Preventing Algal Blooms With A "Pinch Of Sugar"

By U.S. EPA

Have you ever walked or driven by a lake covered with a thick scum that looks like pea soup? This could be caused by blue-green algae, a cyanobacteria (“cyan” means “blue-green”) that is frequently found in freshwater ponds and lakes. Cyanobacteria are often confused with green algae because both can produce dense mats that may smell bad and hamper activities like swimming and fishing. However, unlike most green algae, blue-green algae can produce cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms (cyanoHABs). The highly potent toxins they make, called cyanotoxins, can harm people, animals, aquatic ecosystems, the economy, drinking water supplies, property values, and recreational activities.

For over a century, copper-based algaecides have been a popular way to control and eradicate all kinds of algae. However, the copper can harm fish and other aquatic species. These algaecides can also cause the cyanobacteria algae cells to burst, creating even higher levels of cyanotoxins in the surrounding water.

EPA researchers wanted to look at alternative ways to inhibit the development of cyanoHABs. CyanoHABs occur because of excessive amounts of nitrogen and phosphorous compounds in water, which mainly come from fertilizers and other human activities. All microorganisms need nitrogen and phosphorous compounds to survive and grow. However, because cyanobacteria make their own food through photosynthesis, they can out-compete other microorganisms, like proteobacteria, for access to the nitrogen and phosphorous compounds. As a result, cyanobacteria numbers can increase rapidly, causing an algal bloom.

The most common fresh-water cyanobacterium in U.S. waters are Microcystis, which produce the toxin microcystin. Therefore, the study focused on how to reduce Microcystis numbers and microcystin toxin levels. EPA researchers wanted to find out if adding a food source (glucose) would allow other bacteria to better compete with the cyanobacteria and prevent or reduce the development of cyanoHABs.

It’s All In The Timing

The researchers collected weekly water samples from an Ohio lake during the 2021 bloom season. Early in the summer they measured low levels of both cyanobacteria and proteobacteria in the lake water. Later in June, the warning signs indicated a coming cyanoHAB and researchers were prompted to begin the experiment.

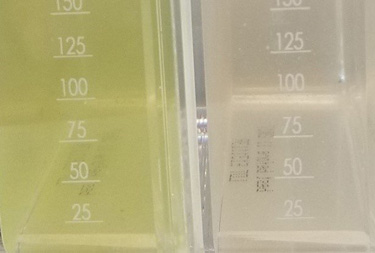

In the controlled environment of the laboratory, scientists filled two sets of flasks with lake water. Glucose was then added to some flasks while nothing was added to the control flasks. After two weeks of incubation, researchers measured the amount of microcystin toxin in each flask. The lake water treated with glucose had 80 to 90 percent less microcystin compared to the control flasks.

Researchers also quantified the number of Microcystis cells in the glucose treated and control flasks. Almost no Microcystis cells were detected in the glucose treated flasks, while the number of proteobacteria increased.

Next Steps

Although the glucose inhibited the cyanoHABs development in the laboratory, scientists would like to test this approach in lakes. There are other considerations as well. For example, although proteobacteria and other bacteria are less toxic than cyanobacteria, their growth may potentially produce other problems. As EPA scientist Dr. Steve Vesper notes, “The long-term solution to cyanoHABs is to reduce the quantity of nitrogen and phosphorous compounds entering rivers and lakes. The use of glucose is only a stop-gap measure on the way to finding a permanent solution to the problem of cyanoHABs.”

Learn More:

- Cyanobacterial Harmful Algal Blooms (CyanoHABs) in Water Bodies

- Article: Prophylactic Addition of Glucose Suppresses Cyanobacterial Abundance in Lake Water.

- Article: Use of qPCR and RT-qPCR for monitoring variations of microcystin producers and as an early warning system to predict toxin production in an Ohio inland lake.

- Article: Cyanotoxin-encoding genes as powerful predictors of cyanotoxin production during harmful cyanobacterial blooms in an inland freshwater lake: Evaluating a novel early-warning system.