Healthy Floodplains Reduce Nutrient Pollution

By Olivia Dorothy

Six key floodplain restoration designs can maximize nutrient removal in rivers.

This blog was written by Olivia Dorothy, Upper Mississippi River Basin Director, American Rivers & Brad Gordon, 2017-2019 American Rivers Lapham Fellow, currently the Southern Minnesota Program Manager at Great River Greening

In the Midwest, nitrogen and phosphorus pollution from farms is a persistent problem. In excess, these nutrients, which plants need to thrive, can cause toxic conditions in lakes, rivers, streams and aquifers. Too much nitrogen in a water supply can interrupt the delivery of oxygen to your body’s cells, which can lead to death, particularly in infants. Both phosphorus and nitrogen pollution can also contribute to toxic algae blooms in lakes, rivers and estuaries. The over-production of blue-green algae can suck all the oxygen out of the water column and cause massive fish kills. Some types of algae can also produce a toxin, microcystin, that can cause a range of stomach problems and liver failure.

In 2014, a large toxic algae bloom in Lake Erie caused 400,000 people in Toledo to lose access to clean drinking water.i Nutrient pollution-fueled “dead zones” along the U.S. coasts costs our seafood and tourism industries at least $82 million a year.ii Even communities along hundreds of miles of the Ohio River had to issue drinking water advisories in 2019 due to drought-like conditions that helped the toxic algae flourish.iii

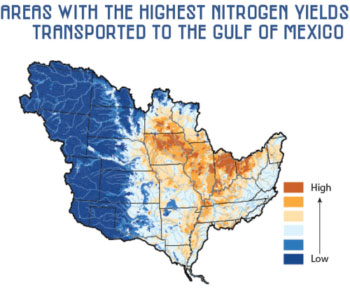

While nutrient pollution is a global problem, it is particularly prevalent in the Upper Midwest Corn Belt. Corn requires massive amounts of fertilizer that farmers deliver in the raw, inorganic forms. The inorganic forms of fertilizer are more water soluble, meaning the plant can take up the nutrients faster. But it also means that they are easily washed downstream during precipitation events, where they cause problems for aquatic ecosystems and drinking water supplies.

In addition to floodplain restoration’s potential to remove nutrient pollution from rivers, floodplain restoration has the benefit of providing many additional ecosystem services for communities. Reconnecting and restoring floodplains can help convey floodwater away from people and critical infrastructure, provide habitat for native plants and animals, recharge groundwater supplies, spur economic developing and property tax revenues, and increase the quality of life for communities by providing natural areas for recreation and relaxation.v

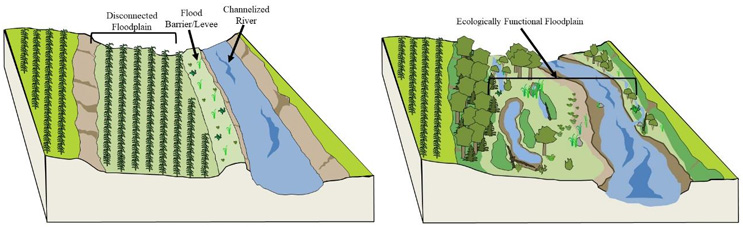

This is a depiction of a disconnected and non-functional versus an ecologically functional floodplain. Ecologically functional floodplains flood regularly without constructed barriers or incised main channels that prevent water from entering the floodplain during high-flow events. They are also capable of supporting plant and animal communities native to that region.

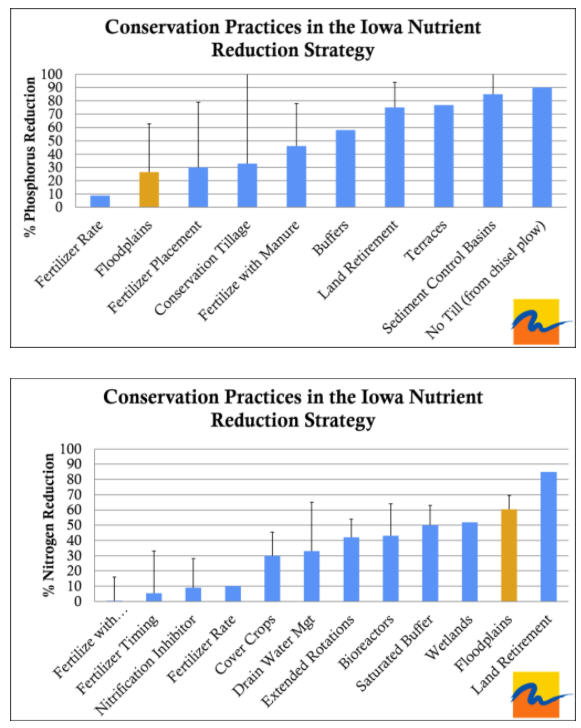

To better understand the nutrient removal potential of ecologically healthy floodplains, American Rivers conducted a literature review of over 200 studies from North America and Europe, 40 of which contained relevant data for our study. We found that floodplain reconnection and ecosystem restoration has the potential to permanently remove both nitrogen and phosphorus from the water column.

Based on literature reviewed, The mean removal of nitrate-N (NO3–-N), the primary form of N in floodplain studies, was 200 (SD = 198) kg-N ha-1 year-1, and of total or particulate P was 21.0 (SD = 31.4) kg-P ha-1 year-1.

The literature review also found that nutrient retention potential of floodplains is likely based on a few key design features. These include:

- Engineering the floodplain landscape to slow the water down. Although more flow across the floodplain could lead to a greater total mass of nutrients removed, the floodplain will lose effectiveness (the percent removal) as flow rates increase.

- Incorporating a permanently inundated wetland in the floodplain area. Permanent inundations with shallow or gently graded banks provide the most aquatic-terrestrial fringe habitat that is ideal for bacteria that remove nitrogen. Ephemeral wetlands that dry out completely and ponds with steep banks have limited nitrogen removal potential.

- Ensuring geomorphic diversity across the floodplain. Incorporating dips and swells into the floodplain landscape will help slow the water down so it can drop out phosphorus laden soil. Most soil is consolidated and buried on the floodplain and will not be released over the long-term.

- Restoring dense vegetation in the floodplain. Vegetation improves nutrient removal by providing organic matter for denitrifying microbes and slows water flow for better sedimentation and accretion.

- Harvesting vegetation from floodplains where feasible. This may aid in phosphorus removal, but caution should be taken due to the unknown impact on native plant communities.

- Restoring floodplains along waterways with higher concentrations of nutrients. Floodplains can permanently remove large amounts of nutrients as long as the water is slowed down to maximize nutrient removal.

Floodplain restoration should be used more in the Midwest as a tool to remove nutrient pollution. Too often, floodplain development projects overlook restoration as an option. Ecosystem restoration is often perceived as having a low or negative return on investment. Home buyouts in floodplains might allow the river to be reconnected, but the ecosystem functionality is not restored – the land is usually maintained as paved or turfed “open space.” Where ecosystem restoration projects do take place in floodplains, reconnection to the river is rare as funding sources usually prohibit restoration projects in frequently flooded lands.

Our publication adds to a growing body of evidence that floodplain restoration is an essential tool to improve water quality and build more resilient communities.