Beyond Usability: What It Means To Humanize A Medical Device

By Amy Schwartz, Battelle

Who (or what) is your medical device designed for — the human who will use it, or just the disease you are addressing?

To get regulatory approval, it is understood that medical devices must perform their intended task (e.g., delivering a medication or taking a health measurement) accurately and without compromising the safety of the patient or caregiver. A device designed to monitor the blood sugar level of a patient with diabetes, for example, must provide reliable and accurate blood glucose readings. It must also meet basic human factors criteria to ensure that the intended user can use it safely and effectively.

But these basic requirements are only the beginning. Medical devices are used by human beings with complex emotional and social needs. Designing medical devices that better fit into people’s lives can improve not only user satisfaction, but also adherence with treatment protocols. Ultimately, humanizing medical devices is a path towards better adherence and patient health.

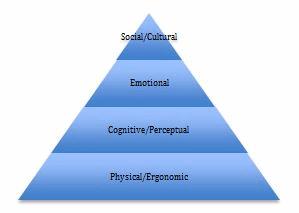

The Medical Device Development Hierarchy of Needs

Anyone who has taken Psychology 101 should be familiar with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs[1]. Maslow’s Hierarchy is commonly illustrated as a pyramid with basic physiological needs (food, shelter) at the bottom and higher needs (safety, love/belonging, esteem, self-actualization) ranked above. Maslow’s insight was that all levels of the pyramid are important for humans, but more basic needs must be met before people have the capacity to seek fulfillment of higher needs.

Each level requires understanding the needs of the users, as well as the context and environment in which they will use the device. Different types of users (children, seniors, patients with impairments related to their condition) may have different needs at each level. Contextual research with the intended user population can help developers better understand these needs. Questions to consider at each level include:

- Physical/Ergonomic — Is the device light enough to be easily held or carried? Does it fit comfortably into the hands? Are buttons or dials easy to reach and manipulate? Is visual information easy to see? How much hand strength is needed to manipulate the device? If it is worn on the body, does it interfere with other activities of daily living?

- Cognitive/Perceptual — Does the device provide physical or visual clues that show me how it is to be held and used (e.g., a depression where the thumb should be placed)? Are visual information or instructions easy to interpret and follow? Does the device provide feedback to let me know when a step is successfully completed, or when another action must be taken? How many steps must I follow, and are they in an intuitive sequence? Do sensory alerts follow established cultural norms (e.g., flashing red lights when something is wrong, a steady green light when the device is ready to use)?

- Emotional — How does the device make me feel when I use it? Does it make me feel sick or vulnerable? Does it make me feel stupid? Does it look intimidating or scary?

- Social/Cultural — If other people see the device, or see me using it, how will it make me feel? Does it make me look weird or different? Am I embarrassed to be seen with this device? How does this device impact the way other people perceive me? Does using the device require breaking any cultural taboos?

Humanizing Medical Devices

Imagine you are a small child getting a CT scan. You are taken to a small white room with bright lights and asked to lie down on a platform. The platform slides into a bare white tunnel, where you can’t see your parents or the nurses. You feel vibrations and hear loud noises that you don’t understand. Someone you can’t see periodically gives you orders without explanations: hold your head still. Don’t breathe for five seconds. Ok, now breathe.

This is a frightening scenario for children, even if they understand the medical necessity of what they are doing. It is notoriously hard to get small children to follow instructions, even more so when they are frightened. For this reason, many children must be anesthetized before entering a CT scanner. But, an engineer at GE figured out a better solution: turning the CT scan into a storybook adventure.

GE designed CT machines with child-friendly “skins” that made them look like pirate ships. Instead of just telling children what to do, the medical staff turn the experience into a story: “OK, time to lie still—the pirates are coming!” In other words, they humanized the experience. Children were less frightened and more willing to follow instructions, and fewer children needed anesthesia before entering the machine, saving time and increasing scanner throughput for the hospital.

When device manufacturers don’t humanize the experience, users may do so themselves. While observing an elderly man with diabetes, I noticed that all of his supplies were in a Hello Kitty pencil box instead of the case designed to hold them. When I asked him about it, he explained that his granddaughter had given him the case to hold his supplies. When he pulled it out each day, he was reminded of why it was important to him to follow his diabetes protocol. The original case would have been more organized and functional, but it did not meet his social and emotional needs as well as the Hello Kitty case.

How Meeting Social and Emotional Needs Improves Device Effectiveness

In both of the examples above, humanizing the experience of using the medical device did more than make people feel better. It made the devices more effective. Children could get accurate CT scans without anesthesia. The man with diabetes was more likely to follow through with blood sugar testing when he was reminded of the reasons he wanted to stay healthy.

When the medical device fits into the user’s life, he or she is more likely to use it as intended. Patients are much more than the disease being treated. They are human beings with full lives, and they don’t always want to be reminded that they are “sick.” They also don’t want to be looked at differently by peers.

For medical device developers, that means thinking not only about a device’s functionality, but also its “softer” dimensions, like aesthetics. Consider assistive devices and prosthetics. Do they need to look so, well, medical? 3D printing has made it easy and affordable to design prosthetics that are customized to the user’s personal taste and personality, as well as to their physical needs. Children can have an “Iron Man”-inspired artificial limb that is the envy of the playground instead of a device that inspires pity or bullying. And how much more likely is a young woman to wear the hearing aids she needs when they look like cool jewelry that anyone might wear, rather than medical devices she needs because of a disability?

Aesthetics are important in non-wearable devices as well, such as nebulizers or home infusion pumps. A bulky, overtly medical device doesn’t fit well with home décor, and it invites questions — or perhaps unwanted sympathy — from visiting guests. A sleek, attractive device that blends into the home is more likely to be left out where it is more accessible when needed and may even be used more regularly.

Aesthetic considerations may seem minor when considering the important medical functions performed by these devices, but these concerns are not small to users. People who need to use medical devices want to think of themselves first as people, not just as patients. Acknowledging users’ social and emotional needs, and designing devices to address them, isn’t just “fluff.” It is essential to promoting effective device use and adherence to medical protocols.

The best way to do this is to consider the entire medical device “hierarchy of needs” right from the start, prior to device conceptualization. Contextual research can help manufacturers better understand all of users’ needs, from the physical and cognitive to the emotional and social. An integrated approach to device development that includes attention to social and emotional needs will result in devices that are better accepted by users and promote better health outcomes.

About The Author

Dr. Amy Schwartz is a Human Centric Design Thought Leader at Battelle and an Adjunct Professor at Northwestern University Segal Design Institute. She brings more than 30 years of experience in Human Centric Design with an emphasis on medical devices and healthcare.

[1] Maslow, A.H. (1943). "A theory of human motivation". Psychological Review. 50 (4): 370–96.