'Project Clean Lake' Breaks New Ground In Pollution Control

By Michael Uva, senior communications specialist, Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District

The Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District’s $3 billion pollution-control plan includes massive and lengthy tunnels but goes the extra mile by adding advanced wastewater treatment.

In 1972, the Clean Water Act was created to address the nation’s water-quality issues, among them the foul spectacle of raw sewage discharging into the environment. In Cleveland, the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District’s construction projects during the following decades would reduce these discharges significantly — from an estimated 9 billion gallons a year down to 4.5 billion in 2013.

However, in 1994, the U.S. EPA adopted a Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) Control Policy, which required wastewater agencies to develop long-term CSO-control plans to further reduce overflow. Cleveland and hundreds of cities around the country have negotiated long-term plans with the EPA to address sewage overflows.

Fighting Overflow

Why do overflows occur? The combined sewers prevalent in older cities carry both sewage and stormwater. When heavy rains overload the combined sewers, relief points within the sewers (known as regulators) allow the untreated stormwater and sewage to overflow into area waterways to avoid backups and home and street flooding. This CSO contains bacteria from human waste, industrial waste, and other pollutants swept from the ground’s surface. Following rain events, Cleveland’s beachgoers are often advised not to go swimming in Lake Erie due to elevated bacteria levels that accompany CSOs.

Project Clean Lake is the sewer district’s $3 billion, 25-year program to reduce the total volume of CSOs in Cleveland from an estimated 4.5 billion gallons annually to less than 500 million gallons. By 2035, the number of overflows will be reduced to four or fewer per year, resulting in an estimated 98 percent capture and treatment of all wet-weather flows in Cleveland’s combined sewer system.

At the heart of Project Clean Lake is the construction of seven large-scale storage tunnels, ranging from two to five miles in length, up to 300 feet underground, and up to 24 feet in diameter — large enough to fit a semi-trailer truck. This technology is widely used in CSO-control plans across the country. The tunnels can hold tens of millions of gallons of CSO, rather than allowing it to discharge into Lake Erie and the Cuyahoga River. After the rain stops, massive hydraulic pumps convey the flow back to the surface and to one of the district’s three wastewater treatment facilities.

In April 2011, the sewer district broke ground on its Euclid Creek Tunnel project, which includes an 18,000-foot-long, 24-foot-wide storage tunnel 200 feet underground. Just over two years later, in August, 2013, “Mackenzie,” the district’s 1,500-ton tunnel boring machine, completed its three-milelong excavation. The finished tunnel will have the capacity to capture about 65 million gallons of combined wastewater and stormwater and will directly impact water quality in Lake Erie and local streams.

Project Clean Lake also includes a minimum of $42 million in green infrastructure projects, which the federal government had never before included in its CSO-control consent decrees. These stormwater-control measures, which include such technologies as bioswales and detention basins, can store, infiltrate, and evapotranspirate rainfall before it even makes its way into the combined sewer system. In the last five years, the sewer district has committed more than $31 million to green infrastructure projects.

Plant Power

Enhancements to the sewer district’s three wastewater treatment plants, which together treat over 90 billion gallons each year, are crucial components of Project Clean Lake. At the district’s Easterly and Southerly treatment plants, the amount of wastewater that can receive treatment will increase. This is necessary to accommodate the greater volumes of combined flow that will no longer be allowed to discharge straight into the environment. In particular, the Easterly plant is undergoing major construction through 2016 to expand its secondary treatment capacity, including the installation of six additional final settling tanks.

Despite the ongoing construction, Easterly was recognized in 2014 with the highest performance honor from the National Association of Clean Water Agencies: the Platinum “Peak Performance” Award, for five consecutive years of meeting National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits. The Westerly and Southerly plants also received Gold Awards for continued excellence in meeting their NPDES permits.

Despite the ongoing construction, Easterly was recognized in 2014 with the highest performance honor from the National Association of Clean Water Agencies: the Platinum “Peak Performance” Award, for five consecutive years of meeting National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits. The Westerly and Southerly plants also received Gold Awards for continued excellence in meeting their NPDES permits.

In addition, all three district plants are implementing advanced methods for dealing with wetweather flows from overwhelming rain events. “Even with the new storage tunnels, you still can have overflow,” explained Douglas Dietzel, a process specialist at the Westerly plant. “So, as part of our agreement with the EPA, we’re increasing our ability to treat wastewater during highflow events.”

The Westerly plant, which sits on the shore of Lake Erie, is Cleveland’s oldest wastewater treatment site (constructed in 1922) and serves approximately 103,000 residents. The plant processes an average flow of 26 million gallons per day (MGD) of wastewater, and its Combined Sewer Overflow Treatment Facility (CSOTF) provides storage for six million gallons and preliminary treatment for up to 300 MGD during wet-weather flows. In the CSOTF, the heavier organic material is allowed to settle out of the wastewater, but the flow can still contain pathogens when it is returned to Lake Erie, since it does not pass through secondary treatment or disinfection.

Chemically Enhanced Treatment

A new project, called Chemically Enhanced High Rate Treatment (CEHRT), will expand the overall size and scope of the treatment process with the inclusion of chemical storage and feed facilities, providing treatment and disinfection capabilities absent from the current system.

CEHRT is actually two acronyms combined: Chemically Enhanced Primary Treatment (CEPT) and High Rate Disinfection (HRD). CEHRT is an advanced way of treating wastewater overflow by speeding up the natural, gravity-based settling process used in the normal treatment process (through the addition of chemicals) and providing disinfection.

“Coming into the plant is all this negatively-charged organic material,” explained Dietzel. “We neutralize that charge with ferric chloride, which has a positive charge. Then we use an anionic polymer, a long chain of hydrocarbons, to stick to all of those suspended particles.” The polymer creates a “floc,” meaning that the suspended organic particles clump together and settle out of the water. The flow then goes to the HRD tank, where sodium hypochlorite, a strong bleach, is added to kill off any remaining pathogens. “Instead of having just settled wastewater, you have treated flow safely going back out into the lake,” said Dietzel.

“Coming into the plant is all this negatively-charged organic material,” explained Dietzel. “We neutralize that charge with ferric chloride, which has a positive charge. Then we use an anionic polymer, a long chain of hydrocarbons, to stick to all of those suspended particles.” The polymer creates a “floc,” meaning that the suspended organic particles clump together and settle out of the water. The flow then goes to the HRD tank, where sodium hypochlorite, a strong bleach, is added to kill off any remaining pathogens. “Instead of having just settled wastewater, you have treated flow safely going back out into the lake,” said Dietzel.

The EPA gave the district an opportunity to demonstrate the effectiveness of lowercost treatment options like CEHRT through pilot demonstration projects. If successful, the district would be able to avoid implementation of the more costly ballasted flocculation treatment technology. “The EPA initially wanted us to use a much more expensive sand-injection process,” said Dietzel. “They gave us three years to test out CEHRT at all three of our plants, and if it worked we could use it.”

The EPA gave the district an opportunity to demonstrate the effectiveness of lowercost treatment options like CEHRT through pilot demonstration projects. If successful, the district would be able to avoid implementation of the more costly ballasted flocculation treatment technology. “The EPA initially wanted us to use a much more expensive sand-injection process,” said Dietzel. “They gave us three years to test out CEHRT at all three of our plants, and if it worked we could use it.”

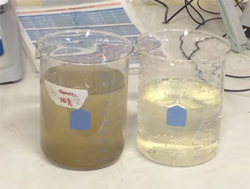

The plants have utilized a bench test to determine the optimum amounts of ferric chloride and polymer to get the process to work. “Based on our testing, we see that CEHRT works very well,” said Dietzel, noting the contrast between the brown, muddy wastewater and the clear, post-CEHRT effluent. If given the go-ahead by the EPA, the CEHRT systems could be fully operational at all three district plants as early as December 2021.

Project Clean Lake means a cleaner Lake Erie. But, with a $3 billion price tag, it also means that rates will increase. As the district’s main source of revenue, customers’ sewer-bill payments will fund these construction projects and plant enhancements, and rate increases will be significant. The success of the CEHRT pilot program, and opportunities to optimize projects through advanced planning and value engineering, will help the district minimize Project Clean Lake’s financial impact on its ratepayers. “The CEHRT system is relatively new, and very few wastewater agencies in the U.S. use it,” said Dietzel. “We are the first large sewer authority to do something like CEHRT. It will save our ratepayers money, and that’s our goal.”

About The Author

Michael Uva is the senior communications specialist at the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District.