Financing Infrastructure Through Environmental Impact

By Julie King

With Environmental Impact Bonds, everyone can win. Shared risk means there are no big losers even if the project falls short.

Environmental finance was in the spotlight recently with two fixed income products. In September, DC Water and Sewer Authority (DC Water) issued the first Environmental Impact Bond (EIB) as part of its $2.6 billion program, DC Clean Rivers Project. The EIB will provide up-front capital for the construction of green infrastructure for the Rock Creek sewer shed with the aim of reducing the approximately 2 billion gallons of combined sewer overflows (CSO) that pollute local watersheds and tributaries each year when stormwater runoff exceeds the drainage capacity of the sewage system. The five-year, $25 million EIB was sold by private placement to two investors, Goldman Sachs Urban Investment Group and the nonprofit investment fund, Calvert Foundation.

In October, the City of Gothenburg, Sweden received the 2016 UNFCCC Momentum for Change Lighthouse Award as the first city in the world to issue a green bond. Proceeds from the green bonds are being used, within the city’s stringent environmental framework, to fund climate change and environmental sustainability projects that aggressively promote its objectives of transitioning to a low-carbon economy and climate-resilient growth.

These two investment instruments represent a growing trend — and opportunity — for infrastructure finance, particularly for water infrastructure. UN Water has concluded that “...water is the primary medium through which climate change impacts the earth’s ecosystem and people ... [and] adaptation to climate change is mainly about better water management.”i By combining the EIB’s mandate of investing-for-impact with increasing demand from investors for Environmental-Social-Governance (ESG) investments, it is no longer contradictory to talk about building infrastructure and protecting the environment.

Impact Bonds: Innovation In Financial Structure

The EIB issued by DC Water is a financing mechanism designed to share risks and align incentives between investors and the municipality. DC Water uses the EIB proceeds to pay for the costs of installing green infrastructure. Using a tiered payment approach to share performance risk, the amount of the return then paid to investors is tied directly to the degree of success or failure of the green infrastructure in achieving its impact objective: managing stormwater runoff.

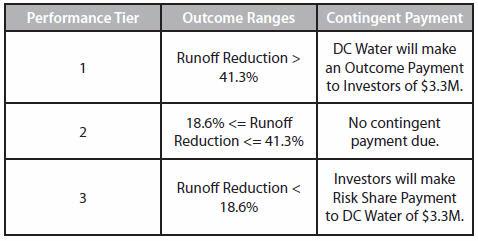

It will be considered successful if it falls within the conditions of Tier 2 of the payment structure (see Table 1). If the green infrastructure exceeds expectations, DC Water will make an Outcome Payment to investors for sharing the performance risk; if it falls short, investors will make a Risk Share Payment to DC Water. If the green infrastructure is successful in controlling stormwater runoff and managing the problem of CSOs, it will be validated as an effective climate adaptation tool, which is also a goal of the EIB.

“The Impact, from an investor perspective, is about improvement to the water system,” explains Derek Strocher, CFO of Calvert Foundation. “The return mechanism ... is tied to the outcome results. If the project outperforms, then investors receive an additional payment. If the project underperforms, then investors pay back a risk sharing amount.”

Strocher continues. “What we, as an investor, are doing is encouraging service providers like DC Water to take a chance on an impactful project like green infrastructure by offering to soften the blow if doesn’t work out .... Impact bonds can encourage all sorts of companies to take chances with their businesses to improve the environment ... or any other social issue they are qualified and confident to tackle by knowing that if they don’t get the (full) results they hoped for, there’s someone there to share some of the pain. If it does work out, then everybody wins, including/especially them by growing their business.”

Table 1: Tiered Payment Structure (Source: DC Water EIB Fact Sheet).

Impact Investing Sector

Impact Bonds are one of the innovative financing mechanisms within the impact-investing sector. ii The term “impact investing” was first coined at a convening of investors and philanthropists organized by the Rockefeller Foundation in 2007 to brainstorm how to entice private capital to fund programs and projects for the public good. Impact investing quickly evolved into a nascent global industry,iii and by 2010, it was officially recognized as a separate asset class by JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs, and other global financial institutions.iv

The objective of impact investing is simple: “unlock significant sums of private investment capital to complement public resources and philanthropy in addressing pressing global challenges.”v While sums are still small in comparison to total investments, in the 2016 Annual Impact Investors Survey from the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN), a reported $15.2 billion in impact investments was made in 2015, with respondents expecting to increase investments in 2016 by 16 percent, to $17.7 billion.vi

Impact Bonds were an impact-investing tool that gathered momentum initially in the U.K., ultimately resulting in the Social Impact Bond (SIB) to reduce recidivism at HMP Peterborough in 2010. Since then, more than 60 impact bonds have been launched worldwide, with the DC Water EIB being the latest example of innovation as the first-ever “2.0” version of an impact bond.

Impact Bonds 2.0

Based on the collective experience of impact bond veterans Goldman Sachs and Calvert Foundation, the DC Water EIB was designed as a model that other municipalities and companies can use to attract traditional fixed income investors, not only to fund reduction of CSOs but to encourage the use of impact bonds and to scale the use of proven environmental solutions to infrastructure needs.

Before coming to Calvert Foundation, Strocher was a member of the Working Group for Development Impact Bondsvii during his tenure at the World Bank. He is especially well positioned to contrast the EIB with early constructions of impact bonds.

“IBs 1.0 were investments in projects,” Strocher comments. “If the project failed for any reason (e.g., the service provider turned out to be inadequate, the potential results were overestimated, etc.), then the investor likely lost their money .... Investors in IBs 2.0 are fixed income investors that largely aren’t seeking significant risks (e.g., new intervention approaches, sovereign risk, risk of inexperienced service providers, etc.) in a project structure, all for a modest return.viii The 2.0 model offers those investors the support of a company’s underlying business, on top of which they share (to varying degrees by structure) the outcome risk. That risk profile can reach typical fixed income investors.”

Strocher explains the attraction of impact bond investments for a mission-oriented investment firm, such as Calvert Foundation and for fixed income and impact investors generally.

“We analyzed [DC Water] (for credit risk) and the outcome return as a separate risk analysis to determine whether the financial return potential [as risked] combined with the Impact potential would meet our Impact investing hurdles. The first risk analysis is very common for a fixed income investor, and returns are commensurate. The second risk analysis, which layers on a second level of return/or repayment, is where the innovation lives. The risk we are sharing is about the success or failure of green infrastructure to deliver its intended results. We can do that by funding the project through a company and not having to put our principal at the same risk as project financing. We still accept DC Water’s credit risk ... (or) other service providers in other deals. So, while this deal carries little principal risk for investors (and hence returns are commensurate), it carries substantial total return risk based on the success of the green infrastructure. In 1.0 models, there was a need for an intermediary to “manage” the performance of the service providers, but in a 2.0 model, the incentives are aligned much better because the service provider is highly motivated to manage performance because their company is underpinning the project and will benefit by producing successful outcomes, even though that means paying a higher (success) return on the IBs. This is the big difference between 1.0 and 2.0: the service provider (the one creating the Impact) has full skin in the game.”

Green Bonds: The City of Gothenburg, Sweden

In 1987, Gothenburg’s Board implemented a comprehensive environmental strategy to remediate the consequences of the city’s history of heavy industry and move toward a sustainable urban environment. As one of Sweden’s largest enterprises, the city established the environmental framework as the starting point and overarching standard for all its subsidiaries and projects.

Gothenburg, Sweden

Magnus Borelius is Head of Treasury at the City of Gothenburg and is responsible for the green bond (GB) program. Enjoying a triple-A municipal rating, the city has issued four green bonds since 2013 for a total of 4.36 billion Swedish Kronor (approximately $488.2 million), which represents 10 percent of the city’s outstanding debt. A new issue is planned for 2017. He explains their GB strategy.

“As part of Gothenburg’s framework of meeting climate change and sustainable environmental objectives, we established categories, such as waste management, sustainable transportation, water management, etc. Some of these are smaller projects. But there are larger projects, as well ... We have not defined what is ‘green’ or ‘not green.’ Instead, we established these categories, and investors in the green bonds know their money will be going to projects that fall within one or more of these categories.”

Borelius continues. “When we started, we didn’t know if this would succeed or if there would be demand from investors. We were surprised by the huge interest from investors. All of our green bonds have been oversubscribed ... [and] we have investors calling for private placement of the future green bonds we issue. They are mostly institutional investors — bank treasuries, asset managers, pension funds, insurance companies ... [that] are Swedish, Scandinavian, and from Europe, especially Norway, Germany, [and] Switzerland.”

Shared Features

Common to both bonds is achieving an environmental impact and doing so through rigorous vetting processes. Gothenburg started by having the GB investment structure validated by an independent evaluator.ix Thereafter, all investment targets were jointly vetted and selected by the City Office, made up of the departments of Urban Development and Treasury. The Environmental Administration scrutinizes their selection, with final approval for funding verified by the City Executive Board.

Similarly, the EIB was designed with outside counsel and independent advisors. The parameters in the tiered performance structure were established by DC Water from existing runoff measurements and verified by outside engineers, with final approval by the investors.

The approach to measuring results varies between the two bonds. Where Gothenburg has no formal evaluation standard, the EIB ties returns to verified results. But both structures require monitoring and reporting on compliance with the environmental objectives. For the GB, each subsidiary reports regularly on project status and Treasury monitors every project’s economic development, including environmental indicators. In turn, this information is included in annual reports to investors.x

Distinct Differences

Gothenburg purposely chose not to issue “impact bonds” because of how “impact” might suggest a political agenda. Instead, issuing “green” bonds aligned with a more traditional financing structure and a universally held standard in Sweden of benefitting the environment. This crossed party lines and was a common denominator for small and large companies in the city’s portfolio. This is a clear distinction from impact bonds, which seek to integrate innovation into the entire process of problem solving — from establishing collaborations to designing risk-sharing financial arrangements.

One of the most obvious differences between the two bonds is the “demonstration” aspect of this first EIB. Its purpose is to prove green infrastructure for water management and the impact bond as a model for financing impactful solutions. On the other hand, green bonds have become much more common, with almost $75 billion issued in 2016, up from $42.2 billion in 2015.xi Gothenburg’s green bonds are tested and funding multiple projects.

The End Game

These bonds represent two alternatives to mobilizing private investment to achieve environmental and social objectives. As the Rockefeller Foundation stresses, this effort is “critical, because philanthropy and government only have billions to spend, while private markets hold an estimated $210 trillion.”xii This is not an insignificant point for nature either. It is dependent on all parties delivering sustainable results.

i UN Water, Fact Sheet on Climate Change

ii Impact investments are investments made into companies, organizations, and funds with the intention to generate social and environmental impact alongside a financial return. See also: The Core Characteristics of Impact Investing, the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN).

iii Establishment of the Social Impact Investment Taskforce, headed by Sir Ronald Cohen by the UK during the 2013 G8 Social Impact Investment Forum. Concentrated efforts by the Taskforce served as a significant catalyst in rapidly mainstreaming the concept of ‘impact investment’ and the development and maturing of innovation in a wide variety of investment models along what was called the “Impact Investing Spectrum” — from corporate investment in social and environmental initiatives and enterprises to optimising the areas for application of more traditional models of philanthropy.

iv Impact Investing Emerges as a Distinct Asset Class. See also JP Morgan Report: Impact Investing: An Emerging Asset Class.

v GIIN.

vi Respondents are comprised of fund managers (60%), foundations (13%), banks (6%), development financial institutions, family offices and pension funds/insurance companies (2-3% each) – p. XI

vii Development Impact Bonds are a type of impact bond aimed specifically at funding international development investments in emerging and frontier markets. Other organizations involved in the Group included the Rockefeller Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Citigroup, USAID, OPIC, Omidyar Network and government agencies such as the Swedish and UK International Development Agencies.

viii “...hence the need for guarantees, early repayment triggers, etc. in many of those early 1.0 models, or indeed the need to find “particular” investors...”

ix Cicero: the Norwegian Center for Interdisciplinary Climate Change Research.

x Investor reporting, City of Gothenburg (English).

xi ClimateBonds.net

xii Innovations in Finance for Social Impact, Judith Rodin, President, The Rockefeller Foundation

About The Author

Julie King is managing director of Galileo Agency, a boutique agency working with companies and civil society organizations in impact areas — such as water, renewable energy, and the environment — to commercialize products, initiatives, and impact strategies.

Julie King is managing director of Galileo Agency, a boutique agency working with companies and civil society organizations in impact areas — such as water, renewable energy, and the environment — to commercialize products, initiatives, and impact strategies.