Small UV Plant Is Designed To Address Cultural And Safe Drinking Water Needs Cost-Effectively

By Deanne Mould, marketing coordinator, BI Pure Water (Canada) Inc.

BI Pure Water worked with University of British Columbia researchers and Lytton First Nation to develop a water disinfection system that addresses the needs of native communities, both cultural values as well as the basic necessity of clean drinking water. Many communities such as Nickeyeah in Lytton, BC are plagued by seasonal events — spring snowmelt and weather such as rainstorms causing turbidity and low quality water which triggers a large chlorine application.

“We believe many small communities have difficulties retaining trained operators or even have the equipment to deal with turbidity events,” says George Thorpe, BI Pure Water R&D Manager. BI Pure Water designs and builds custom treatment systems, and supplies systems and chlorine products and servicing to dozens of small communities across Western and northern Canada.

Lytton’s water maintenance manager, Jim Brown, concurs that too much chlorine is often the result. “We can’t continue to have these people living off the current system they have now with just chlorine as a disinfectant because of the high turbidity … the chlorine residual goes up so the people say they don’t like to drink the water because most of the time the chlorine residual is too high. Maybe that is one of the reasons they have sores or don’t feel very good after they have a bath,” says Jim Brown, water maintenance manager of Lytton First Nation recently in a CTV First Story news report.

People may also be concerned the chemicals alter the spiritual quality of the element, according to the CTV news report. They also have trouble adjusting to chlorine added to their source water when the community has been using it without for generations.

“Often in communities we realize if they have sufficient information and they know it is absolutely necessary to add a little bit of chlorine in their water they don’t have any objections,” says Madjid Mohensi, professor in the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering at UBC. “The objections to the chlorine comes when it’s too much chlorine and if it’s unnecessary addition of chlorine. So by collecting sufficient info from source of water and putting UV treatment as part of our treatment package we are minimizing the amount of chlorine that needs to be added,” says Mr. Mohensi.

The research team — RES’EAU-WaterNET — brought their mobile treatment plant to the Lytton community to begin testing the source water. Key to the success of the new treatment system for Dr. Mohensi and his team was determined to be community and operator input both before and during the design process. A previous system design by a consulting engineering company was rejected as too expensive, and the current chlorination system for this community and others is disliked. The operator, Jim Brown was instrumental in communicating the needs and goals of his community as well as his requirements as the manager and operator of the new treatment system. In return he knows the system inside and out, and who to call for any problems.

Jim Brown (second from right, Lytton water utilities manager, with some of the RES’EAU-WaterNET team testing inside the mobile plant.)

The RES’EAU Living Lab is a 20 foot cargo trailer with an operator-friendly, flexible water treatment pilot plant installed inside. Each treatment component has bypass piping to allow the use of specific technologies for each test. After a number of days of testing other treatment components can be added until the optimum process is determined.

The Living Lab has the advantage of selecting and testing specific components in real time to confirm that they are cost effective for the specific water source. Precise results can be obtained rather than an estimate of what the full plant might be able to treat. The size and cost of the full scale plant — often less than what must be estimated without full information — can be precisely determined when applying for municipal or federal financing. And most importantly, the community operator can work hands-on with the unit so that he/she feels confident of properly managing the full-scale plant.

Left to right: Bernadette Mah, program manager, Peter Wall Institute for Advanced Studies; George Thorpe, R&D manager, BI Pure Water and board member, RES’EAU-WaterNET; David Goertsen, research engineer; Dr. Madjid Mohseni, scientific director, RES’EAU-WaterNET; John Bergese, research engineer; and Ashish Mohan, manager of communications, IC-Impacts.

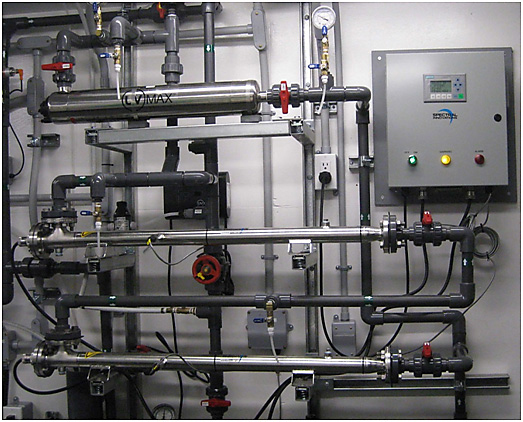

The permanent Lytton Nickeyeah water treatment plant is now under construction. The system utilizes a basket strainer to remove large particles and organic items that may be pumped from the creek and could plug valves or other components, a self-cleaning filter to reduce particles above 25 microns and some pathogens, a bag filter to remove contaminants down to 10 microns, a UV disinfection unit to neutralize bacteria, cysts and common viruses to required levels, and chlorine only as residual disinfection to remove microbiological buildup in the piping and remove any viruses left after UV disinfection.

The system, costing about half of a full plant, was approved last month for financing by UBC and Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC). The RES’EAU-WaterNET team hopes that this first pilot process will serve as a blueprint for all small communities across the country. The Living Lab will be hitting the road to the next small community within the next few weeks.

In this Living Lab, research is underway to determine how ultraviolet light and hydrogen peroxide (a form of advanced oxidation) can be utilized with small water flow rates to remove organics like tannins, harmful disinfection byproducts and personal care products that are common in many water supplies.

Today there are 1,238 boil water advisories across Canada, most in BC. Half of First Nations water systems in BC are deemed to be high risk; last year 20 percent of First Nations across Canada were forced to buy or boil their drinking water, according to CTV News.

RES’EAU-WaterNET is a cross-disciplinary research network devoted to finding innovative and affordable solutions for providing clean drinking water to small, rural and First Nations communities in Canada. Hosted by UBC, it is a 5 year program, funded from partnership with 24 public and private organizations and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC). The R&D team includes 22 world-class scientists from 9 universities across Canada, supported by more than 100 students and post-doctoral fellows. They collaborate across specific themes of investigation: 1) Innovative & Integrated Treatment Processes; 2) Water Health Assessment & Modeling; and 3) Governance, Risk Management & Compliance.