Meet The New Water, Same As The Old Water

By Kevin Westerling,

@KevinOnWater

As water-scarcity issues arise and traditional water sources dry up (sometimes literally), those in need will have to tap a new supply. The answer: clean up and reuse the same old water.

Follow an online discussion about water scarcity and you will invariably encounter the individual who informs you that we have the same amount of water on Earth that we have had for billions of years. That’s a true statement, but it misses the point. The issue is the lack of available water. Due to population growth, the water-energy nexus, and climate change, the replenishment of traditional sources — groundwater and surface water — is not keeping up with growing demand. We may not be able to control the weather (yet), but we can shorten the cycle for making water new again.

No one knows this better than Wade Miller, who has devoted more than 13 years to promoting the advancement of water-reuse strategies. Miller will soon retire (on March 31, 2014) as the executive director of the WateReuse Association and WateReuse Research Foundation, so I was fortunate to hear him speak recently at the 105th Annual Meeting of the Water and Wastewater Equipment Manufacturers Association (WWEMA). His presentation — the details of which are shared below — identified global and U.S. trends in water reuse, highlighting the fact that there is still much work to be done (especially domestically).

Why Is Water Scarce?

Miller called water scarcity “The new paradigm of the 21st century,” and identified the following drivers:

- Population growth

- The worldwide population is expected to increase from 7 billion (2012) to 9 billion by 2035, mostly living in megacities and developing areas.

- The water-energy nexus

- The energy sector accounts for 48 percent (195 BGD) of daily water withdrawals (408 BGD) in the U.S.

- By 2030, water consumption for electric power generation is projected to increase 50 to 150 percent in many high-growth, arid regions of the U.S.

- Climate change/extreme weather

- As the atmosphere warms, it holds more moisture (20 percent increase per ~5 degrees F)

- More intense floods and droughts (“wet wetter, dry drier” rule)

Where Does The U.S. Rank?

Of about 32 BGD of municipal wastewater effluent discharged in the U.S., roughly 7.3 percent is reclaimed and beneficially reused. By comparison:

- Israel reuses more than 70 percent.

- Singapore reuses 30 percent, up from 15 percent in recent years.

- Australia, now at 8 percent, has a national goal of 30 percent by 2015.

According to Miller, U.S. industry has begun to recognize the value of water, with corporate giants such as Coca-Cola, Pepsi, and Google likely to drive innovation in water reuse. Water is essential to nearly all industrial activity, Miller noted, citing food production, manufacturing, mining, and power generation as water-intensive sectors that can find the most direct benefit from recycling.

Municipal Reuse: IPR And DPR

On the municipal side, utilities in water-stressed regions will sooner or later be compelled to investigate water reuse, with two options: indirect potable reuse (IPR) or direct potable reuse (DPR). The latter — sometimes (and unfortunately) referred to as “toilet-to-tap” — is a tougher public sell. IPR, on the other hand, is reintroduced to the natural environment and goes back through the drinking water plant prior to distribution. Both approaches have their pros and cons, discussed here.

California, like many western U.S. states, is in desperate need of “new water,” and has officially committed to study IPR and DPR. In 2009, WateReuse California (WRCA) helped push through SB 918, which provides funding and deadlines for the California Department of Public Health (DPH) to complete regulations for IPR projects and to evaluate DPR. A report from DPH is due to the California legislature by 2016.

California Leading The Way

The WateReuse Association, in cooperation with the Association of California Water Agencies (ACWA), the California Association of Sanitation Agencies (CASA), and other water organizations, conducted a survey in October to gauge the state of water reuse among U.S. water agencies. Of the 208 respondents, 95 (45.7 percent) indicated that they are currently investing in recycled water projects, and 65 (68.4 percent) of those were from California.

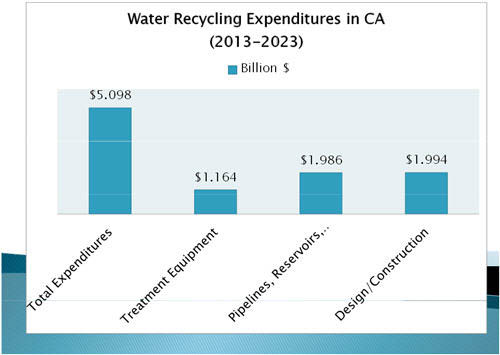

WateReuse staff concurrently requested financial data on the planned recycling projects from 15 major water agencies. The results (shown below) indicated a nearly $5.1 billion average total cost, which was broken down into three categories: 1.) treatment; 2.) pipelines, storage, pump stations, etc.; and 3.) design and construction.

Of course, cost effectiveness will by a deciding factor for many water projects. However, alternative options for water-scarce regions — desalination or transporting water from other areas — have their own drawbacks. Desalination may be a panacea (97 percent of the world’s water is saline), but it is less cost effective than water reuse in most cases. Piping in water from other areas is not only expensive, but ultimately unsustainable and sometimes contentious.

For now, water reuse seems to be a wise investment — and perhaps a mandatory one. After all, what’s the cost of not having water?