Floods Breed Cooperation, Droughts Breed Conflict

Part I of III in the series “Extreme Events And Water Management In The Lower Missouri River Basin”

By Katy Lackey, research specialist, Water Environment Research Foundation (WERF)

If the wars of this century were fought over oil, the wars of the next century will be fought over water.i Resonating throughout the hotly debated water wars thesis of the late ’90s, these words reflect rising water demands in recent decades. Populations around the world are swelling. Higher contamination levels threaten water quality in some areas; dwindling supplies challenges water quantity in others. Recent fluctuations in extreme events — floods, hurricanes, droughts, atmospheric rivers — merely exacerbate these issues.ii Communities grapple with worsening, and sometimes new, water management issues. This increasingly dismal state of the world’s water raises awareness that the resource we once used so freely may bring a slew of costs in the future.

If the wars of this century were fought over oil, the wars of the next century will be fought over water.i Resonating throughout the hotly debated water wars thesis of the late ’90s, these words reflect rising water demands in recent decades. Populations around the world are swelling. Higher contamination levels threaten water quality in some areas; dwindling supplies challenges water quantity in others. Recent fluctuations in extreme events — floods, hurricanes, droughts, atmospheric rivers — merely exacerbate these issues.ii Communities grapple with worsening, and sometimes new, water management issues. This increasingly dismal state of the world’s water raises awareness that the resource we once used so freely may bring a slew of costs in the future.

In the mid-western United States, the Lower Missouri River Basin (LMRB) is no stranger to extreme climate/weather events. Like many communities around the world, the basin finds itself dealing with excess water one year, and too little the next. Balancing water allocation and management is more and more difficult. Communities and systems have little time to recover before another disaster hits.

Time and again, scholars undercut the notion of water wars thesis. Critics argue there is more evidence that water shortages or stress encourage cooperation, not conflict.iii Amidst decades of war, for example, the five riparian states of the Jordan River Basin have reached widespread cooperation in establishing water agreements. People may do terrible things, but will they deny their neighbor water? Water is, after all, our “lifeblood resource,” the “arteries of our planet.’ But it is also ignorant of political boundaries. Around 263 of the world’s rivers and lakes are transboundary; 90 percent of the global population resides within these boundaries.iv

The push for integrated water resource management (IWRM) is growing stronger, and perhaps signifies cooperation prevailing over conflict. Basin-wide management and planning efforts across political borders are more and more common. Though we have yet to witness a full-fledged “war over water,” history is resplendent with various water conflicts. And as communities explore ways to work together, competing uses, laws, and policies challenge their success.

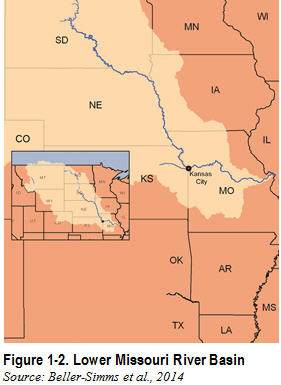

Spanning five states — parts of Wyoming, Nebraska, Kansas, Iowa, and Missouri — the LMRB represents a challenging case for basin-wide management (Figure 1-2). It is one of many basins experiencing an upward trend in extreme events. The Water Environment Research Foundation (WERF), in collaboration with several other organizations, held a series of workshops in 2012/2013 to better understand the strategies and lessons learned of water management during extreme events.v During the LMRB workshop in Olathe, KS, participants expressed that perhaps some truth lies in the claim that “floods breed cooperation; droughts breed conflict.”vi

Spanning five states — parts of Wyoming, Nebraska, Kansas, Iowa, and Missouri — the LMRB represents a challenging case for basin-wide management (Figure 1-2). It is one of many basins experiencing an upward trend in extreme events. The Water Environment Research Foundation (WERF), in collaboration with several other organizations, held a series of workshops in 2012/2013 to better understand the strategies and lessons learned of water management during extreme events.v During the LMRB workshop in Olathe, KS, participants expressed that perhaps some truth lies in the claim that “floods breed cooperation; droughts breed conflict.”vi

Floods provoke acute, emergency response where communities focus on helping one another. We see these cooperative efforts following events such as Hurricanes Sandy and Katrina. In times of excess water, it’s first about saving lives and assets. Prolonged dry conditions on the other hand, require sustained response actions. Efforts suddenly become about a fight to maintain our current way of life. When there is not enough water to go around, localities must determine the best allocation of threatened water supplies. Water utilities must manage competing user needs while upholding water quality, quantity, and discharge regulations — a feat that is only becoming more challenging.

In just 20 years, the LMRB experienced two 100-year floods (1993 and 2011) followed by a severe drought. During the 2012/2013 drought in the basin, the Missouri River dropped from a 9x300-foot channel to 8x200 feet, with reduced support for navigation and over $500 million in crop loss.vii Participants in WERF’s 2012 workshop noted that this “ignited tension over water supplies and river flows in a region that traditionally perceives itself as having plenty of water.”viii Is this enough to cause real conflict in the basin? To understand existing or potential conflict, one must dig deeper into sources of tension.

Aside from floods and droughts, political boundaries in the basin pose a challenge for water management through conflicting systems of water governance. Straddling both Kansas and Missouri states, an invisible border runs through Kansas City that signifies the geographical collision of two major laws that historically govern water in the U.S. Water from the Missouri River flows freely through this border, marking the division between states that subscribe to the prior appropriate doctrine with those that follow the riparian doctrine. Participants at WERF’s workshop noted the importance of these variable state water laws in water management, particularly during prolonged drought. Perceptual differences in water rights, arising from the two governing laws may cause tension between different stakeholder groups, impacting the institutional capacity of utilities to effectively manage community expectations and responses to extreme events.ix

The variable state water laws begs a larger question of how utilities reconcile low flow levels and competing allocation needs amidst the two seemingly contentious doctrines. Given the shared boundary of water flows, this series examines the emergence of allocation conflict in the basin. Part II explains the legal frameworks governing water in the LMRB, implications during drought, and where conflict exists. This includes information provided during interviews with climate, water, and legal experts in the region. Part III dives deeper into findings from experts and what may challenge these.

iIsmail Serageldin in 1995, then Vice President of Special Programs at the World Bank. Mr. Serageldin was not the first, nor the last to state this.

iiBeller-Simms, N., E. Brown, L. Fillmore, K. Metchis, K. Ozekin, C. Ternieden, and K. Lackey. 2014. Water/Wastewater Utilities and Extreme Climate and Weather Events: Case Studies on Community Response, Lessons Learned, Adaptation, and Planning Needs for the Future. Project No. CC7C11 by the Water Environment Research Foundation: Alexandria, VA.

iiiCenter for World Dialogue. 2013. Water: Cooperation or Conflict? Global Dialogue, Vol. 15, No. 2. http://www.worlddialogue.org/issue.php?id=53 (accessed: December 1, 2014).

ivUN Water. 2008. Transboundary Waters: Sharing Benefits, Sharing Responsibilities. United Nations Water, Geneva Switzerland. www.unwater.org/downloads/UNW_TRANSBOUNDARY.pdf (accessed: December 1, 2014).

vBeller-Simms et al., 2014.

viBeller-Simms et al., 2014.

viiBeller-Simms et al., 2014.

viiiBeller-Simms et al., 2014.

ixBeller-Simms et al., 2014.