Industrial Water Treatment For Inorganic Contaminants: Regulatory Drivers

By Mark Reinsel, Apex Engineering

By Mark Reinsel, PhD, PE, Apex Engineering, PLLC and Scott Mason, PG, Hydrometrics, Inc.

This article is the first in a series on industrial water treatment focusing on inorganic contaminants. A logical starting point is to examine the regulations that determine (or are interpreted to determine) an industrial facility’s discharge limits. These limits then form the basis for all of the water treatment work that follows. That water treatment work will be the focus of subsequent articles in Water Online.

The goal of this article is to summarize the process of how industrial discharge limits are established. These discharge limits (effluent limits) allow the environmental professional to then specify treatment goals and process design criteria.

Source of Limits

Regulatory limits come from four main programs:

- For point source discharges to surface water, National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits or the state equivalent;

- For groundwater discharges, the appropriate state program;

- Underground injection control program (EPA or state); and

- Nonpoint source controls such as total maximum daily loads (TMDLs) or best management practices (BMPs).

This article will focus on the first program, NPDES permits. NPDES permits are generally required for discharge of pollutants from any point source into “waters of the U.S.” An NPDES permit is essentially a license or contract for discharge of specified amounts of pollutants into a water body under specified conditions. Exceeding those specified amounts or conditions may bring legal and/or financial ramifications.

A point source is any discernible confined and discrete conveyance from which pollutants are or may be discharged. Examples include pipes, ditches, leachate collection systems, and publicly owned treatment works (POTWs).

The term “waters of the U.S.” (or State) covers a broad range of surface waters and may include hydrologically connected groundwater. This subject has been the subject of numerous court cases.

Conditions specified in each NPDES permit are typically:

- Effluent limitations, including flow rate, concentrations, pollutant load, and toxicity.This section is the “meat” of the permit.

- Special conditions such as mixing zones and compliance schedules.

- Monitoring requirements.

- Prohibitions (e.g., bypass of treatment).

- Conditions under which the permit may be re-opened (“re-opener”) and report of changes.

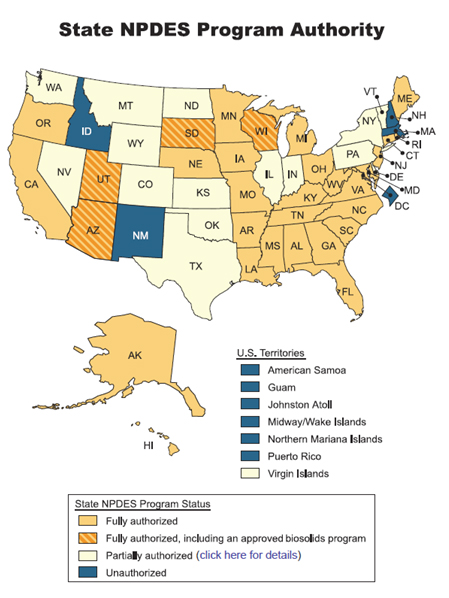

The figure below shows the administration of NPDES programs in U.S. states and territories. “Fully authorized” means that the federal government (EPA) has delegated complete NPDES control to those states, while “unauthorized” means EPA maintains NPDES control in those states. Many states are only “partially authorized.” Authorized states often rename the program; for example, Montana has a Montana Pollutant Discharge Elimination Program (MPDES).

A common source of information is the NPDES Permit Writers’ Manual (EPA, 2010).

A pollutant is defined as “any type of industrial, municipal, or agricultural waste (including heat) discharged into water…” Common pollutants include:

- Conventionals (e.g., biochemical oxygen demand or BOD, total suspended solids or TSS, oil and grease or O&G, pH)

- Nonconventionals (e.g., chlorine, ammonia, chemical oxygen demand or COD)

- Toxics (e.g., metals, organic chemicals and other priority pollutants)

- Nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus)

- Radiological

- Asbestos

- Heat

Permit Limits

NPDES permit limits are based on two types of effluent limits. The first is technology-based effluent limits (TBELs). The second type of effluent limits is water quality-based effluent limits (WQBELs), which are examined only if required (as discussed below).

Permit limits will be the lower of TBELs and WQBELs, plus a margin of safety (MOS). The MOS is based on variations in treated water quality, the sampling frequency and the specific permit limit statistic (e.g., “maximum daily,” “average monthly,” “acute vs. chronic”). After permit limits have been determined, the environmental professional will likely include an additional MOS in the goals/design criteria for the water treatment process.

TBELs are the maximum effluent concentrations (e.g., mg/L) and/or pollutant loads (e.g., lbs/day) that may be discharged. These limits are required regardless of the effect of the discharge on receiving waters, and are based on applying specified levels of technology controls. An example is best available technology (BAT).

The second type of NPDES permit limits is WQBELs, which establish the level of effluent quality necessary to protect water quality and ensure attainment of water quality standards in receiving water. Use of WQBELs is necessary when a “reasonable potential” exists that TBELs alone will not meet water quality standards (EPA, 1991).

WQBELs are based on water quality criteria, adjusted upward or downward by several possible modifiers. Possible upward modifiers, which would create higher water quality limits, are: 1) a dilution allowance (mixing zone) and 2) variances (which are relatively rare). Possible downward modifiers, which would create lower quality limits, are:

- Anti-degradation requirements (which will be discussed later);

- A margin of safety (already discussed);

- TMDL requirements;

- Whole effluent toxicity (WET) requirements; and

- Anti-backsliding.

Water Quality Standards

The required elements of water quality standards include:

- A “use designation” for the water body (e.g., designating it as fishable, swimmable, or drinkable).

- Water quality criteria to protect uses.An example is a 10 micrograms/liter (ug/L) arsenic standard for drinking water.

- An antidegradation policy, which is a policy to maintain water quality at or better than water quality criteria.

Water quality criteria are based on four possible user groups:

- Human health (drinking, recreation, fish ingestion);

- Aquatic life (salmonids, non-salmonids, marine, freshwater, vegetation);

- Livestock; and

- Wildlife.

Most water quality criteria are initially developed by EPA as national criteria. These criteria are typically adopted by states and tribes, sometimes with modifications. The criteria are routinely re-evaluated by EPA.

Optional policies to include in developing water quality standards are mixing zones, variances, and critical low flows. These topics are well covered in the NPDES Permit Writers’ Manual (EPA, 2010).

Anti-degradation

Various U.S. states term this either “anti-degradation” or “nondegradation.” It is defined as “Where the quality of the waters exceed levels necessary to support (beneficial uses) … that quality shall be maintained and protected unless … allowing lower water quality is necessary to accommodate important economic or social development in the area in which the waters are located.”

Anti-degradation policy allows the discharge to use only a portion of the “assimilative capacity” of the water, i.e., its capacity to receive pollutants without harmful effects and without damage to aquatic life or humans who consume the water. The portion allowed depends on the type and strength of the pollutant. For some pollutants (e.g., carcinogens, bioaccumulators, or persistent contaminants), the portion may be zero.

Industrial Discharges

In the big picture, discharge limits depend on the type of water discharged, uses or processes that the water has undergone, the receiving water, and where, when, and how the discharge occurs. As an example of an industrial discharge, discharge limits for mine water will be examined. TBELs can be determined by:

- Finding the NAICS number for the mine type (2122);

- Determining the type of mine water; and

- Looking up Efluent Limitations and Guidelines (ELGs) in 40 CFR Part 440 (or rarely, Part 122).

The several types of mine water to consider are:

- “Mining drainage and beneficiation.”These ELGs are found in 40 CFR Part 440, Ore Mining and Dressing.

- “Refining Wastewater,”whose ELGs are found in 40 CFR Part 421.

- “Stormwater,” which is not covered by ELGs unless commingled with mine drainage or process water.

Subpart J of 40 CFR Part 440 covers copper, lead, zinc, gold, silver, and molybdenum ores. For existing water sources, effluent limit guidelines (ELGs) are a combination of concentrations attainable by 1) best practicable control technology currently available (BPT) and 2) best available technology economically achievable (BAT). These limits depend on the type of wastewater, e.g., “mine drainage,” “froth flotation process wastewater,” etc. Example ELGs are 30-day averages of 20 mg/L for TSS and 0.15 mg/L for copper.

BPT and BAT include “zero discharge” of water in some cases. For example, cyanide leach or copper leach process wastewater may not be discharged except for the amount equal to net precipitation at the site.

For new water sources at copper, lead, zinc, gold, silver, and molybdenum mines, ELGs equal the concentrations attainable by best available demonstrated technology (BADT). Parameters covered and their limits are typically similar to existing sources. BADT also includes “zero discharge” in some cases.

Emerging Contaminants of Concern

Potential emerging contaminants of concern (COCs) include:

- Methylmercury, which is one of EPA’s National Recommended Water Quality Criteria.

- Radon.A maximum contaminant level (MCL) is being developed by EPA.

- Cobalt, molybdenum, strontium, tellurium, and vanadium.All are included in EPA’s Contaminant Candidate List (CCL) 3.

- Sulfate, aluminum, chloride, iron, manganese, and total dissolved solids (TDS).These all currently have secondary drinking water standards.

- Electrical conductivity and sodium adsorption ratio (SAR).These parameters are of concern in coalfield produced water.

For more information, contact Mark Reinsel at http://apexengineering.us or Scott Mason at smason@hydrometrics.com.

See part two in the series, "Selecting A Treatment Process".

References

- U.S. EPA, 2010.NPDES Permit Writers’ Manual.EPA-833-K-10-001.September.

- U.S. EPA, 1991.Technical Support Document for Water Quality-based Toxics Control.EPA/505/2-90-001.March.