As Climate Change Worries Deepen, Water Utilities Must Address Vulnerabilities, Raise Resilience

By Ed Rectenwald, Jim Schlaman, and Andrew Smith

The existential and operational threats posed by climate change are clear and imminent, if not present, but how ready — and how concerned — are water and wastewater utilities?

From chronic headaches about aging infrastructure to cyber threats and shifting regulations, water utilities have no shortage of complexities that keep operators up at night. Rising worries about climate change and its effects on the resilience of water systems increasingly are complicating matters, with a devastating Texas winter storm serving as the latest alarm in an industry that long has given the topic a relatively cold shoulder.

In February 2021, the powerful wintery blitz that blanketed much of the Lone Star State with snow, ice, and record low temperatures knocked out power and heat to millions of homes and businesses for days, disrupting crucial water service in the process. Many pointed to climate change as the likely culprit.

Dramatically, the Texas freeze underscored the often overlooked yet glaring interrelationship of energy, electricity, water, transportation, and communications infrastructure systems. When one fails, catastrophes can cascade.

That reality begs two questions as climate change — the force behind evidence of more severe and frequent storms — drives difficult decisions. Are utilities and communities doing enough to “harden” their water, wastewater, and stormwater infrastructures and assets against climate change, the phenomena manifesting itself elsewhere in seemingly more common droughts, flooding, hurricanes, and wildfires? Or are they at the very least starting to plan for such upgrades — and creatively sorting out how to pay for them — in the interest of dependable water security and supply? And in the scheme of things, how much hardening is enough?

The short answer: Water utilities could or should do more, as a survey of more than 200 U.S. water industry stakeholders for Black & Veatch’s recently released 2021 Strategic Directions: Water Report makes vividly clear.

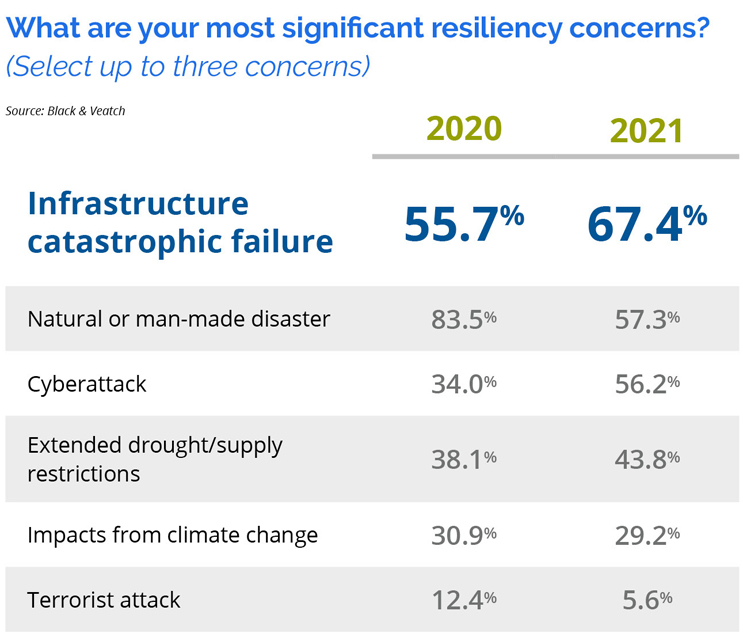

Even as water utilities serve as the glue that helps bind communities, climate change impacts ranked fifth among respondents’ most significant perceived resilience concerns, handily outdistanced by the top and perhaps predictable choice of two-thirds of the survey takers — potential catastrophic infrastructure failure in a sector that’s grappled for decades with aging infrastructure. Natural or human-made disasters — some associated with climate change — ranked second, cited by nearly six in 10 respondents (57 percent) — down dramatically from 84 percent in 2020. Extended drought and water supply restrictions followed at 44 percent, with climate change impacts finally coming in at 29 percent, relatively unchanged from the previous year.

While climate change and the challenging reality that it’s a moving target appears to get short shrift in decisions involving resiliency, increasingly extreme weather events still should compel water utilities — many underfunded and starved for capital — to proactively plan ways to harden their assets as a backstop against natural or manmade disasters. In 2020 alone, a historically busy Atlantic hurricane season produced 30 named storms, including a half dozen major hurricanes. Severe wildfires scorched millions of California, Colorado, and Oregon acres — and large swaths elsewhere around the globe — while flooding inundated portions of several states. This year, drought and wildfires continued to grip much of the western U.S.

Against that worrisome backdrop, federal help is on its way to hasten greater climate resiliency. Signed into law by President Biden in November, the $1.2-trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act includes $550 billion in new spending, including billions to modernize U.S. water, wastewater, and stormwater systems. Classified by the White House as “the largest investment in the resilience of physical and natural systems in American history,” the measure allocates nearly $51 billion to drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater infrastructure, along the way investing in water recycling for western U.S. states.

“Investing in infrastructure — specifically water — has vast support from the overwhelming majority of Americans. Water is too essential to wait,” Mami Hara, CEO of the US Water Alliance trade group, said after final congressional approval of the infrastructure bill, sending that 2,702-page measure to Biden for his ultimate signature.

“With enactment of the bipartisan infrastructure investment package, Congress and the (Biden) administration recognize the essential role water recycling is playing in helping communities confront the impacts of climate change and build more resilient and sustainable water resources for their communities,” added Patricia Sinicropi, the WateReuse Association’s executive director. “This is an important day for water in the U.S.”

Resiliency Still A Lesser Priority

Perhaps of little surprise, many system managers remain acutely focused on meeting state and federal water quality standards and simply keeping the system running. Addressing anything beyond the job’s operational mandates often tends to be deferred as “tomorrow’s crisis” — something to tackle only after today’s crises are dispatched.

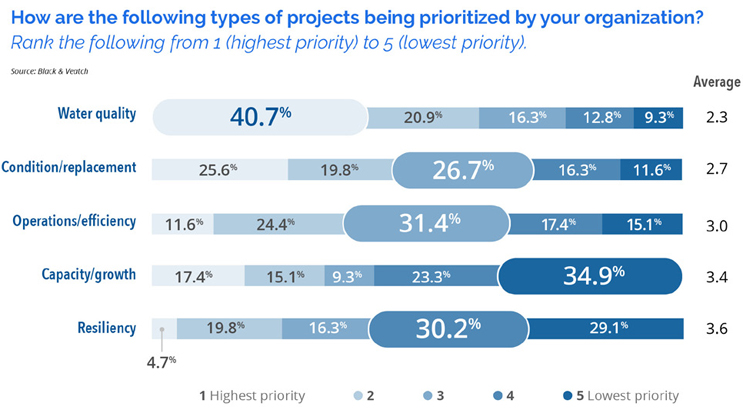

The Black & Veatch survey amplifies that. Projects that ensure or enhance water quality — the chief mandate of water providers — held the most sway among respondents, with roughly four in 10 casting that as their highest priority. Bolstering the conditions of assets or replacing them altogether was the chief priority of one quarter of respondents, followed by addressing capacity and growth (17 percent) and operations and efficiency (12 percent). Projects intended to improve resiliency drew just 5 percent, with nearly three in 10 labeling resilience as their lowest priority.

Larger water utilities — those serving at least 500,000 people — listed resiliency as their third-highest priority, behind water quality and matters involving asset condition or replacement. For utilities with fewer than 500,000 customers, resilience languished at the bottom of five priority choices, reflecting that resilience planning is a luxury for those smaller water systems.

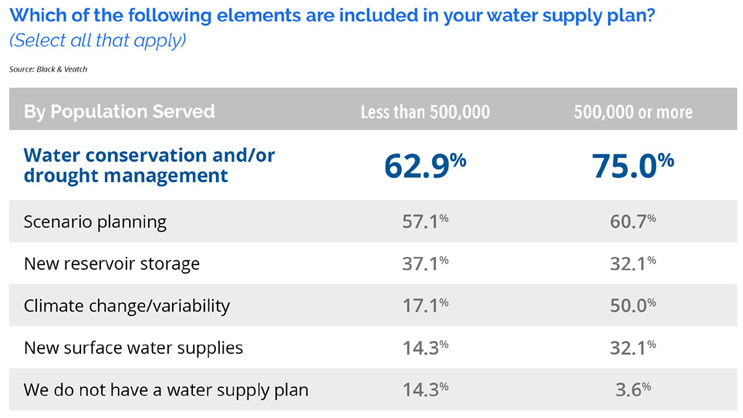

A similar split between larger and smaller water utilities surfaced when respondents were asked about elements of their water plan. Three-quarters of larger systems surveyed said water conservation and/or drought management was part of their blueprint, compared to 63 percent of smaller systems. Officials at systems of various sizes had roughly the same responses about scenario planning and new reservoir storage.

But a large gap emerged when it came to climate change or variability, with half the respondents at larger utilities saying such factors were part of their water roadmap — compared to 17 percent of smaller water systems.

Water’s Value And The Climate Threat

The U.S. built a lot of water and wastewater infrastructure more than a century ago, but capital spending has dropped off sharply. Until systems break, water and wastewater functions remain an “out of sight, out of mind” proposition. But breakdowns are happening more frequently, given the prevalence of aging infrastructure stressed by population growth and migration.

As climate change worries escalate — and citizens, regulators, and other stakeholders demand greater resiliency in such critical infrastructure — utilities large and small would be well-served to strategize thoughtfully now about upgrades, knowing that such projects are years in the making.

Water and wastewater utilities should begin by having earnest conversations with their boards, critical stakeholders, and customers about water’s value, pressing the salient point that the environment isn’t static.

Key to it all is understanding that it’s not about the infrastructure’s performance over past decades but what challenges the assets will have to handle sooner or later. And the fact that it’s far cheaper to repair or replace assets now before systems weaken and fail than playing catch-up — and pointing fingers — when trouble strikes .

.

About The Authors

Ed Rectenwald is a hydrogeology national practice lead for Black & Veatch’s water business.

Jim Schlaman is the director of planning and water resources for Black & Veatch’s water business and serves on the One Water Council for the US Water Alliance.

Jim Schlaman is the director of planning and water resources for Black & Veatch’s water business and serves on the One Water Council for the US Water Alliance.

Andrew Smith is the national watershed, stormwater, and flood management practice lead for Black & Veatch’s water business in the Americas.

Andrew Smith is the national watershed, stormwater, and flood management practice lead for Black & Veatch’s water business in the Americas.