7 Steps To Water System Asset Management

By Linda Blankenship, Associate Vice President, ARCADIS US, Inc.

A primer on developing asset management programs to support economically and environmentally sustainable water systems.

A city that struggles to supply water and treat wastewater is a city at risk. As critical resources to support a healthy population, water and wastewater underpin so many of the things that make a city sustainable, from agriculture and industry to energy and economic development. For this reason, cities that tackle water issues will find themselves at the top of the list of most sustainable, successful communities.

Priority Planning

On many levels, water system asset management is a cornerstone of sustainability and resiliency, supporting the insights, planning, and day-to-day discipline needed to optimize these both operationally and financially over the long-term. However, for water utilities seeking to manage sustainable systems, the challenges are all too familiar and usually start with budget struggles.

The tension between immediate needs and long-term imperatives can quickly derail asset management planning before it starts. Aging infrastructure competes with new construction for investment funds, making for some “apples and oranges” debates, like how to balance the need to renew old systems and also install new tunnels to manage combined sewer overflow (CSO). And what happens when the system becomes so patched and aged that you can no longer stay ahead of the failures? Reactive maintenance and repair is the most expensive and inefficient approach that a utility can undertake.

Funding is only one issue. The other is often information. It isn’t really planning if you have no way to know what the effects of your actions will be. Information technology can provide some answers, but data sets may be incomplete or out of date. Leading approaches and practices of asset management can help bring the whole picture into focus, with benefits across operations, ultimately enhancing customer acceptance and stakeholder support.

In fact, at its fundamental core, asset management planning helps optimize the life-cycle cost of assets, while meeting levels of service that customers and other key stakeholders desire. But that doesn’t make it any easier to get started. It can be as challenging to justify the cost in both time and funding to develop and implement an asset management plan as it is in any capital project.

Sometimes it’s easier to get buy-in by demonstrating success on a small scale as a proof of concept. Fortunately, there are some ways to start small while also building the case for a comprehensive program.

Stepping Up (x7)

1. Produce quick and efficient focus with gap analysis. Every utility starts with some elements of an asset management program in place. Gap analysis, comparing current and leading best practices, helps define the best opportunities to improve levels of practice in select areas. It’s about taking one step at a time and finding the most efficient path forward to improve. Almost any gap analysis will define “quick wins” (programs that can be accomplished within a year with resources generally available). Quick wins help to achieve a feeling of accomplishment and momentum toward the next and perhaps more challenging phases of the project.

2. Creatively use existing asset and performance data. Existing data within a utility is often underutilized. But this data will be gold when it comes time to gain public, governmental, and financial support. Tools available today can quickly and easily pinpoint the availability and completeness of basic asset attribute data. Even if key data is missing, it’s still possible to creatively gather, supplement, and leverage existing data for planning. For example, analyzing pump flow and related SCADA (supervisory control and data acquisition) data can help identify inefficiencies and opportunities for energy savings, which in turn can translate into funding for other program initiatives. Water main break data is commonly available and can be used to predict future performance and reduce the risk of critical failures.

3. Review and set levels of service with future improvements in mind. Setting levels of service can make a big impact in operational demands. A maximum two-hour outage can have you scrambling, whereas a four-hour outage may be acceptable. Seemingly modest adjustments in these water and sewer service goals can greatly affect resources as well as operations and capital investment strategies. Alternatively, the long-range plan may start with manageable goals but with milestones in place to step up to more ambitious levels of service.

4. Analyze and plan to manage the risks. Risk is fundamentally about the consequence and likelihood of failure, typically calculated using a point scale. Consequence of failure is often based on triple-bottom-line principles for economic, social, and environmental impacts. Examples include direct cost to repair, proximity to sensitive receiving waters, critical customer outages, road closures, and similar considerations that can usually be readily mapped.

Likelihood of failure should be based on consideration of the four possible failure modes: mortality, efficiency, level of service, and capacity. For example, a mortality failure is one in which the asset is physically incapable of performing its function, such as a sewer main collapse. The consequences of this might produce multiple impacts, depending on the situation. If raw sewage reaches a waterway or a nearby waterbody, it could impact public health. If it runs under a street, the failure could cause traffic delays. Economic consequences could follow seepage into water or buildings.

An efficiency failure results when there are more cost-effective and feasible alternatives, such as opting for inefficient equipment motors with high energy costs. In this case, the consequence is generally economic. Level-of-service issues related to an asset failure, as compared to an enterprise-wide level of service, could include a pump that cannot achieve the required wastewater flow during peak demand times. The consequence of failure could be sewer overflows that result in fines and negative environmental impacts. Capacity failure could include a pump that cannot provide adequate water supply during peak periods, resulting in reduced revenue.

5. Develop a prioritized plan. Fundamentally, asset management is about change management. Change management takes time. Therefore, it makes sense to develop a prioritized plan so that staff has the opportunity to do their “day job” and still participate meaningfully in the development of the asset management program. It’s important to adapt practices to fit within one’s own utility — again, that takes time. Most utilities take between three to five years to make significant progress with the development of their asset management program. Whether you use the U.S. EPA 10-step process or the newly adopted ISO 55000 standard, the core concepts of managed risk, planned service levels, and life-cycle cost are still important components.

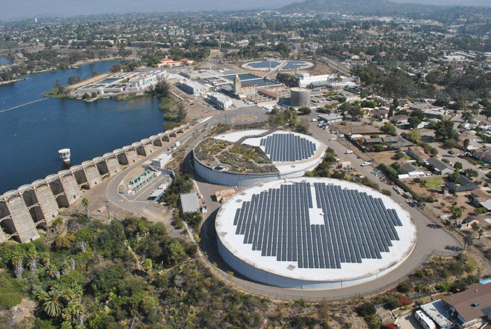

Like many top municipalities, the City of San Diego, CA, which operates the Alvarado Water Treatment Plant (pictured), relies on asset management to inform decision-making.

6. Create a holistic, connected picture of operations and capital needs. One of the more significant insights that asset management creates is the need to manage the life-cycle cost of assets — from planning, design, and construction through the often long operational cycle. A capital investment today can be a decision that a utility lives with for a long time. So practices that connect the two, even if they reside in separate budgets, will yield benefits down the road. Simply put, a cheap capital investment today can be a high operating expense through a lot of tomorrows.

7. Implement the plan and measure results. As the old saying goes, “You can’t manage what you don’t measure.” Some key performance indicators really help gauge progress or make visible how changes are driving performance improvements. For instance, the percentage of planned maintenance work orders completed compared with the ones scheduled for critical valves and pumps can be a leading indicator of whether there might be issues with achieving a level of service of 100 percent of customers with no water outages of greater than two hours. It’s important to track progress and trends to know what areas need to be improved and which ones can wait.

Managed Risk And The Reward

At its core, asset management can be seen as a matter of managed risk, no matter what the asset is. Utility managers who do the hard work of advancing the level of practice of asset management will ultimately leave their utility more sustainable for the future.

For example, in a project managed by the Water Environment Research Foundation1, the authors found that best practice utilities routinely (at least annually) sought to identify the “big picture” risks to the operations. They developed a risk register and discussed these risks with their elected and appointed officials, then senior leadership developed plans to manage these risks. The risks that they considered were broad, from natural disaster risks, such as flooding and earthquakes, to man-made risks, such as labor issues, healthcare costs, or the impact of a disgruntled employee who wants to sabotage control systems.

In the end, once started, asset management quickly brings benefits that become essential. It improves financial performance, efficiency, and effectiveness; manages risk; informs asset investment decisions; and improves reputation, compliance, and sustainability.

References

1. “Leading Practices For Strategic Asset Management,” by Linda Blankenship, Frank Godin, Terry Brueck, EMA, Inc. Published by the Water Environment Research Foundation. 2012.

About The Author

Linda Blankenship is Associate Vice President with ARCADIS US, Inc. She was the principal investigator and program manager for the WERF research challenge “Strategic Asset Management Implementation and Communication,” developing leading practices, tools, and guidance. Linda has more than 25 years of experience working on a wide variety of drinking water, wastewater, groundwater, and stormwater issues, holding senior positions while managing major infrastructure planning in local government as well as managing regulatory affairs, technical programs, and research support in major water industry associations.

Linda Blankenship is Associate Vice President with ARCADIS US, Inc. She was the principal investigator and program manager for the WERF research challenge “Strategic Asset Management Implementation and Communication,” developing leading practices, tools, and guidance. Linda has more than 25 years of experience working on a wide variety of drinking water, wastewater, groundwater, and stormwater issues, holding senior positions while managing major infrastructure planning in local government as well as managing regulatory affairs, technical programs, and research support in major water industry associations.