The Climate Game-Changer

Part III in the series “Extreme Events And Water Management In The Lower Missouri River Basin.” For background, read Part I and Part II.

By Katy Lackey, research specialist, Water Environment Research Foundation (WERF)

In Part II of this series, experts in the region revealed that tensions in the Lower Missouri River Basin (LMRB) are not what they appear to be. Discrepancies between legal doctrines have little influence over basin-wide management. Conflict primarily arises within states or between states and the federal government. Changing climates, however, may be a game-changer for interstate conflict. Three findings from experts in the region merit further study.

In Part II of this series, experts in the region revealed that tensions in the Lower Missouri River Basin (LMRB) are not what they appear to be. Discrepancies between legal doctrines have little influence over basin-wide management. Conflict primarily arises within states or between states and the federal government. Changing climates, however, may be a game-changer for interstate conflict. Three findings from experts in the region merit further study.

This is the final part in a series exploring allocation conflict during drought in the LMRB. The basin was part of a collaborative workshop series in 2012/2013 exploring strategies and lessons learned from water utilities during extreme events. In the culminating report[i] on these workshops, the Water Environment Research Foundation (WERF) and partners noted competing policies as a potential challenge for basin-wide management.

1. Uncertain changes in water supply.

Experts agreed that the sheer size of the Missouri River coupled, with sufficient regional precipitation (despite periods of drought), is a significant reason why no water allocation conflict has occurred between Kansas and Missouri.[ii] In fact, a joint meeting in 2013 between water utilities in Kansas City divulged little concern over scarce water, even during dry conditions.[iii]

One water utility reports that with an annual diversion of 110,000 to 120,000 acre-feet (AF), it is one of the larger users of the Missouri River in Kansas. It has never required this full allotment, but if it did, it would only lower the Missouri River by .5 percent, or about a tenth of an inch.[iv] Another expert confirms this, as utilities reported more than adequate water availability from a variety of intakes during the 2012/2013 drought.[v]

But the LMRB lies on what experts call the “climate cusp,” a region where climate projections collide and uncertainty is higher. The intersection of two climate regions – projected increases in precipitation for the northern half of the U.S. and decreases for the southern half – occurs in the LMRB.[vi] Future water projections at a local scale are difficult in such cases.[vii] Given the uncertainty surrounding the impact of climate change on water supplies in the LMRB, there is disagreement among experts on the trend in frequency, severity, and the variability of extremes.

Some experts insist extremes are nothing new. The history of flood and drought cycles is vast. The driest year on record can quickly change to the wettest, which is precisely why the USACE built reservoirs on the Missouri River.[viii] The 2011 Flood followed by the 2012/2013 drought is a strong example, though hardly a single occurrence. Others argue that climate trends are changing. That despite the 2012/2013 drought, there is a general upward precipitation trend throughout the basin.[ix]

While some say the drought was unusual, others push back asserting, “everything is relative.” Though the 2011 flooding set an historical record, people have only been keeping records for 100 years. A Kansas Geological Survey study of tree ring data reveals periods of wet weather and drought dating back to the 1500s, suggesting that compared to historical droughts, today’s “look like child’s play,” and the worst is yet to come.[x]

Legal frameworks differ for states within the LMRB, but experts say most utilities work to ensure a sound water supply through many of the same means. This includes building reservoirs, drilling new wells, conservation, and interconnecting existing systems.[xi] Overall, users have been “blessed with pretty strong water supply on both the Kansas and Missouri Rivers” in the past. Some utilities in Kansas City have yet to experience a drought severe enough to witness the full enactment of priority permits under their governing doctrine.[xii]

But the worst may be yet to come, and experts agree there is a need for more resilient management systems in the face of climate uncertainty. For many states in the larger Missouri Basin region, interim agreements during extreme events have provided sufficient relief. Prolonged and reoccurring droughts within short time periods, however, could alter this. When conservation or infrastructural methods are not alone sufficient, the potential for scarcity may require states to reduce water rights through a compact that allocates water resources among multiple sovereigns.[xiii] For an area with multiple governing structures, like Kansas City, state officials would step in to mediate emergency allocations during shortages, utilizing permit numbers coupled with a “pecking order” prioritizing use.[xiv]

2. Invoke full assertion of water rights.

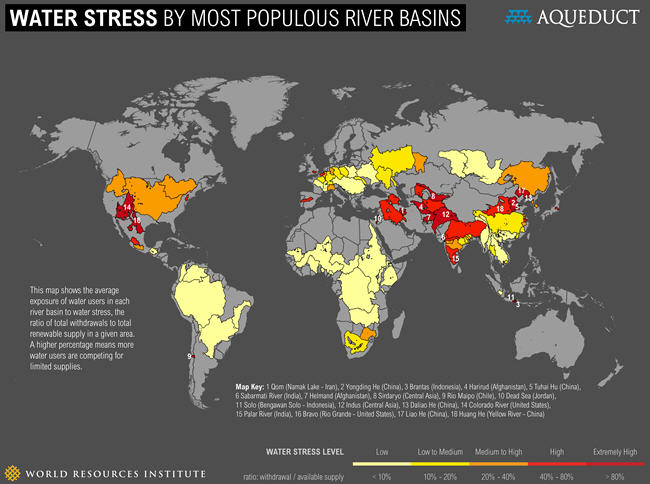

Water availability also depends on factors beyond precipitation and climate projections. Increased population growth in cities, irrigation, and navigation all demand more water. These already contribute to rising water stress in most of the mid-western U.S. (see Figure 3-1). Experts confirm that demand could influence future conflicts in the LMRB, even between states. One puts it: “you create a drought by increasing demand, and demand is certainly not going down. We’ve already seen this on the Colorado River. Missouri hasn’t seen that demand in quite the same way because we haven’t had that extensive agriculture, and irrigated water hasn’t been that important…. yet.”[xv]

Figure 3-1. Medium to high water stress in the Midwest United States.

Source: WRI Aqueduct (http://www.wri.org/blog/2014/03/world%E2%80%99s-18-most-water-stressed-rivers).

Tribal rights supersede all other rights. This often veiled demand poses a significant potential to challenge water supplies. Twenty-eight tribal nations live within the Missouri River Basin that have yet to fully exercise their rights.[xvi] If exercised, this would challenge the “pecking order” between other sovereigns.[xvii] In the event of more extreme and/or reoccurring droughts, tribal communities may be more inclined to step forward and claim their right to water.

3. Exacerbate existing environmental concerns.

The push towards basin-wide planning and Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) draws attention towards the impact municipal and state actions have on downstream users. This includes non-human users (i.e. aquatic ecosystems and surrounding environments), and is becoming an issue in the LMRB. Operational conflicts on the Missouri River are already more fueled by endangered species protection than between human users.

A recent federal-ordered Biological Opinion of the Missouri River placed two birds and one fish species under protection. The USACE-authorized release restrictions during the 2012/2013 Drought severely affected water levels for these species.[xviii] Lower water levels affected overall water quality in the LMRB. This pressured already threatened ecosystems, while also raising treatment costs at municipal intakes, in addition to pumping costs from low levels.[xix] Though temporary, reoccurrences of this will increase stress on water utilities in both Kansas and Missouri.

Others argue riverbed degradation is the most pressing issue in the LMRB.[xx] In areas where the issue is severe, releases can trigger additional degradation. If the riverbed drops, the entire elevation of the Missouri River drops. Though primarily a tension between states and the federal government, over time this could increase the potential for conflict between users. Severe degradation may jeopardize intake operations for utilities, leading to conflicts over allocation previously unseen in the LMRB.[xxi] One utility manager reports, “what would keep me up at night is more the riverbed degradation and the endangered species operation rather than being concerned about allocating the river to users.”[xxii]

[i] Beller-Simms, N., E. Brown, L. Fillmore, K. Metchis, K. Ozekin, C. Ternieden, and K. Lackey. 2014. Water/Wastewater Utilities and Extreme Climate and Weather Events: Case Studies on Community Response, Lessons Learned, Adaptation, and Planning Needs for the Future. Project No. CC7C11 by the Water Environment Research Foundation: Alexandria, VA.

[ii] Personal Informal Interview, November 2013.

[iii] Personal Informal Interview, November 2013.

[iv] Personal Informal Interview, November 2013.

[v] Personal Informal Interview, November 2013.

[vi] Beller-Simms et al., 2014.

[vii] Beller-Simms et al., 2014; Solomon, S.; Qin, D.; Manning, M.; Chen, Z.; Marquis, M.; Averyt, K.B.; Tignor, M.; Miller, H.L. (eds). 2007. Summary for Policymakers. Technical Report in Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovermental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1-18.

[viii] Personal Informal Interview, November 2013.

[ix] Personal Informal Interview, November 2013.

[x] Personal Informal Interview, November 2013.

[xi] Personal Informal Interview, November 2013.

[xii] Personal Informal Interview, November 2013.

[xiii] Matson, J.T. 2012. Interstate Water Compact Version 3.0: Missouri River Basin Compact Drafters Should Consider an Inter-Sovereign Approach to Accommodate Federal and Tribal Interests in Water Resources. North Dakota Law Review, Vol 88: 97, 97-138.

[xiv]Personal Informal Interview, November 2013.

[xv]Personal Informal Interview, November 2013.

[xvi] Beller-Simms et al., 2014;

[xvii] Personal Informal Interview, November 2013.For more information, please see Capossela, P. 2002. Indian reserved water rights in the Missouri River Basin. Great Plains Natural Resources Journal, 6, 131-189 or Davidson, J.H. 1999. Indian Water Rights, the Missouri River, and the Administrative Process: What are the Questions? American Indian Law Review, 24, 1-493.

[xviii] Personal Informal Interview, November 2013.

[xix] Beller-Simms et al., 2014.

[xx] Personal Informal Interview, November 2013.

[xxi] Personal Informal Interview, November 2013.

[xxii] Personal Informal Interview, November 2013.