroughs. Wastewater treatment is accomplished through a network of over 7,000 miles of local conveyance, 152 miles of intercepting sewers, 96 pump stations, four combined sanitary and storm flow retention facilities, and 14 wastewater treatment plants (range: 40 MGD to 310 MGD; 1.8 BGD total dry flow).

The waters surrounding the city are the cleanest they have been in over a century, thanks to the hard work of the department and specifically the team in the Bureau of Wastewater Treatment (BWT), which is about 1,800 people strong. As the bureau looks to the future, we are embracing a renewed focus on the wastewater treatment plants as resource recovery facilities — in fact the industry has been moving to rebranding WWTPs as WRRFs. When viewing these facilities as integral parts of sustainable communities, we see that the wastewater treatment plants not only provide the service of cleaning water, but they are also poised to extract energy and resources from the incoming stream of combined storm and wastewater. Given the size of our system and the significant infrastructure involved, realizing this transformation begins with a commitment to a mission and vision, and then detailed planning to incorporate innovation, technologies, and management strategies to achieve those goals.

Solid(s) Operation

The city produces an average of 1,400 wet tons per day of biosolids at six centralized dewatering facilities. The eight wastewater treatment plants that do not have dewatering equipment transport their liquid sludge either by barge or force main to the centralized facilities. The dewatering locations are serviced by multiple biosolids management vendors who use a combination of tractor trailers and long-haul rail to move the solids to a variety of end-use outlets. Currently, a majority of the city’s biosolids is directed to landfills for disposal; part of our vision and plan, driven by the mayoral goals outlined in OneNYC as “zero organic waste to landfill by 2030,” is to direct all that material to beneficial use. To achieve that, we have embarked on a master planning process to survey innovative biosolids processing technologies, market trends, and public policy rules.

As an agency committed to clean water, it is important to connect the dots on the solids fraction of this resource stream. We believe energy and biosolids are linked in resource recovery — with anaerobic digesters at all 14 of our wastewater treatment plants, we are investing in capital equipment to improve our solids processing trains through screening, thickening, digestion, heat recovery, and biogas upgrades to make and use more biogas. These investments will help us achieve other goals, which include energy neutrality at all of our treatment plants, and increase the quality of our biosolids. When managing the implementation of this vision across such a complex and distributed network, we must also take into account the unique aspects of each facility. They range in size, process flow, and equipment — and each faces its own challenges from equipment condition to staffing to regulatory mandates to community involvement.

BWT Vision: Achieve state of good repair through engaged employees and responsible asset management, and become a leader in wastewater resource recovery

New York City’s wastewater treatment plants

Recovering P

Outside the walls of our facilities, we are focused on understanding the nutrient cycles in our regional ecosystem, and what products are in demand that we can recover from our incoming resources. Nutrients have increasingly become a concern. Phosphorus recovery is an example of a relatively new innovation in the field that we are considering. Phosphorus (P) is an issue for our treatment plants when it precipitates as struvite and accumulates in our pipes and equipment, while nitrogen (N) loading and its effect on dissolved oxygen levels has been noted as a problem in some of New York City’s surrounding receiving waters. We are engineering ways to direct these nutrients either into the solids stream (P) or to the atmosphere (for N, in the form of N2). As we look to return biosolids to land as a soil amendment in our push to zero landfill, we must recognize that crop needs for P are generally lower than N. Coupled with the fact that our regional soils are not often P-deficient, if the concentrations of P in the solids increases while N does not, P in biosolids can outweigh the N crop needs at land application sites and create a limitation for agricultural use. There are already some regional farm fields that have historically received biosolids that are P-saturated and no longer able to utilize biosolids as a fertilizer because of that. Innovative technologies and chemical addition can allow for the extraction of P from the solids stream separate from the biosolids, and is something worth evaluating. This recovered P is having success in specialized fertilizer markets — as an ingredient in custom blends or relocated to geographies where P is in demand. This potential resource recovery opportunity from an end-use perspective must then be woven into our cost-benefit analysis for capital allocation, and the plant operations perspective.

BWT Mission: We safely convey and treat wastewater, manage stormwater, and recover sustainable resources to protect public health and enhance the environment to sustain the economy and the quality of life for all who live, work, and play in New York City.

Phosphorus recovery opportunity is just one example. Through our global peer network, we are also in the early stages of exploring metals, cellulose, and micronutrient recovery. We are also examining what potential biosolids-based products would be most valuable in the urban environment. Opportunities in this realm include manufactured topsoil, green infrastructure blends, or soil amendments for parks and green spaces. Also under investigation is the recovery of grit for use as a recovered sand or fine mineral base. New York is still very much a gritty city.

Solving For Sustainability

Underlying much of our approach are the previously referenced city goals, which are grounded in an awareness of our changing climate and the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. An integrated view incorporates the greenhouse gas impacts of our choices and evaluates those alongside the financial, operational, and other environmental considerations, and finally layers on the social impacts for a full “sustainability view” of our options. The social/environmental aspects often intersect. Resiliency planning is front and center in our city surrounded by water. With increasing extreme weather, we are concurrently protecting our current infrastructure from predicted storm surge elevations in the future, and all of our new construction incorporates resiliency as part of our sustainability review.

Ultimately, we see our potential to be a neighborhood provider of clean power, raw materials (metals, cellulose, fertilizers), and clean water to each and every neighboring community to our facilities. By investing in the long term through our commitment to comprehensive planning, we are mapping our plan of how we will achieve that vision. We know it will require a diversity of solutions, much like the diversity of our great city and our unique individual treatment plants. We know it will require significant capital investment and the tech-literate workforce of the future. We know it will require support from policymakers, community leaders, and our users, who are also ratepayers. Finally, we know it will require leadership and fresh thinking on how we operate, problem-solve, and work together.

About The Authors

Jennifer McDonnell is a resource recovery professional with 15 years in the fields of solid waste, recycling, and biosolids management. Currently the biosolids program manager for the City of New York, she is part of the Bureau of Wastewater Treatment at the Department of Environmental Protection, leading a renewed effort to increase the beneficial use of biosolids, realize GHG reductions, and transform treatment to resource recovery. Jennifer has a dual BA from Brown University in human biology and organizational behavior, is a certified recycling professional (Rutgers University), and a 2014 graduate of the Water Environment Federation’s Water Leadership Institute.

Jennifer McDonnell is a resource recovery professional with 15 years in the fields of solid waste, recycling, and biosolids management. Currently the biosolids program manager for the City of New York, she is part of the Bureau of Wastewater Treatment at the Department of Environmental Protection, leading a renewed effort to increase the beneficial use of biosolids, realize GHG reductions, and transform treatment to resource recovery. Jennifer has a dual BA from Brown University in human biology and organizational behavior, is a certified recycling professional (Rutgers University), and a 2014 graduate of the Water Environment Federation’s Water Leadership Institute.

Pam Elardo is the deputy commissioner for the NYC Department of Environmental Protection’s Bureau of Wastewater Treatment, which treats 1.3 billion gallons of wastewater annually. Prior to NYC, Pam directed the King County Wastewater Treatment Division, one of the largest public wastewater utilities on the U.S. West Coast. She also implemented the Clean Water Act with the Washington State Department of Ecology. Pam holds a master’s in environmental engineering from the University of Washington and a bachelor’s in chemical engineering from Northwestern University. She is a licensed professional engineer and certified WWTP operator.

Pam Elardo is the deputy commissioner for the NYC Department of Environmental Protection’s Bureau of Wastewater Treatment, which treats 1.3 billion gallons of wastewater annually. Prior to NYC, Pam directed the King County Wastewater Treatment Division, one of the largest public wastewater utilities on the U.S. West Coast. She also implemented the Clean Water Act with the Washington State Department of Ecology. Pam holds a master’s in environmental engineering from the University of Washington and a bachelor’s in chemical engineering from Northwestern University. She is a licensed professional engineer and certified WWTP operator.