A Comprehensive Approach: Flood Protection And Improved Water Quality For Denver Communities

By Ryan Crum

When confronted with resiliency issues, Denver took a multifaceted approach that showcases the city’s vision along with its technical know-how.

The City and County of Denver has experienced consistent population growth for decades, regularly outpacing the national average. As the city expanded over the last 100 years, homes, businesses, and streets grew into and encroached upon waterways, channels, and natural streams. Along with this encroachment came consistent flooding that resulted in damage to homes, roads, and businesses within the Montclair Basin, Denver’s largest basin. Despite the basin’s size, it lacked a defined waterway to the river and created a highly underserved area from a stormwater perspective, as well as a high risk for flooding for several hundred properties.

In 2015, the City and County of Denver developed a plan for addressing the existing storm water infrastructure , which quickly reached capacity during moderate to large storms. During the planning process, the city team recognized an opportunity not only to address flood protection but also improve stormwater quality, incorporate green infrastructure, and enhance public spaces in Denver’s neighborhoods.

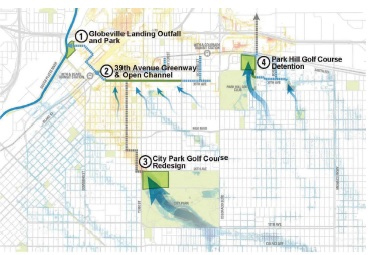

The solution is known as “Platte to Park Hill: Stormwater Systems,” a complex program made up of four separate but connected projects. The program creates new detention areas at two local golf courses, City Park Golf Course and Park Hill Golf Course, a linear greenway and open channel along 39th Avenue, and an enlarged outfall in Globeville Landing Park that feeds into the Platte River — the final stop for water flows in the drainage basin. Though these projects could have been completed separately to solve drainage issues, a combined effort creates a more capable system that also serves as an amenity for the surrounding neighborhoods. Therefore, the four projects were implemented via three separate alternative delivery method contracts to help with individual project timing and scoping.

With each of the four projects taking place within neighborhoods, a robust community outreach process was put in place to educate the community on the benefits, gain input on certain aspects of project design, provide construction updates, and more. Through the planning period, the city met with and sought feedback from more than 1,700 community members via 250-plus meetings, including numerous stakeholder working groups and large public meetings.

Stormwater Detention At A Historic Golf Course

One of the first and most important components of stormwater infrastructure is a carefully placed detention basin. Detention basins hold and slowly release large amounts of water during storms and are most effective when strategically placed in the middle of a basin. At the center of the Montclair Basin lies a 130-acre golf course, City Park Golf Course, which is surrounded by established residential neighborhoods. Golf courses are common hosts for detention basins because the feature can be easily integrated into the course and adds to its playability by creating water hazards.

Platte to Park Hill: Stormwater Systems is a complex program made up of four separate but connected projects that, once complete, will provide critical flood protection, increase neighborhood connectivity and public spaces, and improve water quality and existing infrastructure for current and future community members in north Denver. (Source: Design Workshop, Inc.)

To further enhance the stormwater system, the City opened up or “daylighted” existing storm channels and drainageways at the golf course that were buried under 150 years of urban development. By the time all channels were revealed through the daylighting process, the new reengineered streams ultimately created over a mile and a half of naturalistic riparian corridors across three of the projects. Additionally, the start of a water quality treatment train that runs through the projects begins at the golf course. A new regional trash vault and the stream’s wetland channel form its first components.

Community feedback was a major driver during each stage of the golf course’s design and construction. Local working groups were created and met throughout the life of the project to ensure that the course redesign matched community needs and desires. This process resulted in two primary concerns: trees and views. Working with the city forester and the community, the project team went to great lengths to prioritize the two. As a result, new routing and grading options were developed to maximize tree preservation.

Concerns over the impacts to views from surrounding neighbors also drove the team not only to identify and catalog priority views but also to develop full-scale 3D models and visualization graphics for each of the grading proposals to demonstrate the impact on views. The height of the new clubhouse was limited to preserve views for the adjacent neighbors. Other community-driven aspects included a full-size, 300-yard driving range, new sidewalks, a park-like space throughout the course, a healthy reforestation plan in line with the City’s forestry guidelines, and the incorporation of sustainable design and construction throughout the project site.

An Urban Greenway And Open Channel

Lower in the basin, where stormwater concentrates, the City selected an east-west corridor extending from 39th Avenue for a greenway and open channel. The greenway safely intercepts and conveys floodwater through newly constructed tunnels under nearby railroads and into an outfall before reaching the South Platte River. Greenways and open channels are popular solutions for water conveyance because of the wide space between river banks and the flood system allows water to pass through with less constraint on the river.

Given that the two-mile-long project site was located within a tight urban corridor of businesses and residents, a robust community outreach process was established early on, enabling the City to uncover design aspects most important to the community. Aspects addressed in the final design plan included gathering and recreational spaces, revitalization of historical elements, incorporation of native landscapes and materials, and increased connectivity for pedestrians, drivers, and bikers.

Additionally, when reconstructing the urban landscape, where possible, the city integrated various water quality features aimed at slowing down and filtering water through vegetation to remove contaminants, all while controlling storm runoff and nourishing greenery to help residents endure the climate shift toward droughts and rising temperatures. Greenways help remove waterborne contaminants by exposing them to sunlight and controlling stormwater across wide channels and gentle banks. To further the treatment process, over 50 streetside stormwater quality planters were installed to collect and filter water through various layers of vegetation and soils. Additionally, two new trash vaults added 1,000 cubic feet of trash collection in the basin.

Giving flood resiliency a lift: Construction activity via the City and County of Denver.

The Final Stop: Globeville Landing Outfall

For the final stop of the stormwater system, the city converted an existing park into an outfall, a recognized best practice for stormwater drainage systems. The newly created Globeville Landing Outfall has a capacity of 3,750 cubic feet of water per second and slows water before it reaches the Platte River.

Additionally, the outfall will serve as a habitat for wildlife and ecosystem restoration while improving overall water quality. Forming one of the last components of the treatment train, the outfall also contains a UV vault that treats low-flow stormwater before discharging it into the South Platte River.

The city’s public outreach program guided planning and helped the project team understand how residents were currently using the park next to the outfall. Feedback from several public meetings, stakeholder interviews, and focus groups led to a park design featuring grassy areas for sports and recreation, multiple bike and pedestrian trails, children’s climbing/play equipment, outdoor seating and gathering areas for families, and access to the river.

Extending The System Via An Additional Detention Basin

To bring the project full circle, the city also made plans to add additional drainage benefits in the nearby Park Hill Basin via a new detention area at Park Hill Golf Course. A pipeline is currently under construction that aims to connect the existing Holly Pond detention basin, which is too small to accommodate runoff from storms, to the new detention system at Park Hill. Overflows from Holly Pond will be conveyed west approximately 1,300 feet through a large box culvert to the new Park Hill detention pond.

All components of the “Platte to Park Hill: Stormwater Systems” project are currently underway, with completion expected in 2020. The project is an example of innovation using new green infrastructure to improve water quality and protect against flooding, while adding numerous other benefits to Denver communities, including enhanced connectivity, safety, and 12 acres of new park and recreation space. The project was included in the city’s Green Infrastructure Implementation Strategy and is frequently referred to as a successful example for other cities and communities across the country.

About The Author

Ryan Crum, senior engineer, public works, City and County of Denver, has 11 years of experience in storm and sanitary design, review, and construction engineering in the Denver area. He currently reports to the infrastructure project management team of public works at the City and County of Denver. He is the project manager for the Globeville Landing Outfall project, which includes five phases and nearly $75 million worth of construction. Ryan also provides technical guidance on the rest of the “Platte to Park Hill: Stormwater Systems” program, including the 39th Ave Greenway and Park Hill projects. He earned a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering from Texas Tech University and obtained his professional engineering license in 2013.

Ryan Crum, senior engineer, public works, City and County of Denver, has 11 years of experience in storm and sanitary design, review, and construction engineering in the Denver area. He currently reports to the infrastructure project management team of public works at the City and County of Denver. He is the project manager for the Globeville Landing Outfall project, which includes five phases and nearly $75 million worth of construction. Ryan also provides technical guidance on the rest of the “Platte to Park Hill: Stormwater Systems” program, including the 39th Ave Greenway and Park Hill projects. He earned a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering from Texas Tech University and obtained his professional engineering license in 2013.